Latest News

Sarah Cornish: ‘Hold it there’

Cornish’s evocative paintings and drawings provide an unrivalled social record, chronicling an important era in English history. His observations of people and places are a window into a world which no longer exists outside but which Cornish has immortalised for us all with its struggle, its beauty, its squalor and its dignity.

In a recorded conversation during 2007, Cornish was asked if there were particular pieces of his work which he regarded as personal favourites. He suggested five examples, beginning with his studies of his wife Sarah, acknowledging the huge contribution she made to his success and loyal dedication to their family and home.

They met one weekend in 1944 at a dance at the Clarence Ballroom in Spennymoor and two years later the couple were married at Rose Street Methodist chapel in Trimdon Grange. The newly- weds lived in with Cornish’s paternal grandmother and conditions were far from ideal with an earth closet and no hot water. There was no room for Cornish to paint, although the Spennymoor Settlement was a short distance away. Norman and Sarah eventually moved to 33 Bishops Close Street in 1953 following several years of temporary accommodation.

Towards the end of his career in mining, Cornish suffered lower back problems; he was anxious about leaving the colliery and the relative security of a modest income and family home. Sarah insisted that if he didn’t put his notice in then she would! The move to 67 Whitworth Terrace soon followed in 1967 enabling Cornish to work in a suitable environment to develop as a professional artist.

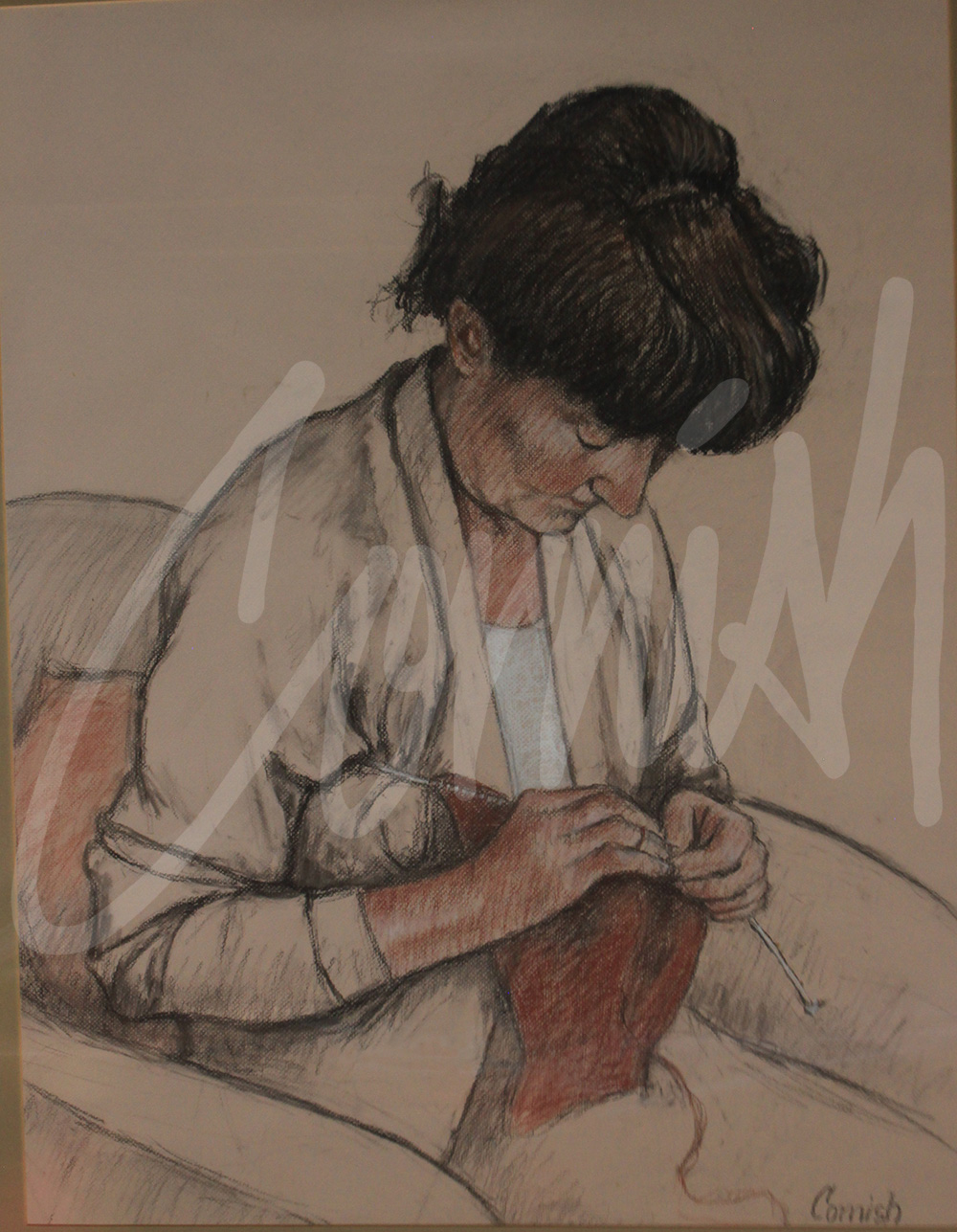

Sarah Cornish provided the stability and continuing support essential for her husband to develop his career. Her quiet nature belied her inner strength, patience and calming demeanour which was essential for Cornish to concentrate on his work and future success. She was also the subject of many drawings and paintings throughout her life. Often while working and sometimes in more formal poses. ‘Don’t move’ and ‘hold it there’ became the signal to pose for Cornish in all sorts of fascinating domestic situations which would be typical of the experiences of so many women in this particular piece of social history.

“I many times drew and painted pictures of my wife Sarah, when she was busy with household chores, especially when she was knitting. I felt her prayer-like attitude gave the pose of sanctity and her knitting was her way of praying, really, doing her best to keep our home and children together. This portrait represents a pose which was typical of thousands of women who were heroines of the coalfield.”