Latest News

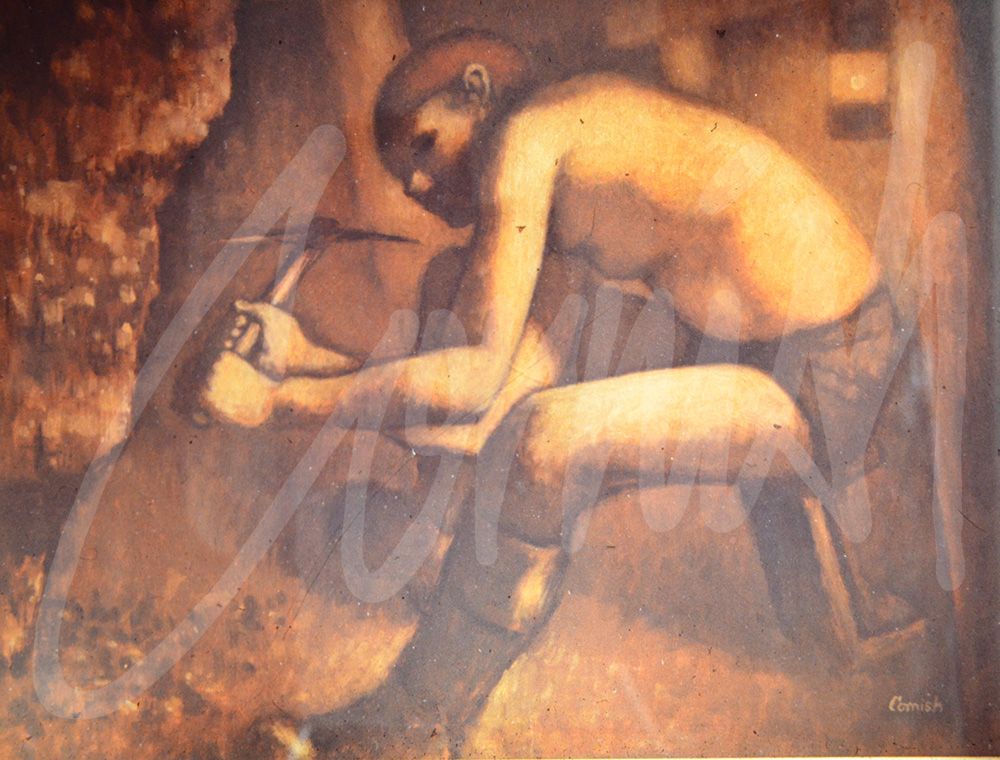

Industrial Gladiators:

Future generations may one day ask, ”what did coal mines look like and what did the men do underground?” The paintings of Norman Cornish have provided an honest and authentic illustration of life in the great pit villages and mining communities in County Durham. In his own words:

“ I didn’t think consciously about creating something that people would be able to look back on and say, ‘that’s what it was like’ but it must have been in the back of my mind: the thought that one day, someone could look back at my paintings and feel what it was like.”

The choice of the word feel is so incisive when viewing paintings by Cornish, whether it is the pit road, working underground, a pub scene or other observations of people and places. “If a painting carries nothing of life experiences it is sheer decoration.”

Cornish was ‘set on’ at Dean and Chapter Colliery to start on Boxing Day 1933 as a ‘datal lad.’ When he was 18 he was offered work as a ‘putter’ which meant a slight increase in his wages but the work was hard and dangerous. The job entailed conveying the full tubs of coal on rails from the coal face to the bottom of the pit shaft and leading empty tubs back to the coal face.

Eventually it became his turn to be a coal hewer; work which was done by hand, using a pick, shovel and drill along with a hammer and saw for installing props. Pay was related to the amount of coal produced and the work space was illuminated with the aid of an oil lamp – about one candle power!

At Dean and Chapter Colliery in 1935 there were 2,135 men working underground and 538 above ground and by 1937 the workforce was producing 3,000 tons of coal per day – a third of it machine mined and the rest hand hewn. The Dean and Chapter Colliery was referred to as ‘the Butcher’s Shop’ and on average there were six fatalities per year and minor injuries more frequently. The challenge for Cornish working underground was his desire to record what was happening around him whilst trying to continue the physically demanding work. The owners of the mines had no time for artists and aesthetics and it is simply remarkable that he was able to continue his output as an artist under such difficult conditions that he described as: ‘The dangers of gas, stone fall, the darkness and restricted space were all to shape these men into industrial gladiators.’