Latest News

The Crowded Bar

The Crowded Bar was discovered in February 2014, a canvas rolled up, at the back of a wardrobe in Whitworth Terrace at Spennymoor. Norman and Sarah Cornish had transferred to residential care and tidying the house revealed three previously unseen canvasses,

Cornish returned to the theme of the pub throughout his career. Bar scenes with individual character drawings, men playing dominoes, convivial conversations, and drawings of darts players. He also made detailed drawings of the beer pumps, furnishings, pint glasses and posters to ensure accuracy in his work. These features sometimes appear as individual component pictures because of their own special qualities and occasionally they are brought together in large composite paintings. Most of Cornish’s larger works involving many characters are constructed in this manner.

The Man at Bar with Dog illustrates the development of what appears to be a simple idea but one which becomes part of an evolving series. The true significance emerges when the series is considered as a continuum of development as individual characters may be tracked through various interpretations. The initial idea may have been drawn insitu but then ‘worked up’ towards a perfect composition. The Crowded Bar is a classic example of this approach.

In his own words:

About 40 years ago I would visit a great many pubs as they were marvellous places to practice drawing. I remember that in this particular scene, I must have made many drawings. I liked the attitude of the figures and also the big round lights. I remember sitting on a seat and surveying this scene. I have tried to paint it just as it was. I was fascinated by the men standing at the bar drinking and talking, or sitting playing dominoes.

The large oil paintings such as The Crowded Bar, have carefully constructed compositions’ incorporating characters and details from his extensive collection of sketchbooks. These drawings enable Cornish to create informal conversation pieces where a group of people appear to be interacting naturally.

The subject of Bar Scenes is covered in detail within Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks, including a number of previously unseen preparatory drawings and sketches . Reference to this subject is also covered in two of the four essays by distinguished authors and historians Dr. Keith Wilson, Dr. Robert McManners and Gillian Wales (Cornish’s Biographers).

Norman Cornish Anthology

The anthology represents a creative response to Norman’s artwork which was exhibited across six different galleries in the region, with workshop sessions involving over 3000 participants as part of a community engagement programme.

Influenced and inspired by Norman’s life and work, the poetry workshops (led by poet Tony Gadd) provided a creative outlet for people to express their responses to the artist’s paintings.

Norman had a deep, emotional attachment to his community; he hoped his work would be important enough to make people look at themselves and reflect upon how they feel. The poetry workshops afforded people an opportunity to express feelings and demonstrate that personal connection.

An interactive preview of the anthology is below, or click here to download it in PDF format.

Bishops Close Street

Cornish lived in Bishops Close Street, Spennymoor, for most of his childhood, moving there when only a few months old from nearby Oxford Street.

During his youth, the housing conditions on the street were primitive; there were no bathrooms, gardens or inside lavatories. The houses were illuminated by gaslight and a penny gas-meter. Epidemics of diphtheria, smallpox and scarlet fever were rife amongst the children.

Bishops Close Street was surrounded by the old ironworks, the gas works and the railway line - a harsh industrial landscape. But as Cornish later recounted, ‘to live next to a large slagheap mightn’t sound very pleasant, but to our inventive young minds it became an adventure playground’.

After marrying Sarah in 1946, and living first in rented rooms, the couple moved to their own house on nearby Catherine Street in which Cornish’s grandmother had once lived. In 1953 they returned to Bishops Close Street, to a Colliery house that was better equipped and more suited to family life after the arrival of their children, Ann and John. Here Cornish recorded the everyday life of his family in hundreds of deeply personal sketches. Cornish rarely dated his work but the scene captured at the back of the street suggests the late 1950s, showing a piece of social history as a delivery of coal was being shovelled into the coal shed. The young girl in the painting may be Cornish’s daughter Ann, providing a contrast to the gloom and remnants of industry, with the shape of the plume of smoke repeated along the washing line.

The street was also a busy through-route for people walking to and from the factories at Low Spennymoor, and Dean and Chapter Colliery at Ferryhill via the bridge under the railway line at the end of the street.

The family remained in Bishops Close Street until 1967. The mines were closing, and more space was needed both for the growing family and for Cornish’s development as a professional artist. The move was made to Whitworth Terrace.

In his own words:

’I think of houses I once lived in, that I grew up in, that my early married life was spent in and that my children were born in, but they are all now gone. Indeed, the site of my last home in Bishop’s Close Street is now occupied by swimming baths’

33 Bishops Close Street is being recreated at Beamish Museum as part of the re-making Beamish 1950s town and is featured in Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks with previously unseen images.

I Remember : A Palette of Words

Tony Gadd was ‘poet in residence’ throughout the Norman Cornish Centenary. Later this month an Anthology of works created during the Centenary workshops at each of the exhibition venues will be published via this website. Participants will be receiving personal copies in due course.

Poetry is a powerful medium which also has the capacity to evoke memories and trigger emotions. Many people have a favourite poem.

I Remember (title) takes the reader on a journey through Tony’s early years and is a constantly evolving poem initially inspired by Cornish’s paintings and drawings. It was warmly received as an introduction at a number of Centenary lectures, and is published here for the first time. Tony has personally selected the images to accompany this poem in recognition of the inspiration they provided.

Tony plans to publish his personal Anthology in the near future and it seemed appropriate to share his palette of words as a taster of things to come.

If you would like to contact Tony directly about his work and receive details about any forthcoming publications, then he may be contacted at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

I REMEMBER

I remember Colour TV in the 1960s laid on the floor, elbows on cushion, chin on hand s watching Stingray, Captain Scarlet, Thunderbirds and Joe 90 fantastical tales, all filmed in ‘Supermarionation’

I remember Swooning and cooing over Aqua Marina a mute, tail-less mermaid with Bridgette Bardot lips and silicon polished eyes

I remember Wondering if she would ever choose me over Troy wondering what the hell was ‘Supermarionation’ ?

I remember Thinking all baddies had thick necks, shiny bald heads with thick bushy eyebrows over menacing eyes and devilish grins

I remember Sitting in the barbers shop with me Granda I screamed as the barber set fire to a mans head watched as he then waxed and polished it brushed the collar of his ever expanding neck transfixed, my eyes bulged as he turned and smiled

I remember Running out the barbers, thinking me Granda must be a real gangster as he new lots of baddies

I remember Me mam typing quicker than I could speak writing in hieroglyphics, she said it was ‘short hand’, but it looked pretty long to me

I remember Going to the Odeon cinema in 1969, aged 7, to see me first ever film, 2001 A Space Odyssey two and a half hours of my life i’d never get back wondering what the hell was it all about hypnotic visuals, discordant sounds, assaulting my senses few words, lots of space, space, space and no ending

I remember Months later being nonplussed, as Apollo 11 landed on the moon all black, white and grainy, no invisible ‘HAL’ to talk me through it

I remember Fifty years later realising, why the 7 year old me didn’t get it with its themes of existentialism, human evolution, AI, and extra terrestrial life, still not sure I get it now, still never watched that film again

I remember Getting drunk on cadburys old Jamaica chocolate, 9 pence for a 3 and 3/8 ounce bar a burnt orange sleeve, with gold foil cover feasting square by square on a pirates treasure, followed by a palate cleanser of 2 hubbly bubbly or some golden nugget chut

I remember Tripe, liver and onions, leek suet pudding boiled in a cloth, penacalty, fish finger stotties, bacon grill and pressed ox tongue in a pyrex bowl, which doubled up on Sundays for a 10 bob swirl of Mr Whippy. ice cream. Beef’n’drippin, spam fritters, faggots in gravy, fray bentos pies, and a spare key kept in a draw just in case, to open tins of corned beef

I remember Sunday lunches, huge roast joints that would last all week Yorkshire puddings the size of your plate pressure cooker veg fresh from the allotment all doused in grandmas secret recipe mint sauce skin on rice pudding served out of huge enamel tins all cooked in Council Rayburn, the commoners AGA

I remember Scraping the ice off the inside of me metal framed single glazed window, to see if it had snowed overnight, then dressing in front of the open fire, the only heating we ever had Then shovelling snow to get out of the house, to get to school, which never, ever, ever, shut for the weather

I remember Frozen wet feet from ill fitting rubber wellies soggy woollen mittens, strung through duffel coat arms the tingle in finger and toe tips as they quickly began to thaw much like the coal dust speckled snowman i’d spent hours creating

I remember The smell of rubber plimmies, hanging in bags from cloakroom hooks doing PE in my pants and vest and those slip on jabs or sand shoes third of a pint bottles of milk served at school morning breaks prunes and custard, discarded stones balanced on edges of bowls ‘Tinker, tailor, soldier, sailor’ ringing out around the hall those who reached thief often missed afternoon classes spending their time instead on the bog

I remember School days, playing ‘spot’ with a brown leather casey against crumbling sandstone outside bog walls adjacent allotments with owld gadgees in diamond patterned cardies, who pass freshly picked tomatoes from grubby hands, through diamond patterned fence, halved with a penknife used for grafting plants, whittling stakes and sharpening stubby pencils, just big enough to fit a’hind their ever growing lugs

I remember Drawing the short straw and being sent in to buy beer, under age, at the off-sales window of the Colpitts Pub, two bottles of Samuel Smiths bitter all we could afford, shared between ten, more spit than beer, how bitter sweet it was

I remember Coal fired chippy’s serving up, fish lots, dab and chips, and a bag of scraps or scrapings’ wrapped in yesterdays newsprint, nee forks, fingers arnly, discount given for yesterdays news

I remember Using my great grandfathers shoe last, to feed the soul Sutton Street cobbler with kiwi polish and buffed leather smells provides horseshoe heels, a pound of blakey rounds and quarter tip segs to feed the soles, to stamp my feet, to make some noise to parade, drill and pass out

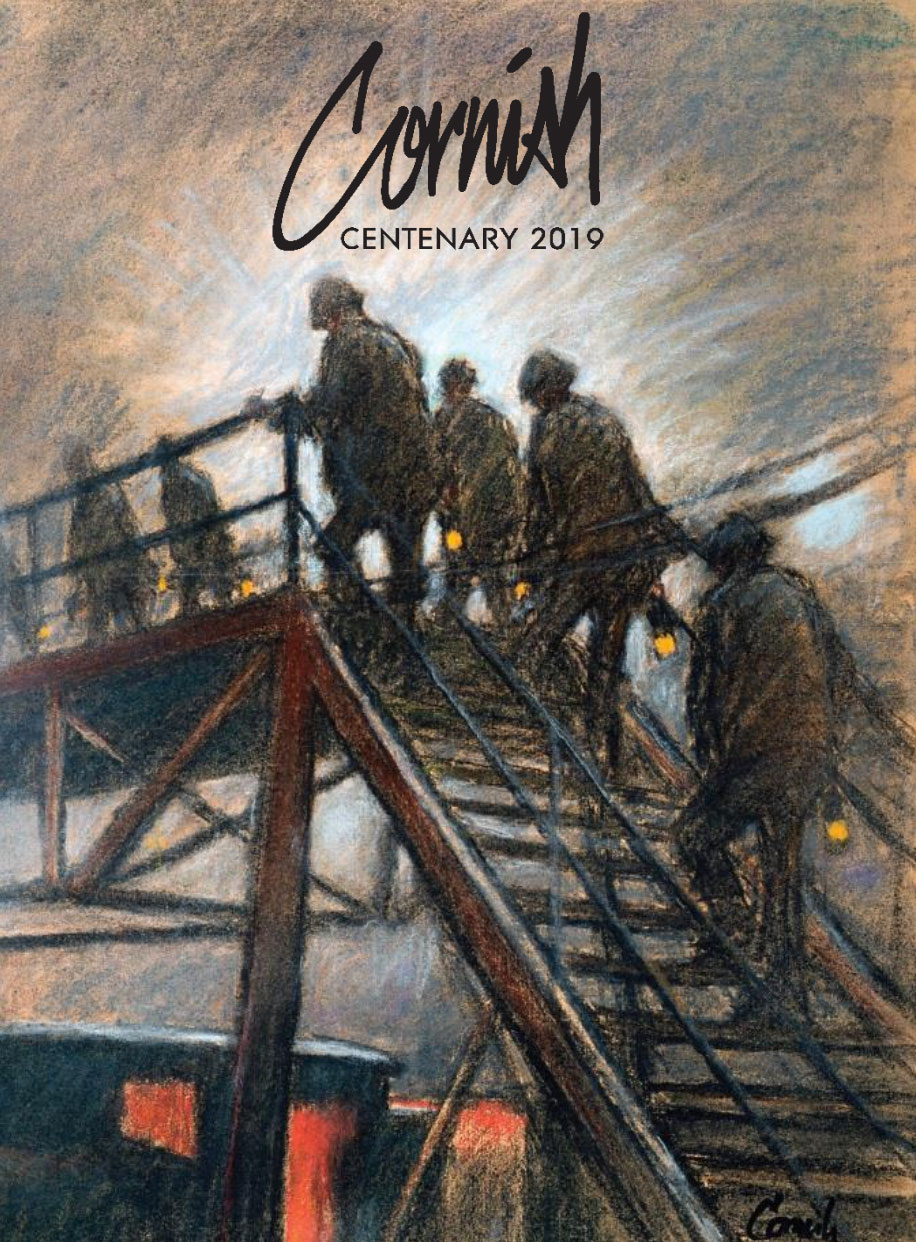

I remember Pit heap, pit head, pit wheel and gantry landscapes Huge pylons, aerial tubs and telegraph pole skylines, The smell and taste of an autumn days smog, and the phosphorus orange glow from the pit yard lights.

I remember Coal deliveries, dropped in back lanes, menfolk still on shift, women at h’ame left to handball frem lane to shed on return frem shift, the pitmen diarise, the quality of load delivered

I remember Pitmen tewing the’ pluck oot, blue tattoos, chiseled into hands and face scars hewn from years spent at the seam, flat cap, hides many more tokens, from time underground as they speak, the only thing visible, butt ends of broken, rotten teeth

I remember Them haakin’ an coughin’ the black spit up deep roond pullie eyes, hide any notion of emotion, foot-rot ’n gout, huge spots all ower the feet and hands burnt off by blue lotion issued from the infirmary stag, frem lack of light, isolate them frem life ootside ralloused, with caisson disease, dust, and anthracosis, pneumo and skumfish, all of them explained away as bronchitis have em all at h’ame, reaching for oxygen, hauled roond, on a cast iron trolley

I remember The first time seeing Norman Cornish’s paintings browt a tear to me eye, as I saw aa’l me family that had gone befower aa’l the memories of that life lang gone. now I use a palette of words to explain our heritage, our community. our hopes for the future, our destiny, our ‘ Slice of Life’, our ‘Sense of Place’, in this landscape, we call h’ame

Eddy’s Fish Shop

Eddy’s Fish Shop, now demolished, was a focal point in the community. This was from a time when ‘corner shops’ were a common feature in many towns and villages.

Cornish’s interest in Eddy’s Fish Shop began one day in the early 60s when he called to see Stan and Mary Eddy in their shop and he asked the question:

‘Stan, do you mind if I paint your fish shop?’

Stan and Mary Eddy originally owned fish and chip shops in Church Street and Villiers Street and there were other fish and chip shops in the town. Mary and Stan met in the RAF where Mary was a truck driver and Stan had returned from living in the USA. During a period of change in Spennymoor, the fish shop at the bottom of Craddock Street became available as Stan’s brother Oswald approached retirement. The shop was surrounded by houses, pubs and The Rink Ballroom (formerly The Clarence Ballroom) where Norman first met Sarah in 1944 . Oswald’s initial was retained on the sign outside and the location was perfect for brisk trade. It also interested Cornish who saw the potential for a scene which was to become one of his most admired subjects, evoking memories for so many people who grew up at a time when fish and chip shops featured with significance in communities.

The shop remained open until circa 1974 when it was demolished along with the ballroom and other unsafe buildings. The paintings and drawings are all about community and a particular slice of life. Stan and Mary’s sons became popular stalwarts in the community - Ronnie as Chair of Governors at Rosa Street School, (located a short distance from the shop) and Gordon who served with distinction as a member of the Durham Constabulary for thirty years.

In his own words:

The local collieries have gone, together with the pit road. Many of the old streets. chapels and pubs are no more. A large number of the ordinary but fascinating people who frequented these places are gone. However, in my memory, and I hope in my drawings, they live on. I simply close my eyes and they all spring to life.

The final word from Ronnie Eddy:

‘The chips were regarded as good, but couldn’t touch the chip van!’

Eddy’s Fish Shop is featured in Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks, and the original location in Craddock Street may be visited as part of the Norman Cornish Trail. normancornish.com/trail