Latest News

The Local Collieries

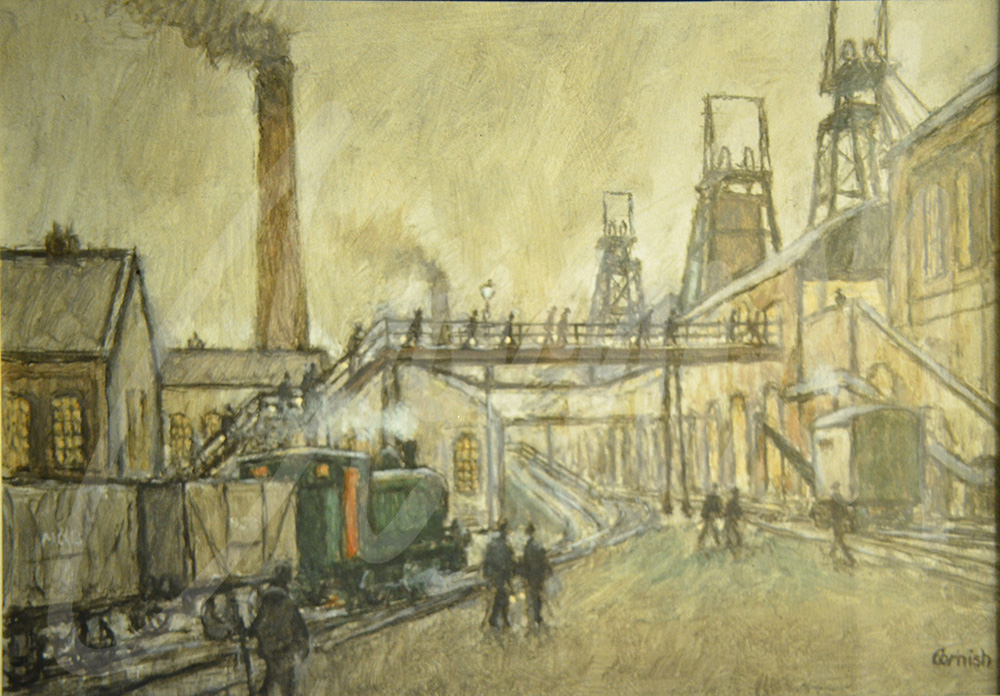

In 1919, the year of Cornish’s birth, there were a million coal miners in Great Britain. Almost a quarter of them, some 223,000, worked in the North East of England. In County Durham a large percentage of the workforce was employed directly in mining and related industries. Mining, with its pit heaps, pit head gear and rows of mining cottages, dominated the physical and mental landscape of the county. Within a five miles radius of Dean and Chapter Colliery there were over a 135 ‘collieries and pits,’ including brickworks, quarries and coking plants at varying times.

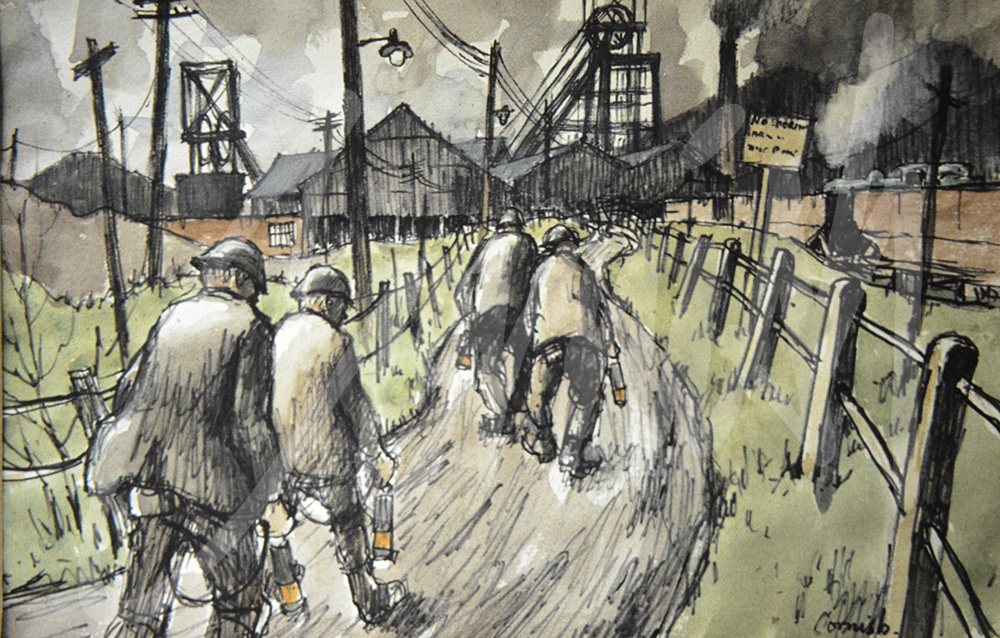

It was hardly surprising that the immediate environment was to make a crucial impact on his early responses as an artist. The smoke and sounds of the railway engines hissing, coal trucks, colliery buzzers, miners’ boots on the gantry steps and the daily ‘knockers up’ combined to create an industrial cacophony. The impact upon the environment and the men was pervasive.

Cornish started work at Dean and Chapter Colliery on Boxing Day 1933, aged 14, where there were 2,135 men and boys working underground and 538 working above ground. By 1937 the workforce was producing 3,000 tons of coal per day- a third of it machine mined and the rest hand hewn. The pit was referred to as ‘the Butcher’s shop’ and accidents, including fatalities, were frequent.

He worked at the Dean and Chapter colliery until 1962 when he was transferred to Mainsforth where he was commissioned by Durham County Council to paint the mural for the new County Hall. He was later transferred to Tudhoe Mill Drift (whose banner he had designed), a much safer pit where he worked for two and a half years. Cornish’s final pit was Tudhoe Park Drift where conditions were very wet and his increasing lower back pain from working underground for over thirty years was the final straw!

Following persuasion from his wife Sarah, and constant pressure from the owners of the Stone Gallery in Newcastle, he decided to become a full time professional artist. To associate Cornish exclusively with his depiction of life in mining communities devalues his vast skill and achievements as a leading artist of the 20th century whose work may be found in public and private collections throughout the UK and beyond.

In the early days of his career as an artist there was an inevitability that the pits where he worked and some others in the surrounding area would eventually feature as part of the social record of his life and times.