Latest News

A Portrait Artist

For Norman Cornish the 1970s was a period of both consolidation and development as an artist with his studio enabling him to become completely absorbed in his work, without distractions. Not even a telephone in the house.

His paintings and drawings increasingly received national acclaim on many fronts. A second purchase of a Cornish painting by the Prime Minister Edward Heath, gave him some quiet satisfaction that his work was heading for number 10. However, Cornish declined a photo opportunity with the PM at The Stone Gallery alongside LS Lowry, Sheila Fell and his agent Mick Marshall. The photographer was the film producer Brian Forbes.

During this era, Cornish appeared in three different television documentaries for the BBC and Tyne Tees TV. A radio broadcast followed with Melvyn Bragg, who made his first TV documentary in 1963 for BBC - Two Border Artists: Norman Cornish and Sheila Fell. An Honorary Master of Arts degree was awarded to Cornish from Newcastle University and one of his self-portraits was also photographed for the National Portrait Gallery.

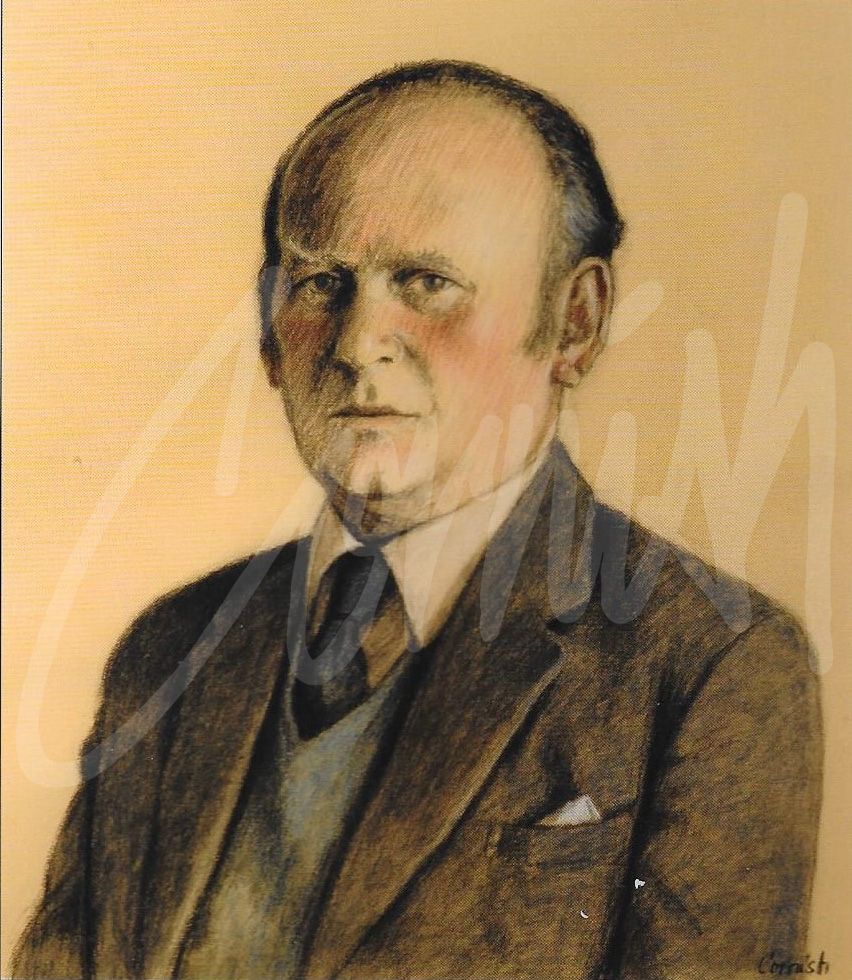

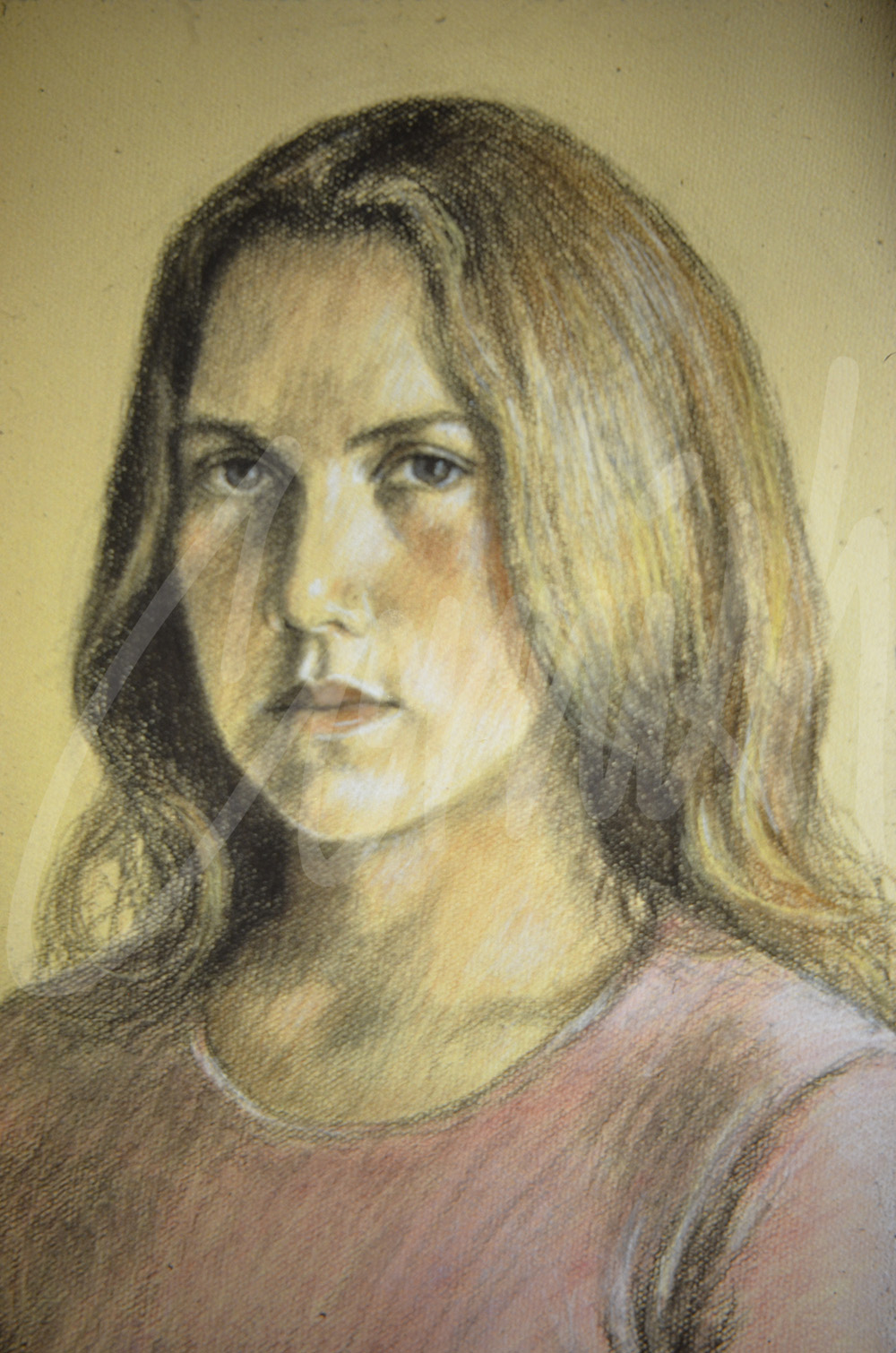

In between this close attention and rising profile, Cornish received a number of commissions, including a request to paint the portrait of Viscount Mathew Ridley. Cornish’s large studio was arranged with a table in the centre with table legs specifically reduced to a height of 50 cms. The sitter stepped up, sat down on a chair, and was immediately at eye level with the artist for a number of sittings until completion of the portrait.

Cornish was aware of the importance of this commission because of Lord Ridley’s art connections. His wife’s grandfather was Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens, Fellow of The Royal Academy and member of The Royal Fine Arts Commission. Lutyens was the designer of the Whitehall Cenotaph and he had been named after a friend of his father’s, the famous Victorian animal and portrait artist, Sir Edwin Landseer who is probably best known for his huge bronze lions in Trafalgar Square and his depiction of The Monarch of The Glen.

Norman and Sarah Cornish enjoyed a very good relationship with Viscount Mathew Ridley who was delighted with his portrait .

Viscount Mathew Ridley Pastel

A Man of Destiny : Interesting Times

In 1945 at the age of 26 Cornish made an important aspirational statement published in the newsletter of a national organisation.

‘Art this study that gives us so much pleasure, is worthy of study and personally I consider it worthy of the study of my whole lifetime.’

Despite having to continue working underground as a miner he began to make progress along the path to public exposure of his work, but also a growing recognition through sheer determination and resilience. These steps took him beyond the ‘Sketching Club’ exhibitions along a trajectory as a participant in exhibitions of huge significance in his development as an emerging artist of extraordinary ability. His first solo exhibition in 1946 at the Green Room, the People’s Theatre, Newcastle, was followed in London with ‘Art by the Miner’1947, including a first BBC TV appearance. In 1950 ‘The Coal Miners’ exhibition at the Artists International Association Gallery in Leicester Square continued the upward spiral of engagement and wider recognition.

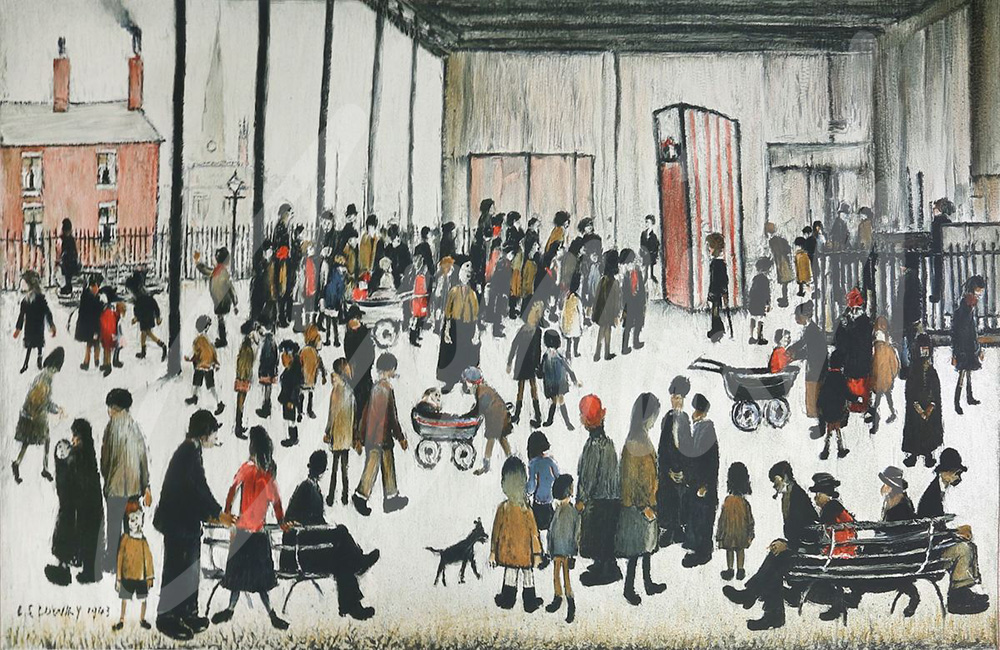

More exhibitions were to follow and one of particular prominence in the north of England was planned in 1951 at Tullie House, Carlisle: ‘Realism in Contemporary Painting,’ by Northern Artists. The exhibition was organised by Cumbrian artist Norman Alford supported by Bob Forrester. Together they went to extraordinary lengths to highlight music and art in Cumbria with which the ‘ordinary man’ could engage. The underlying principle in the selection of artists and their work was that they should portray everyday life from their own specific locality: Social Realism. The other invited artists included; LS Lowry ‘The Punch and Judy Show,’ Norman Cornish ‘The Fish Shop,’ along with works by Ned Owens and Theodore Major.

Victor Pasmore, Head of Art at Newcastle University was a guest artist who wrote the catalogue introduction despite his modernist style which later proved controversial with his Apollo Pavillion structure in Peterlee in County Durham. During this post-war era other artists and art schools were creating a tension as they steered students towards ‘fashionable tricks’ and experimentation. One of Cornish’s contemporaries in the late 50s and early 60s disclosed that he had been ostracized at Leeds College of Art by tutors who were keen to embrace the modern art movement despite his love of a traditional approach to landscape and portraiture.

The Tullie House exhibition marked the beginning of a period of 16 years where Cornish and Lowry exhibited together, continuing in 1952, ‘The Mirror and The Square,’ New Barrington Galleries, London, and thereafter at The Stone Gallery in Newcastle where they shared the same agent. Cornish also returned on several occasions to The Borders Arts Society in Carlisle, during the mid- 60s to address the members about his work. The paintings of the original artists who exhibited in ‘Realism in Contemporary Painting’ have also stood the test of time and may be viewed via a simple search of the internet.

The Perfect Pint:

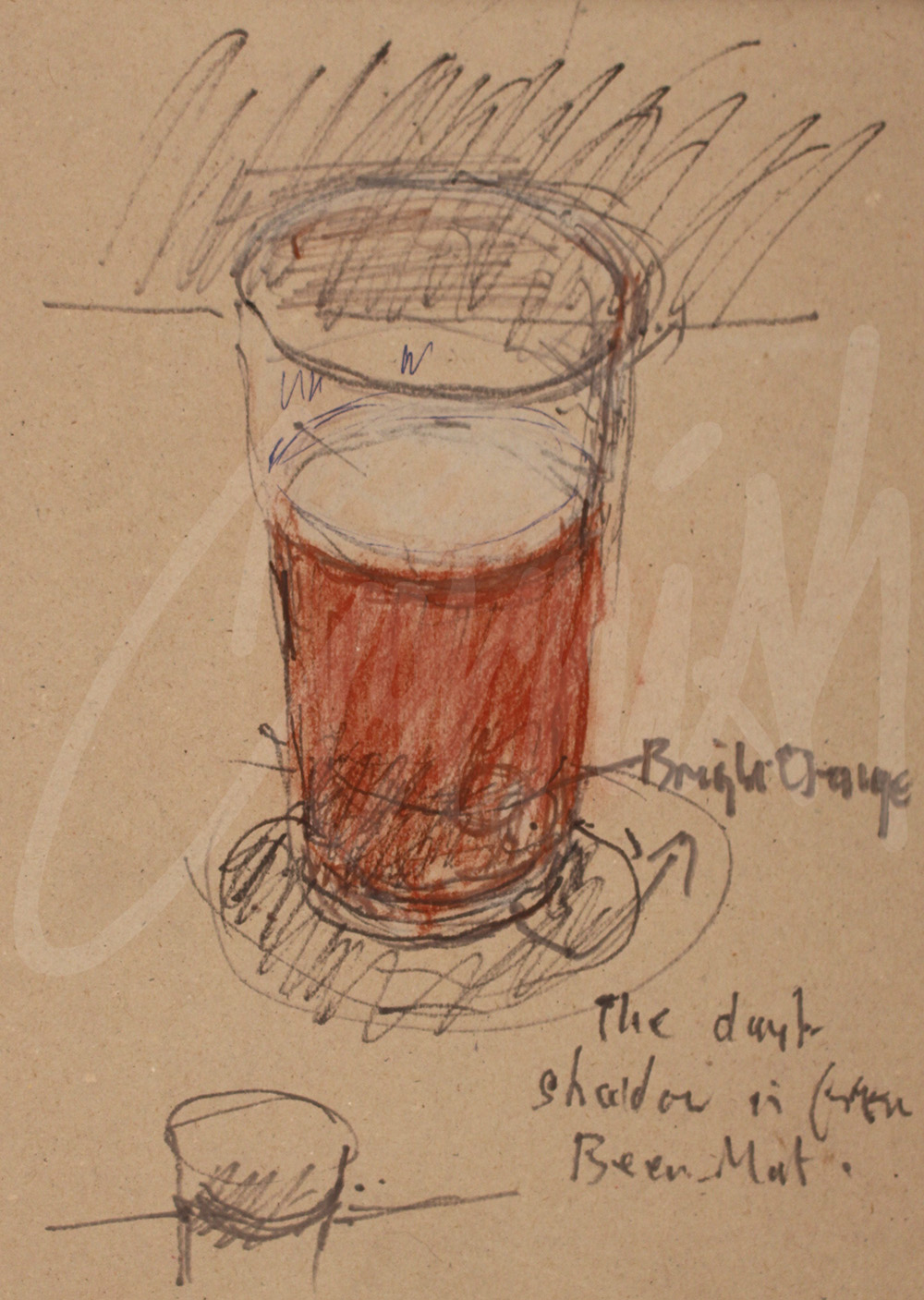

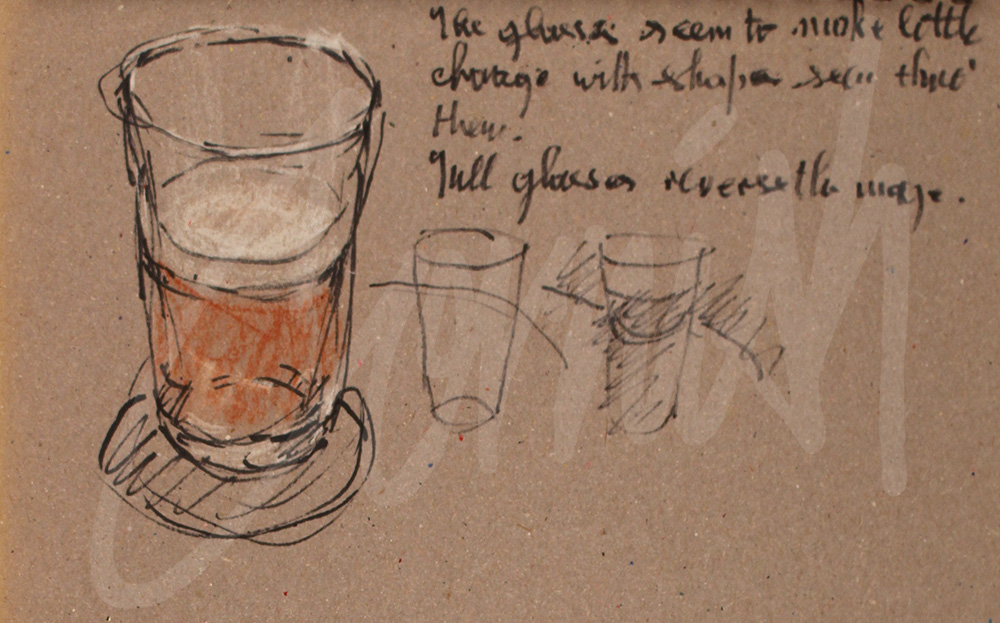

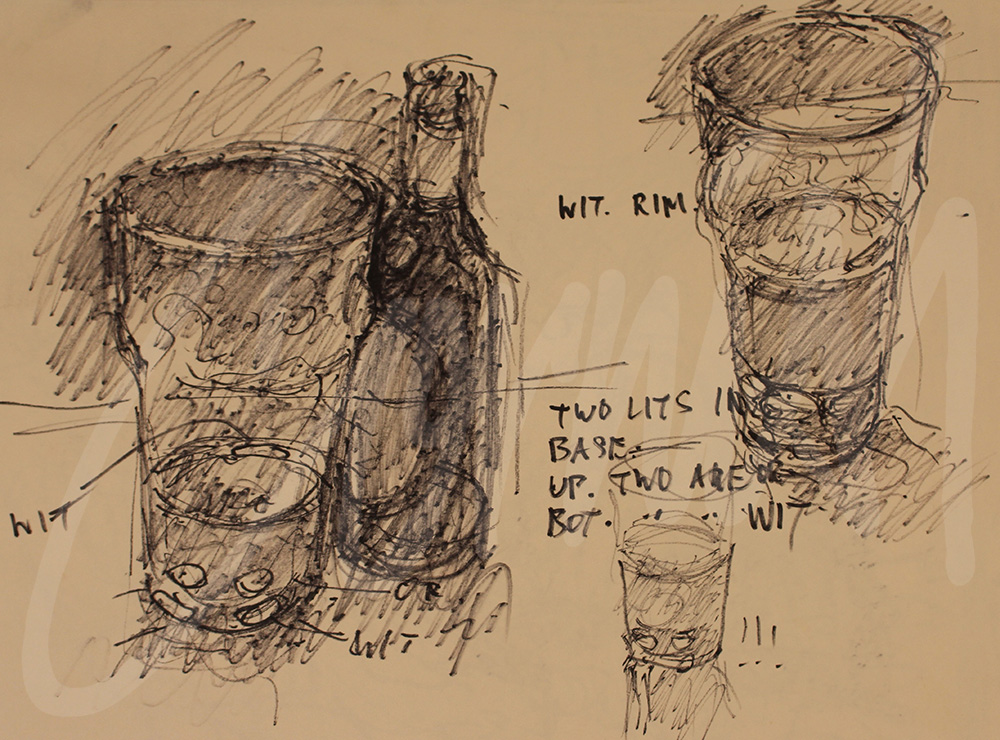

Cornish was advised at an early age to ‘draw and paint the things he knew around him.’ One of the surprising discoveries in Cornish’s 269 sketchbooks were his drawings of a ‘pint of beer.’

There are numerous examples in his sketchbooks and each includes references to colour notes, light, shade and other observational notes. The examples of beer glasses in bar scenes, with the contents at various stages of consumption or empty behind the bar are actually technical studies in their own right for a specific purpose.

Sometimes they appeared in the large bar scenes, but also with small groups of men or individuals, deep in thought with a pint.

Mining was physically hard work and the many pubs in towns and villages not only provided places to meet socially but also served a purpose to quench the thirst of the miners who had worked shifts of eight hours underground.

In his own words: “The accent is on atmosphere which contrasts the earthy humanism with the mysterious glitter of the beer and the glasses.”

No pitman’s home was far from a pub and there were 37 pubs in Spennymoor itself and a similar combined number in the surrounding villages.

Art critic Alistair Gilmour observed, “ Norman understands the pleasurable invitation that lies in a freshly pulled pint following a hard and dirty shift down the pit. You wipe away the first moustache of froth with the same hand gesture that wipes away the grime of the day.”

The bar scenes and character drawings in pubs, playing dominoes, darts, and enjoying ‘the craic’ feature as one of the chapters in Behind The Scenes; The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks, with many examples from this popular theme. Available at www.normancornish.com

For the record, Cornish’s favourite was a pint of Newcastle Brown Ale which he continued to enjoy with visitors in his final years.

Rosa Street School

The late 19th century was an interesting period in the emergence of Spennymoor as a town in SW Durham, midway between Durham and Bishop Auckland. In 1853 the Weardale Iron and Coal Company opened the Ironworks at Tudhoe and hundreds of immigrant workers arrived from the Midlands, Wales and Lancashire. As a town, Spennymoor came into existence in 1864 and the original Town Hall, situated on the High Street, opened in 1870. Spennymoor was ringed with collieries, blast furnaces and coke ovens. Very poor housing conditions prevailed and even by 1920 fewer than 10% of the town houses had water closets.

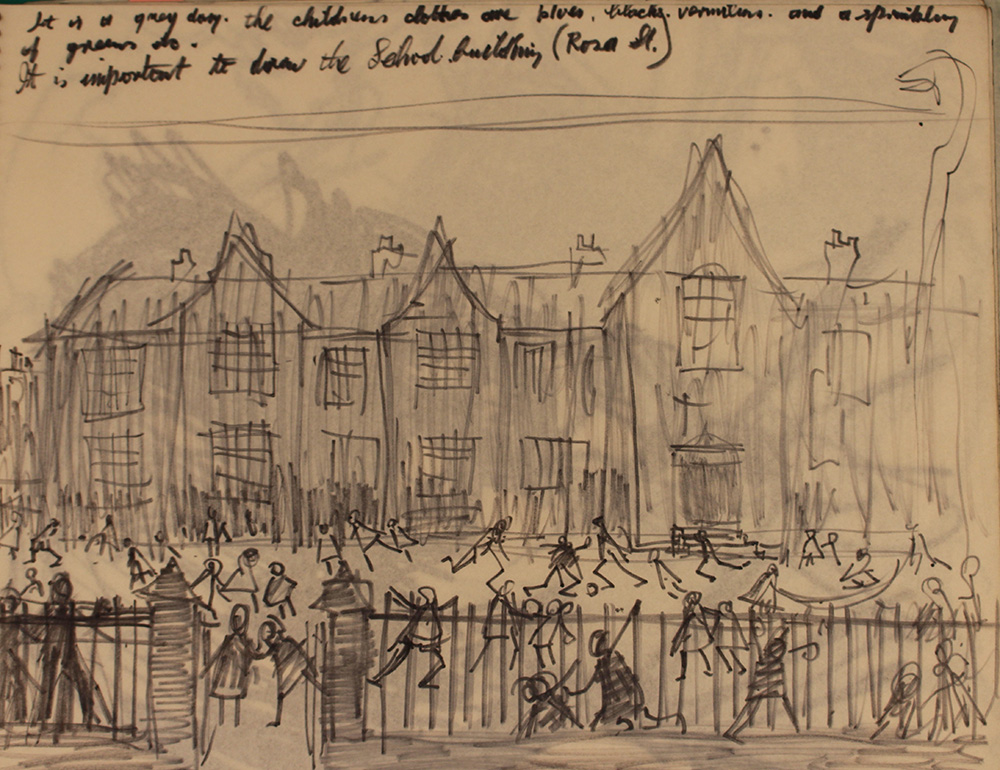

To meet the needs of an expanding population Rosa St School opened in 1870 and the external features of the school have remained unchanged. The school is situated near the lower end of Edward Street and viewing the ‘streetscape’ (previously unseen), Edward St can be seen with St Paul’s church ‘crowning the top of the street.’ To the left hand side, out of sight is the Zebra crossing providing safe passage for children, parents and grandparents taking children to and from school. Rosa St. School provides a focal point for children, parents with prams and all sorts of people going about their daily business. In his own words:

“Spennymoor has all that a painter needs in order to depict humanity.”

In May 2011 the Beamish Museum arranged a return to Spennymoor for the iconic Berriman’s Chip Van, following a period of restoration. The vehicle was parked at the side of the playground at Rosa St. School where staff from the museum were also in attendance. One afternoon Norman and Sarah Cornish also visited the chip van and after a short period of time a crowd gathered. A chair was quickly provided for Norman and he spoke at length about the chip van and Rosa St. School.

Rosa Street School is featured in ‘Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks’ along with St Paul’s Church, Edward Street and the Zebra Crossing, All are iconic locations featured on The Norman Cornish Trail. Details available at www.normancornish.com

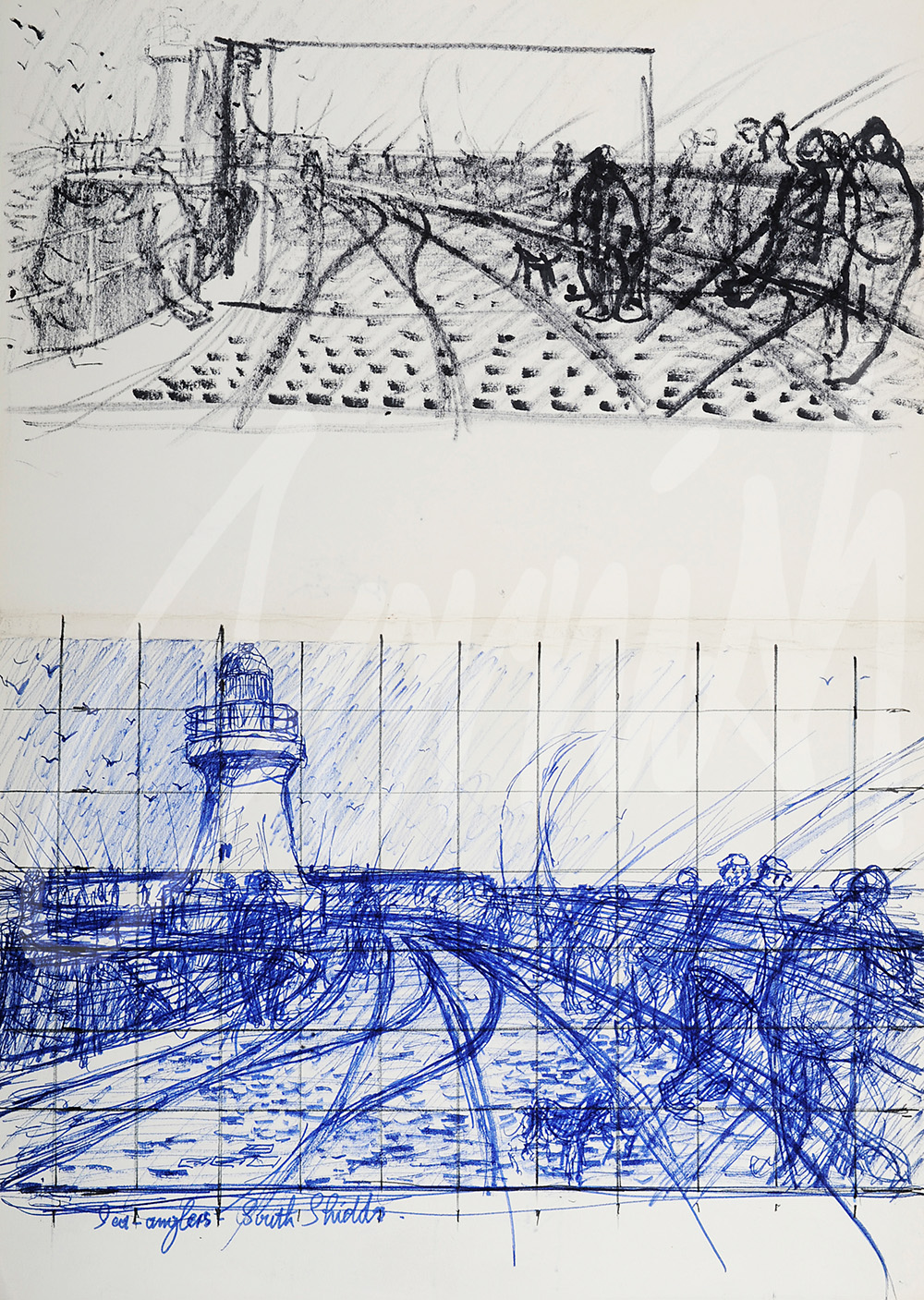

The Pier at South Shields

During the 50s and 60s the content of Cornish’s creative output was dominated by the subjects in his immediate surroundings; the industrial landscapes, the journeys to and from work, the pubs in Spennymoor, street scenes, observations of local characters and his wonderful record of the cultural landscape. He also exhibited alongside the work of other regional and national artists via the exhibitions at leading galleries in the north of England such as the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle, The Shipley Art Gallery in Gateshead, Tullie House in Carlisle and The Stone Gallery in Newcastle, which emerged as the leading commercial gallery in the region during this era.

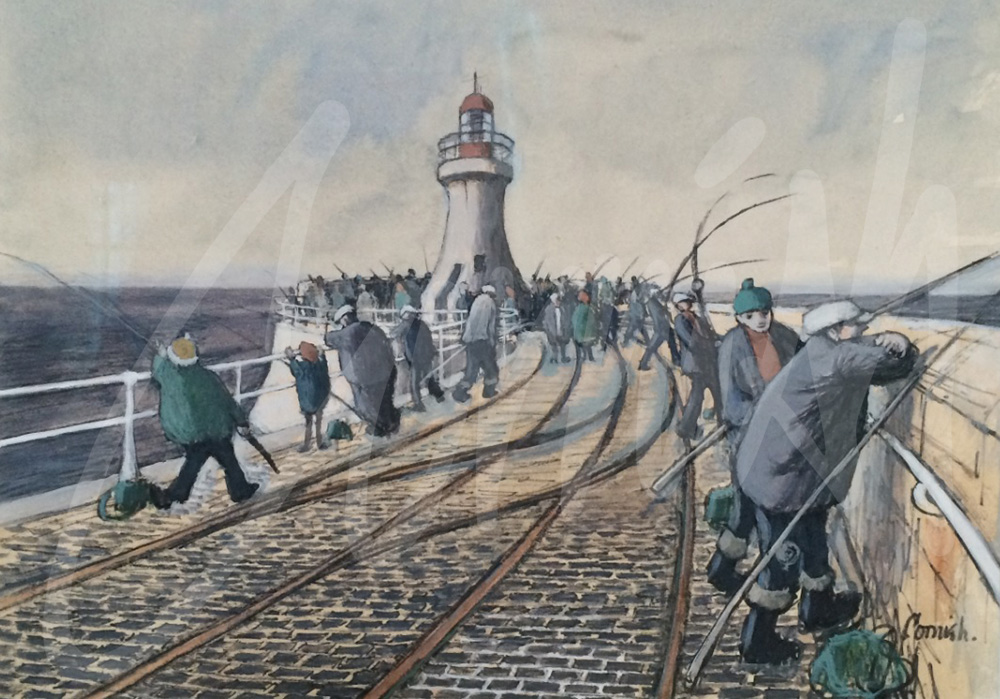

As a frequent visitor to Newcastle it was inevitable that the sights and sounds of Tyneside would begin to exert some influence on his choice of subject material. His first painting of people fishing at South Shields appeared in the Stone Gallery exhibition of 1967 which was shortly after his step towards becoming a professional artist.

The pier at South Shields was an obvious attraction for an artist interested in people and places. In his own words:

“ the people make the shapes, I am just the medium.”

The south pier at South Shields is 1,570metres long and combines the interesting curvature of the feature, along with the rail lines used in the construction of the pier in 1854. The anglers watching and waiting after casting their lines, were irresistible to Cornish, and the subject became a favourite that also offered what he considered as “a different theatre of operations.”

9 preparatory sketches of the pier and anglers in action, along with 3 completed paintings and a photograph including his wife Sarah, appear in Behind the Scenes: The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks. The preliminary work clearly illustrates the detailed research which he undertook to ensure technical accuracy as well as capturing moments in time.