Latest News

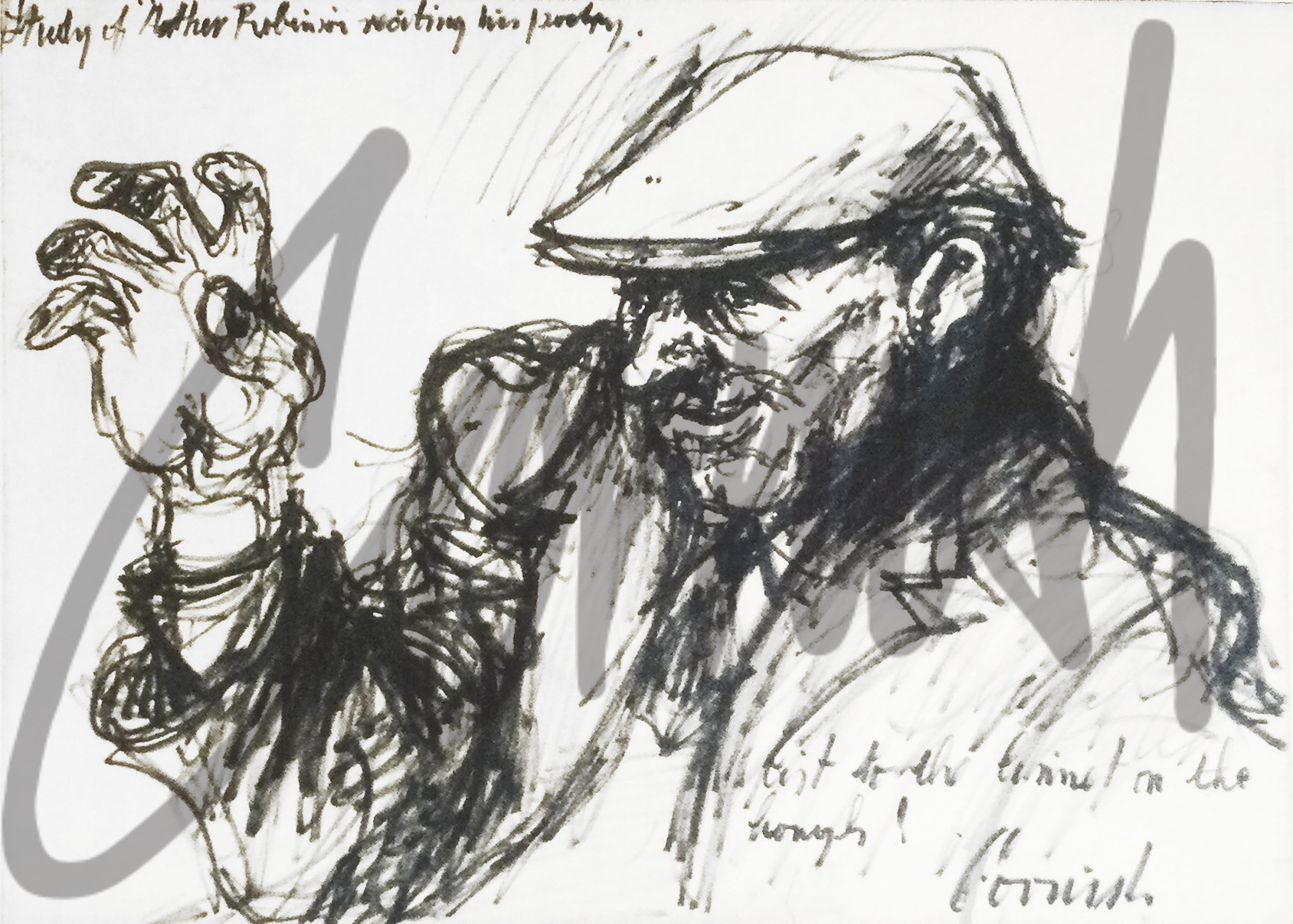

To a Linnet

List to the Linnet on the bough,

He sweetly sings for Spring is now,

He knows not of Einstein’s equations,

And nowt he cares for men’s relations.

Now list to our Geordie down the pit,

His hands are wet with baccy spit,

He knows his coal and stows his stone,

And whilst he toils he grunts and groans.

Now who’s the happiest bird or man?

Of brains and brawn the bird has none,

Yet he sweetly sings upon his bough,

Whilst Geordie delves in darkness now.

So sing, my songster, sing thy song,

‘Tis man, not thou who dost belong,

To a mad world of his own creation,

Whilst thou dost sing in jubilation,

Sing shy Linnet on the bough,

No songster can as sweet as thou,

Thou dost with charm and rapture rouse

The classic chords of music stir.

Sing shy Linnet on the dyke,

Thou singest now the song I like

Thou art the master of them all,

If I were blind I’d know thy call,

He who taught thee how to sing,

Of the song birds, made thou king.

Public Lectures 'Did you know?'

The programme of lectures about the life and work of Norman Cornish commenced about seven years ago following the launch of ‘Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks.’ In 2019 the series of lectures continued around the theme of ‘The Norman Cornish Centenary Lecture’ and the public appetite for these illustrated talks remains as strong as ever.

There are two distinct settings for lectures. Some take place for the members of societies and formal groups such as Local History Societies, U3A, Arts Groups, Women’s Institutes, Rotary Clubs, PROBUS and Friends of …… etc.

Public lectures are slightly different in that they are available for any member of the public and a nominal ticket fee is charged which also helps the organisers plan for the anticipated numbers arriving. Public lectures have also taken place at Art Galleries, Arts Centres, Town Halls, Book Festivals, The Lit & Phil and Redhills.

One of the unintended outcomes at all of these venues has been at the end of lectures when members of the public make contact to announce that they own a ‘Cornish,’ or know someone who does. A conversation often starts with ‘Did you know?,’ and without exception a whole range of fascinating anecdotes have been disclosed regarding Cornish, his work, his life, and historical relationships with other artists such as Sheila Fell, LS Lowry, John Peace and Ned Owen.

Several public lectures are currently being planned to support the Cornish/Lowry exhibition at the Bowes Museum from July 20th 2024 to January 19th 2025 and details will be published in the near future.

Meanwhile, ‘The Test of Time ‘ lecture will be at The Richmond Station Cinema on June 10th 2024 at 1-30pm . Tickets £4.50 via This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. or 01748 823062

Some accessible seating and parking is available at The Richmond Station Cinema.

In addition at the Richmond Station Gallery you can visit the latest exhibition of paintings and drawings by Ann Thornton (nee Cornish) ‘Form and Colour -Evolution’ The Artisan Gallery.

Mr Cornish & Mr Lowry: A Tale of Two Artists

When asked about the artist LS Lowry many people would most likely associate his work with his distinctive style of painting industrial landscapes with human figures often referred to as ‘matchstick men.’ However, there is much more to the life and work of Lowry, who eventually became one of the most famous 20th century British artists and was equally noted for his portraits, landscapes, seascapes and painting and drawing industrial towns in the North West. Often overlooked or unknown were his pictures from his time spent in the North East and South Wales.

There are few people in the North East who would fail to instantly recognise the work of Norman Cornish. His evocative paintings and drawings provide an unrivalled social record as a chronicler of an important era in English history. His observations of people and places are a window into a world which no longer exists outside but which Norman has immortalised for us all with its struggle, its beauty, its squalor and its dignity. As with so many things in life there is often more than first meets the eye and both Lowry and Cornish each shared a long and interesting journey to future success.

Laurence Stephen Lowry was born on the 1st of November 1887 in Barrett Street in Old Trafford, Manchester. Norman Stansfield Cornish was born on November 18th 1919, in Catherine Street in Spennymoor, County Durham. A chronological gap of thirty two years, but a much wider gulf in terms of their local environment and the socio-economic circumstances in which they both spent most of their early years growing up and as aspiring artists. Lowry’s family has been described as ‘lower middle class’ with parents who had high ambitions. The Cornish family was firmly rooted in working class culture with an underlying basic need to survive ‘hard times.’ Lowry lived for 88 years until 1976 and Cornish ‘passed away’ in 2014 at the age of 95.

Cornish lived in a house with no bathroom or inside toilet, where he shared a room with his five brothers and one sister. He described living conditions as ‘primitive’ and he contracted diphtheria when seven years old. The only reading material at home was an American detective comic. His journey from miner to professional artist is a story of determination and resilience to overcome hardship and prejudice.

In his early years Lowry suffered repression from his mother, an accomplished pianist, who was disappointed when he was born, hoping for a girl. She was also frustrated that he didn’t share her aspirations for a traditional academic route to future employment in view of the investment his parents had made for Lowry to attend a private school. Lowry’s emerging interest in drawing was met with chagrin within the family circle although he was determined to fulfil his interest in drawing and painting. Lowry was the only child of an apparently loveless marriage and a weak and unsuccessful father who died in 1932.

Cornish started work aged 14 years on Boxing Day 1933 at Dean & Chapter Colliery. He walked three miles to work in the snow to start as a Pony Putter. He was denied the opportunity of continuing his education like so many others at this time.

Lowry’s parents appeared to show a lack of interest in his progress at school and he also had little talent for music. They had their own ideas for his future direction and career but he began to develop a desire to draw which became useful to fill his time and which absorbed him in his lonely hours at home. His extended family rather than his parents began to notice his interest in drawing as they recalled his sketches of boats and seascapes on scraps of paper from visits to the coast. His father occasionally took him to visit the Manchester City Art Gallery.

Mr Cornish & Mr Lowry: A Tale of Two Artists Part 2

Both artists were influenced by their immediate environments. One day in 1916, Lowry missed his train to art school, but the view from the station steps became significant when he saw the yellow lights from the Acme Mills. His vision to paint the industrial scene was born, and he claimed "nobody had done it," although this was not entirely correct. For example, Dowlais Iron Works (1840) in South Wales and paintings by Joseph Wright of Derby in the 18th century.

Lowry was initially rejected by the Manchester Municipal College of Art, but a family friend, Reginald Barber from the local Sunday School, was Vice Principal of the Manchester Academy of Fine Art, and he said, "send the lad to me." Lowry attended three different art schools while working as a rent collector. One of his tutors was the French Impressionist Adolphe Valette, who became a huge influence. Lowry also experimented with the evolution of his figures, and Professor Millard suggested that "they all look like Marionettes and if you pulled the strings they would all cock their legs up." This observation appealed to Lowry and contributed to the evolution of his figures to become "people as automatons." He was later advised to use a white background to make buildings and people "stand out." He developed a characteristic style to suit the industrial and city subjects that he generally painted with a limited palette of five colors: ivory black, vermillion, Prussian blue, yellow ochre, and flake white. According to Lowry, he generally "invented the figures" in his pictures.

For the first thirty years of his life, his work was ignored, and in his twenties, when he painted some of his most famous pictures, he was often ridiculed as a "Sunday painter." He didn’t sell much of his work. In 1930, Lowry staged a solo exhibition of drawings at The Roundhouse, Manchester University Settlement, which was also part of the national Settlement movement.

Cornish was initially turned away from The Spennymoor Settlement Sketching Club because he was too young. He eventually joined and was influenced by the advice to "paint the things around you." He was denied an opportunity to attend The Slade School of Art because it was 1939, and he was in a "reserved occupation" and had to continue working as a miner. The members of the Sketching Club were gifted a set of oil paints by Mrs. Baker-Baker of Ellemore Hall, and Cornish also used pastels, charcoal, watercolors, and, from the early ’50s, a Flo-master pen as his career developed. Cornish's sketchbooks contain hundreds of observations of people in different settings who often appear later in different compositions. A selection of Cornish’s sketchbooks will be featured at the forthcoming Cornish/Lowry exhibition opening on July 20th, 2024, at The Bowes Museum.

The Spennymoor Settlement was hugely influential on Cornish's development as an artist when he joined "The Sketching Club." This "cradle of creativity" was also the stepping stone for other members such as Sid Chaplin OBE, Tom McGuinness, and Arnold Hadwin OBE. The members were steeped in landscape tradition, but without a doubt, the most significant influence on his development was Rembrandt. Like Rembrandt, he produced a series of self-portraits, but he was also fascinated by Rembrandt’s attention to the humble and mundane activities of everyday life. An early Cornish landscape study is included today alongside a similar piece by Rembrandt from 1650. After working underground, Cornish compared going to the Settlement to "stepping inside a warm woollen sock."

Mr Cornish & Mr Lowry: A Manchester painter called Lowry

His mother, who saw no beauty in his pictures, said, "Nobody wants pictures like this." His fellow students, who did not understand them, said it. The public, with their refusal to buy them, said it. Local councillors, regarding them "as insults to the people of Lancashire," said it. The Manchester Academy of Fine Arts laughed at Lowry, but his vision was distilled and its sharpness captured in his mind’s eye, and he became fascinated and totally absorbed by it.

In 1930, Lowry was invited to illustrate "A Cotswold Book" (his only commission). This was a golden opportunity for Lowry to create a positive impression with the publisher, describing himself in glowing terms, recent invitations to exhibit his work, and a recently completed Self-Portrait—featured today.

In 1933, Lowry exhibited with the Royal Society of British Artists, and an article published in the Manchester Evening News disclosed his full-time job as a rent collector. This caused an outrage, and from this time onwards, he studiously kept secret the nature of his job, which was only revealed at his funeral in 1976.

Lowry's father died of pneumonia in 1932. His mother became bedfast for the next seven years and completely ruled his life until she died in 1939 without knowing his imminent success. For nearly thirty years, from 1910 to 1939, when he had a first London exhibition, he painted without recognition, with a single-minded determination that enabled him to cope with repeated rejection. A breakthrough occurred as Lowry was approaching his fiftieth birthday when a director of the exclusive Lefevre Gallery visited the frame-makers James Bourlet in London and spotted one of his pictures carefully placed on a chair. The visitor asked about the artist, and the reply from Daisy Jewell, an old friend of Lowry and Director of Oldham Gallery: "Oh, he’s a Manchester painter called Lowry. We’ve been sending his pictures to exhibitions for years but they always come back unsold."

The young Cornish became exposed to the significant expertise and experience amongst the members of the Sketching Club. He was "taken under the wing" of Bert Dees, who had exhibited at the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle, and whose brother John Arthur Dees had studied at the Gateshead School of Art and had exhibited at the Royal Academy. Bob Heslop had studied the art of screen printing under the guidance of teachers at the Guildford School of Art, and later the members were joined by Elisabeth Countess von Schulenberg (Tisa Hess) for two years. She had been a sculptor at the Berlin Academy prior to fleeing Nazi Germany. The members may have lacked formal art tuition, but they had access to the public library, which was based at the Settlement. Annual exhibitions were a notable feature of the Settlement, and visitors arrived from all over the British Isles. In 1939, Cornish was singled out for particular note, and his portrait of his grandmother was of exceptional quality. His drawings were later described by Andrew Festing (Former President of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters) "as good as any other artist in history."

The Settlement provided many enriching experiences for the members, and the theatre became a venue for touring theatre companies, including The Old Vic performing "The Merchant of Venice" during World War 2. The Settlement and its activities are historically important for the talent nurtured and mutual support provided during challenging times. Four of the members went on to receive national and international acclaim: Norman Cornish MBE, Sid Chaplin OBE, Arnold Hadwin OBE, and Tom McGuinness.

Following the death of his mother, Lowry was distraught, bereft, exhausted, and adrift. He was soon advised by his doctor to take a break for the sake of his own health, and because he always enjoyed the seaside and had visited the area previously, Berwick was an obvious choice. He locked his mother’s bedroom for 12 months and later completed the picture featured today. To be continued...

More Articles...

- Lowry in the North East

- The Sailors’ Bethel

- The Stone Gallery Years

- A New Era

- Mr Cornish and Mr Lowry: Together Again

- Norman Cornish, Spike Milligan and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

- The Durham Book Festival

- ‘The Test of Time:’ A new book about the life and work of Norman Cornish

- The Test of Time

- Hanging on the Walls