Latest News

Norman Cornish, Spike Milligan and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Located in the Norman Cornish archive at Northumbria University there lies a significant letter from Spike Milligan, comedian, writer, poet, playwright and actor, who became an admirer of Norman’s work.

In November 1961, a programme by Tyne Tees Television featured The Northern Sinfonia Orchestra, the Consett Citizens Choir and guests John Gilpin, Joan Hammond and Doreen Wells. The programme was compered by Spike Milligan. One of the features was the presentation of original paintings and drawings by Norman Cornish, along with prints by Toulouse-Lautrec.

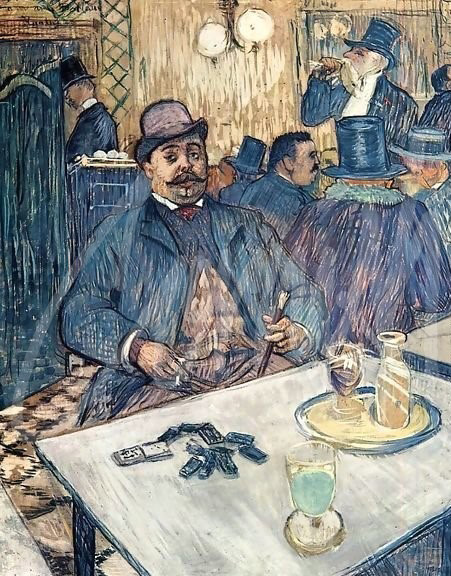

The producer of the programme, Peter Glover, commented: “The paintings of pit village life by Spennymoor artist Norman Cornish, and those of Toulouse-Lautrec, have an affinity. Each portrays faithfully the environment in which he finds himself.”

Toulouse – Lautrec is amongst the best-known artists of the Post-Impressionist period, along with Cezanne and Vincent van Gogh. Toulouse-Lautrec captured the culture and atmosphere of the French cafes and he became a master of painting crowd scenes where each figure was individualised. Spike Milligan wrote to Norman after the programme was broadcast, asking if he could buy an example of his work, ‘Not because it may be valuable, but because you’re a bloody good draughtsman’

In Cornish’s own words: “I believe that in some way I have been influenced by almost every picture that I have ever looked at. I have been much influenced by the work of the important masters: Rembrandt’s drawings, early Van Gogh, Breugel, Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec, Cezanne, and maybe Lowry, to name but a few. However I have resisted being swamped by their influences, utilising their influence instead as an education in mental and visual awareness.”

Image: Monsieur Boleau-In-A-Cafe Toulouse Lautrec

The Durham Book Festival

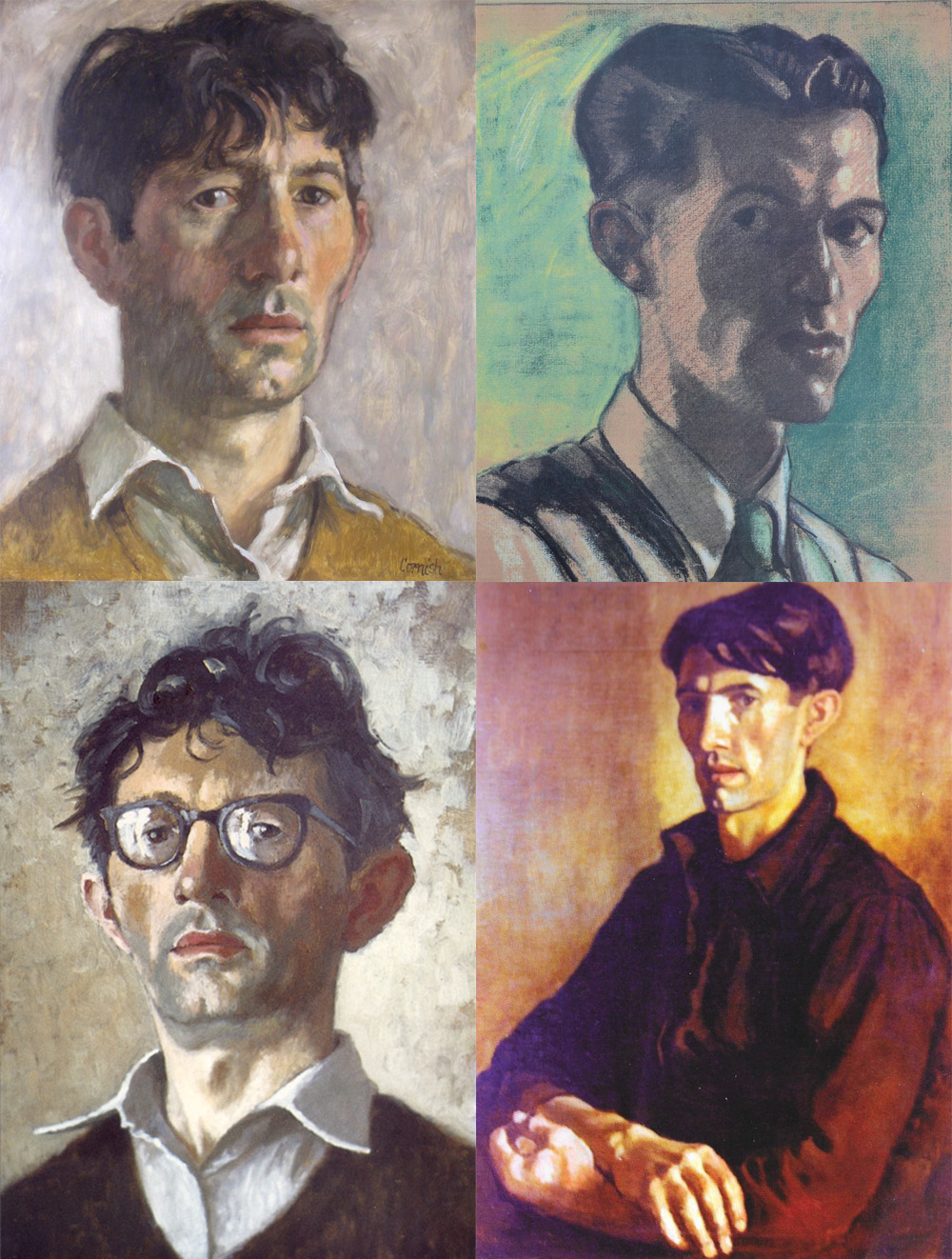

The Test of Time is a new book celebrating the life and work of the late Spennymoor artist Norman Cornish, which reveals some of the fascinating stories behind his pictures.

In two special events to mark the publication of the book, Norman’s son-in-law Mike Thornton will talk to writer Michael Chaplin exploring the stories, history and anecdotes behind the moments of County Durham life captured in Cornish’s acclaimed paintings. Drawing on the 50 years Mike spent in conversation with Norman, these events will celebrate the legacy of a great artist and provide insight and access to a slice of art history. The discussions will be supported by examples of paintings and drawings representing the full canon of Norman’s work.

Michael Chaplin’s father Sid, was a contemporary of Norman Cornish at The Spennymoor Settlement and also a ‘marra’ at Dean and Chapter Colliery. Michael Chaplin has written the Foreword to ‘The Test of Time’ and he has known Norman throughout his own lifetime.

Michael Chaplin is a former journalist, television producer and executive. He is a writer with many credits in drama for radio, television and the theatre, and author of various books of non-fiction about the North- East.

Details about The Durham Book Festival and ticket access to both events will be published at www.normancornish.com and newwritingnorth.com on Thursday August 17th at 8am.

‘The Test of Time:’ A new book about the life and work of Norman Cornish

We are delighted to be part of The Durham Book Festival 2023 and specific details of the launch in October will be published fairly soon.

The Test of Time’ includes over 400 images spanning the depth and breadth of his career. Many are previously unseen and will be published for the first time, evoking memories and nostalgia from a bygone era.

‘The Test of Time’ collates the stories behind the pictures, the legacy projects, and a collection of informed essays from nationally respected arts and cultural specialists who have known and enjoyed Cornish’s work throughout their own lifetimes including:

Michael Chaplin, Melvyn Bragg, Andrew Festing MBE, Dr Robert McManners MBE, Gillian Wales, Steve Swallow, Chris Lloyd, Dr Steve Howell, Dr Keith Wilson, Pam Royle & Dr Cesar Lengua.

To be continued ……

The Test of Time

The daily news can be both depressing and up-lifting and not always in equal measures. Many of our readers most likely enjoyed the exhibitions during the centenary year and one of the highlights of course was the retrospective exhibition at The Bowes Museum where over 53,000 people travelled from all parts of the UK to enjoy the works on show. There should be some announcements in the coming months to share plans about a new exhibition in 2024.

One of the more unusual highlights at The Bowes Museum in 2020 during ‘the hanging’ (pictures not staff) was an interview by BBC Radio 4 Today (listening figures 6 million+) when the interviewer asked Associate Professor Jean Brown of Northumbria University, the question, “Will his work stand the test of time?” to which she replied: “Absolutely – because he is up there with Rembrandt, Degas and Lautrec.”

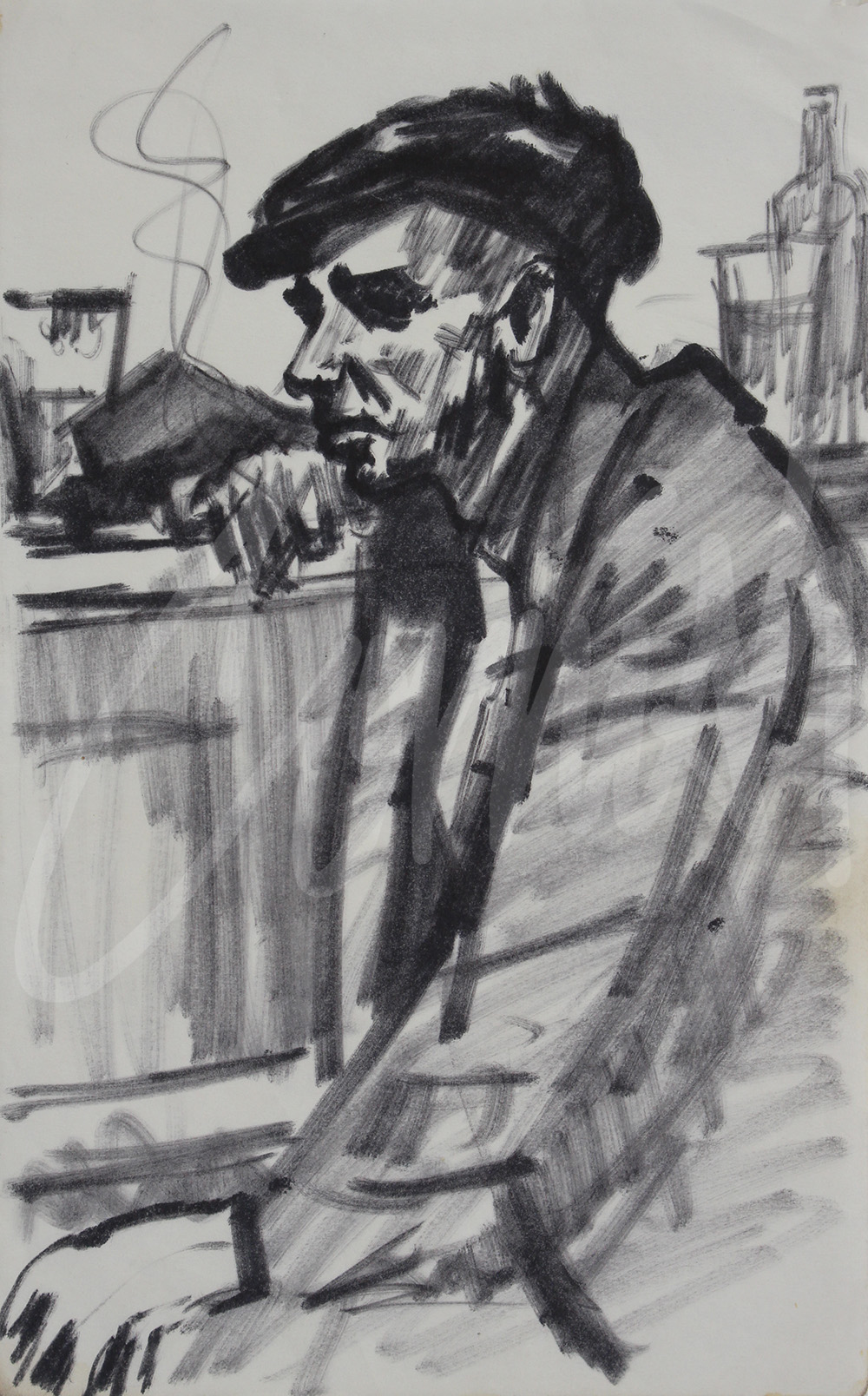

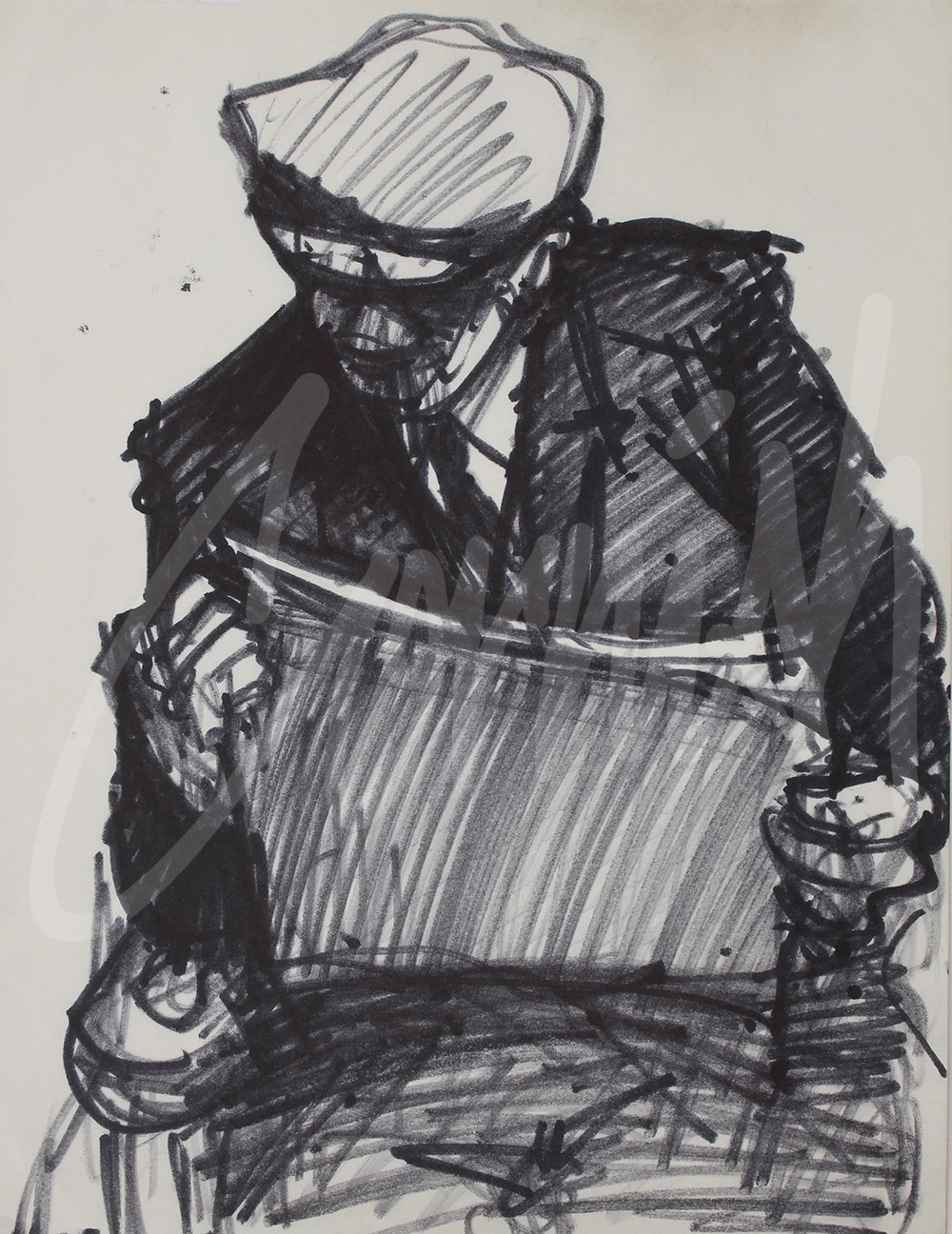

Great works of art inevitably stand the test of time and there is an authenticity in Cornish’s work which spans his era and, in the ‘wheel of art’, often generating new ‘isms’, Cornish remains at the hub. He has become an anchor point in the wider arts community, building on social realism without shifting towards abstraction and decoration.

‘Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks’ published in 2017 revealed the detailed creative process in Cornish’s sketchbooks. The test of time concept has provided the inspiration for a new book to collate the stories behind the pictures and the legacy projects. It is accompanied by a collection of informed comments from nationally respected arts and cultural specialists who have enjoyed Cornish’s work throughout their own lifetimes.

For over 50 years we spent many hours in conversation with Norman, listening as he shared highlights of his life and work. This experience enabled a special insight to a treasure trove of historical moments and anecdotes. The stories behind much of his work were revealed to provide unrivalled access to a slice of art history.

Some good news…… We have been working for the past 18 months on this new book, ‘The Test of Time’ which will be launched in October. The front cover is featured today. Details about the book and arrangements for the launch will be published during the coming weeks. To be continued…….

Hanging on the Walls

Following a sustained period of working in his studio, without a gallery to promote his work via exhibitions, the opportunity to develop a relationship with the University of Northumbria Gallery from 1989 proved to be mutually beneficial at a crucial stage in Cornish’s career. The gallery became a point of contact for the media and collectors of his work, and also a venue for numerous exhibitions which followed. The gallery was also able to relieve Cornish of the task of framing his own work which he had undertaken for many years.

Eight exhibitions were staged at the University Gallery between 1989 and 2013. Cornish always attended the preview and made himself available to meet and talk to those who were interested in his work. This became a challenging task as he was in the twilight of his career, but he was always willing to meet and talk to people. On one occasion there was a ‘live broadcast’ directly from the gallery by Tyne Tees Television, such was the interest in his work and the opportunity to hear Cornish speak.

Exhibitions often toured to other galleries in the region such as: Hartlepool Art Gallery, Woodhorn Museum Ashington, Bailiffgate Museum Alnwick, Customs House Gallery South Shields and The Queens Hall, Hexham. One man exhibitions were also staged at Sunderland Museum and Art Gallery as well as The Greenfield Gallery in Newton Aycliffe.

Cornish first exhibited in London on several occasions during the 50s, and he was delighted that his work was returning to the capital at this point in his career via exhibitions at Piano Nobile, Barings Bank and two exhibitions at Kings Place Gallery.

At one of the private views, the Vice Chancellor of the university spoke at length about Cornish and his work to the assembled audience. He finished his speech by inviting Cornish to comment, which he did, with some well-chosen words: ‘Everything I have to say is hanging on the walls.’ A powerful statement from an artist who had captured significant change in communities across the region during his slice of life.

Further details may be obtained by visiting www.normancornish.com

More Articles...

- Community Arts: Inspired by Norman Cornish

- Vincent van Gogh

- Norman Cornish 1973-2013 Academic success and national acclaim

- Parents: Jack and Florence

- The Port of Tyne Commission Part 1: Roll-On Roll-Off

- Norman Cornish in the 80s

- Man at Bar with Dog: A Masterclass in Art Appreciation

- Edgar Degas

- Edward Street

- A Missing Link