Latest News

Ted Harrison

In 1947 Cornish was invited to exhibit in the ‘Art by The Miner’ exhibition at the Academy Cinema in Oxford Street, London, to be opened by Prime Minister Clement Attlee. Norman actually hung the exhibition and in some spare time he visited the Reeves shop in Camden Town. It was during this visit that he first encountered the Flo-master Pen, nibs and ink; but sadly, he was unable to afford the cost of buying the pen.

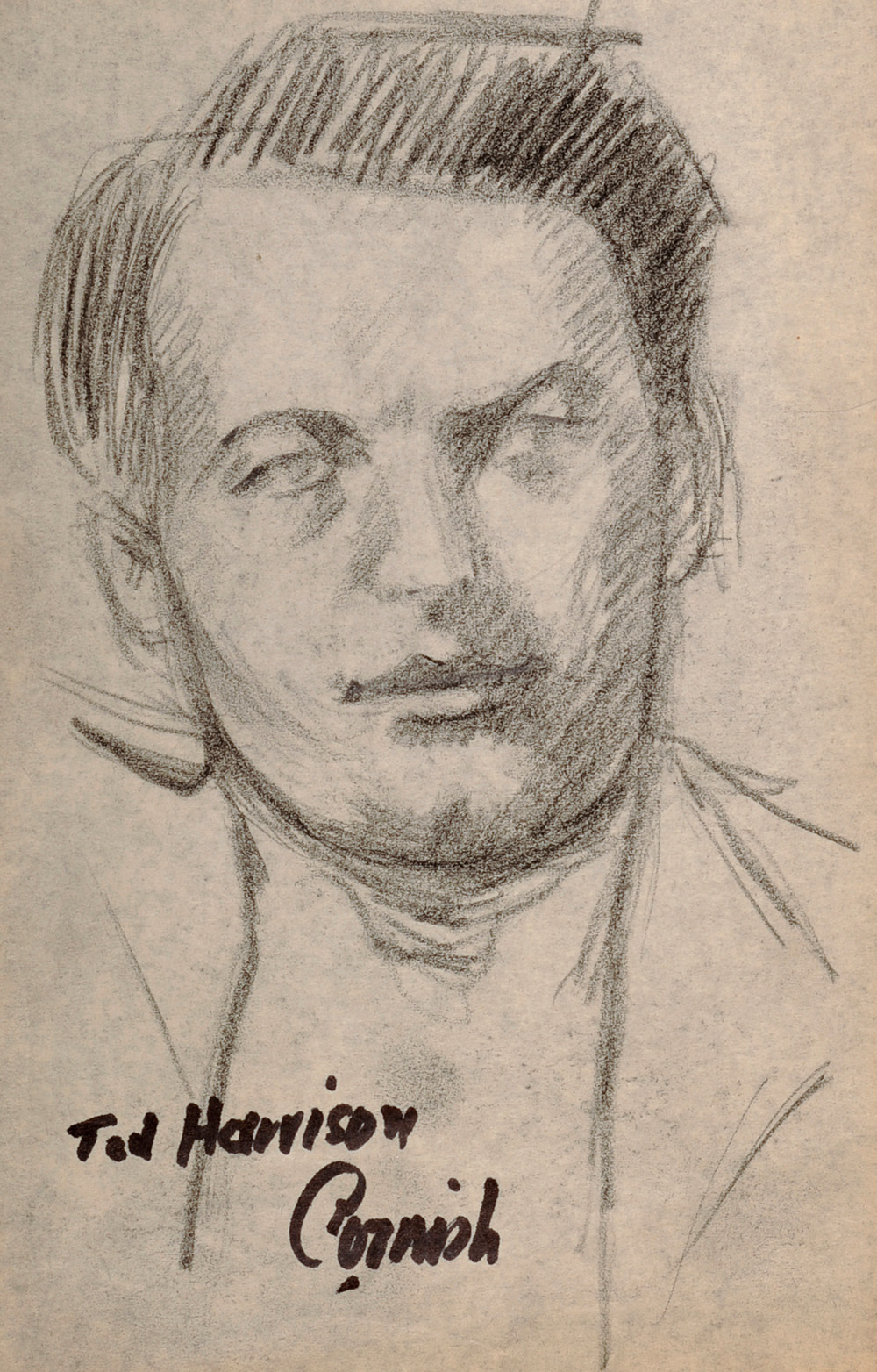

Such was Cornish’s growing reputation that in 1951 he was invited to a weekend course at Wallington Hall, Northumberland, as a guest tutor along with John Minton and Harry Thubron, two very experienced artists and tutors with national reputations. One of the participants at Wallington Hall was the slightly younger Ted Harrison who was born in 1926 in Wingate, County Durham. Ted started to paint at West Hartlepool School of Art and after the war he qualified as a teacher from the University of Durham. Ted found his formal training uninspiring and rather disappointing. Undeterred, he and Cornish, whom he referred to as ‘Cornbags’ became both contemporaries and personal friends often visiting each other at their respective homes. Ann and John Cornish have many happy memories of meeting and enjoying the company of ‘Uncle Eddy’ and his flamboyance, as well as his interesting art in unusual locations around his family home in Wingate.

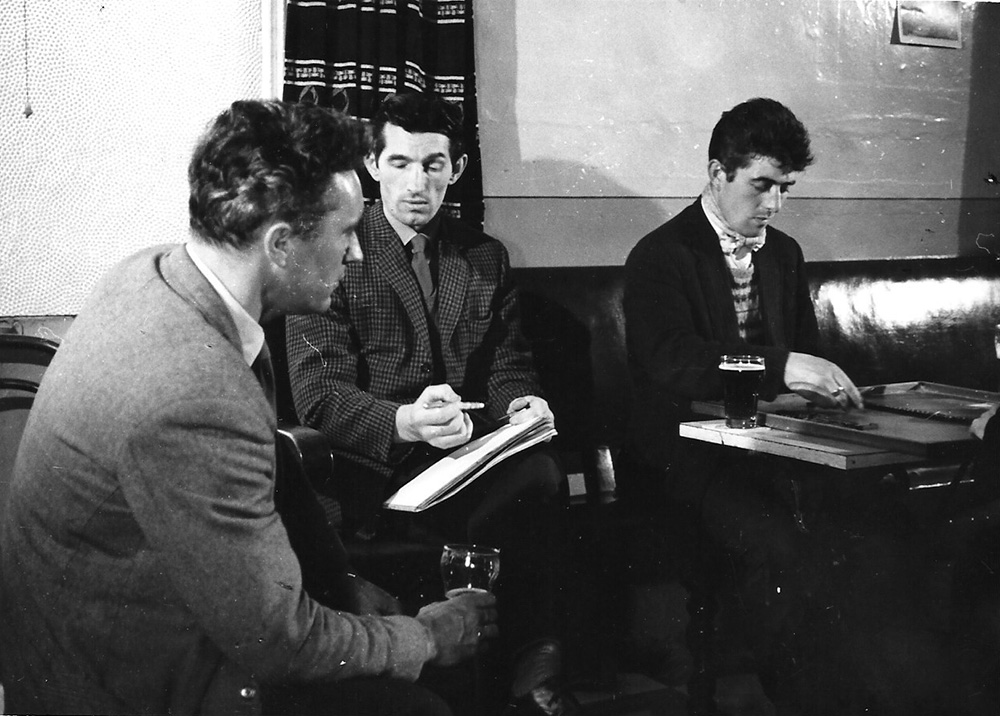

Ted would also visit Norman and Sarah Cornish at Bishops Close Street where Norman and Ted would nip along the road to The Bridge Inn at the end of the street and enjoy a pint, drawing characters in the pub, and discussing art, literature and philosophy.

Ted emigrated to the Yukon in Canada in1967 and thereafter became one of Canada’s most famous artists and the recipient of three Honorary Doctorates as well as a member of the Order of Canada for his contribution to Canadian culture. Both artists maintained their contact via regular correspondence which is now located in the Northumbria University archive.

Ted Harrison was very grateful to Norman Cornish for inspiring his life long quest to paint people and places. Norman Cornish was eternally grateful to Ted Harrison at that first meeting at Wallington Hall, when Ted purchased something for Cornish which enabled him to take his drawings to a new and exciting level – a Flo-master Pen. The rest is history, and the quality of Cornish’s drawings has been compared, ‘as good as any other artists in history’ - Andrew Festing, former President Royal Society of Portrait Painters.

Allotments and Pigeon Cree

Today in County Durham there are 159 allotment sites thriving in towns and villages continuing a tradition which began in the 19th century and originally created for the working man to provide additional food throughout different seasons. Looking after an allotment became a worthwhile activity, which was very much part of the cultural landscape of mining communities.

Growing vegetables also became competitive in the Autumn during the annual ‘Leek Shows’ where prizes were awarded for the biggest and best specimens in each category. This annual tradition remains at the heart of many communities today and the seeds obtained from prize-winning vegetables are highly valued. Sabotage sometimes occurred between rival growers and examples of ‘Leek slashing’ are legendary.

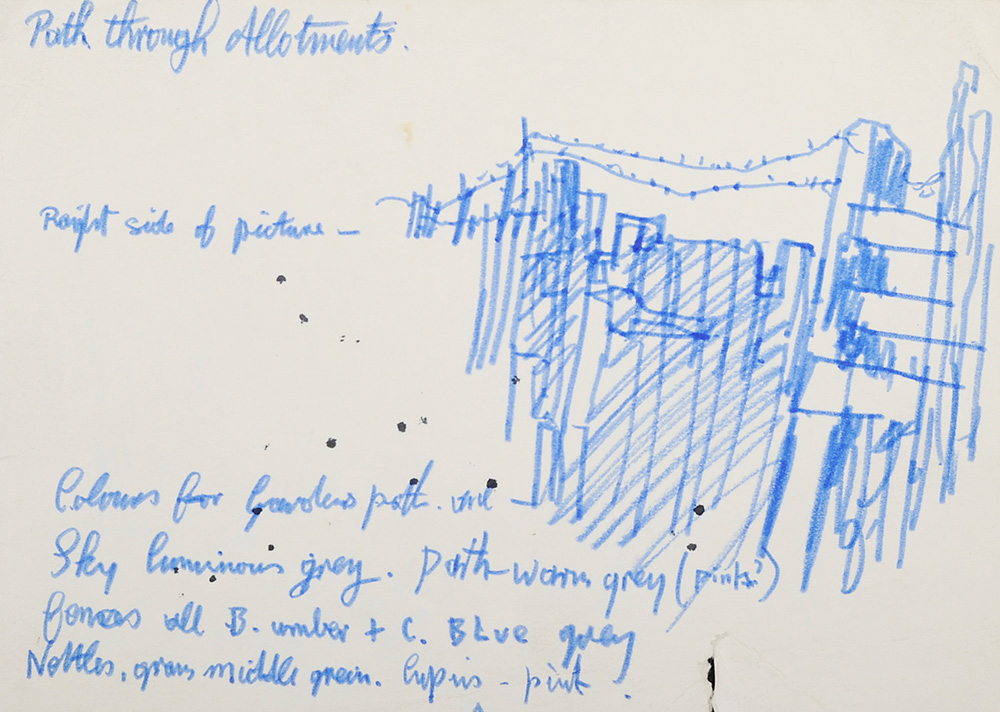

Cornish was advised at an early age to paint ‘the things around him’ and it was inevitable that with so many allotments and pigeon crees in the Spennymoor area they could hardly fail to become a subject of interest. The daily walk to and from Dean and Chapter Colliery passed by the allotments in Low Spennymoor, and conversations with his ‘marras’ would reinforce the interest. The local ‘Leek Shows’ never appeared as a subject in his work but posters advertising ‘Leek Shows’ sometimes appeared in his bar scenes.

During the research phase for the 1950s town by staff at Beamish Museum Sarah Cornish recalled the annual occasions in Bishops Close Street when a pig was slaughtered at one of the local allotments and the carcase shared amongst families in the street, such was the value of sharing in the community. Other livestock were also kept in some allotments including poultry and of course, pigeons. Back yards were also utilised and Cornish’s father kept Zebra Finches, Budgerigars and Canaries in a special cree in the backyard of his house a few doors away from Cornish’s home in number 38 Bishops Close Street.

Pigeon crees were also very much part of the allotments as an additional past-time and two of the images record that moment in time when pigeons ‘homed in’ on the cree! One of the images, included is The Holy Innocence Church in Low Sennymoor which features in all of the pictures of Salvin Street, with allotments at the bottom in front of the church. Basically it is a detailed study usually incorporated into the larger street scenes of Salvin Street.

Keeping allotments remains embedded in the cultural landscape, not only in County Durham but also further afield as part of our national heritage. In England there are over 7,000 sites with 245,000 plots, and in Spennymoor the tradition continues to flourish on 16 sites with 655 allotment holders.

Cornish often referred to his ‘disappearing world’ but he would have been delighted that the interest in allotments has been sustained during a period of significant social upheaval. The images featured can be enjoyed in Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks, available via the website www.normancornish.com

The Gantry: Part 2

Cornish vividly recalls the first time he entered the cage on his first day at work.

In his own words:

As we stooped to enter the cage, which held 20 men at a time I was comforted by the fact that I was amidst experienced men quite used to the descent into the pit. The cage dropped very rapidly. About halfway down I felt that I was coming up-over. We finally landed at the shaft- bottom and I was relieved to find that it was well lit by electric lights. A tunnel curved away in the distance. My mining career had begun.

At the Stone Gallery exhibition in 1960, Cornish was introduced to Lord Lawson of Beamish, who was born in Whitehaven in 1881, moved to Boldon Colliery aged 9 and worked underground as a ‘trapper’ from the age of 12. Jack Lawson, a former miners’ leader, was elected to Parliament in 1919 as MP for Chester-le-Street and became Secretary of State for War 1945-46. He was also Lord Lieutenant of County Durham 1949-58. Jack Lawson and his wife invited Norman and Sarah to tea at his home one afternoon and a car was sent to collect them. After tea he suggested that he and Cornish have a chat in their front room and Jack Lawson produced a copy of his autobiography, ‘A Man’s Life’, which was a favourite of Cornish.

Lawson opened the book and read aloud the chapter describing the pit cage descending from the gantry, leaving Cornish with a much treasured memory. ‘A Man’s Life’ was a firm favourite on the bookshelves at Whitworth Terrace and it was humbly inscribed to Norman Cornish, miner artist, from the author Jack Lawson.

The book also delves into the challenges faced by miners: to overcome prejudice, the disrespectful treatment by officials and lost opportunities to continue their education. In one of the chapters, there is a reference to a poignant moment under-ground, and in total darkness, when pausing between strenuous activity, two of Lawson’s colleagues continue a conversation about the salient points in a specific Greek play.

Cornish worked hard as a miner but frustration crept in as he wrestled in his mind with the fact that a colliery was geared to coal production and not art appreciation.

The Gantry: Part 1

Cornish arrived cold and damp from walking over two miles in heavy snow to start work aged 14, at 2am, on Boxing Day 1933. He had no choice, and was denied the opportunity of continuing his education because he was the oldest in his family of five brothers and one sister.

There were over a hundred collieries and pits including quarries, brickworks and coking plants within a five miles radius of Dean & Chapter Colliery, at various stages or working, closing or dormant. The smoke and sounds of the railway engines hissing, coal trucks, colliery buzzers, and miners’ boots on the steps combined to create an industrial cacophony. The impact upon the environment and the men was pervasive.

He was offered a job as an underground datal ( paid by the day) lad and when he signed on the dotted line the official said in his deep voice: “You’ve just signed your death warrant son.” The pit was nicknamed locally ‘The Butchers Shop,’ owing to the number of accidents there. The records of 177 fatalities make for sober reading although there were no ‘disasters’ (officially five or more killed together, by gas explosion for example).In 1935 there were 2,135 men and boys working underground and 538 above ground. By 1937 the workforce was producing 3,000 tons of coal a day – a third of it machine - mined and the rest hand hewn.

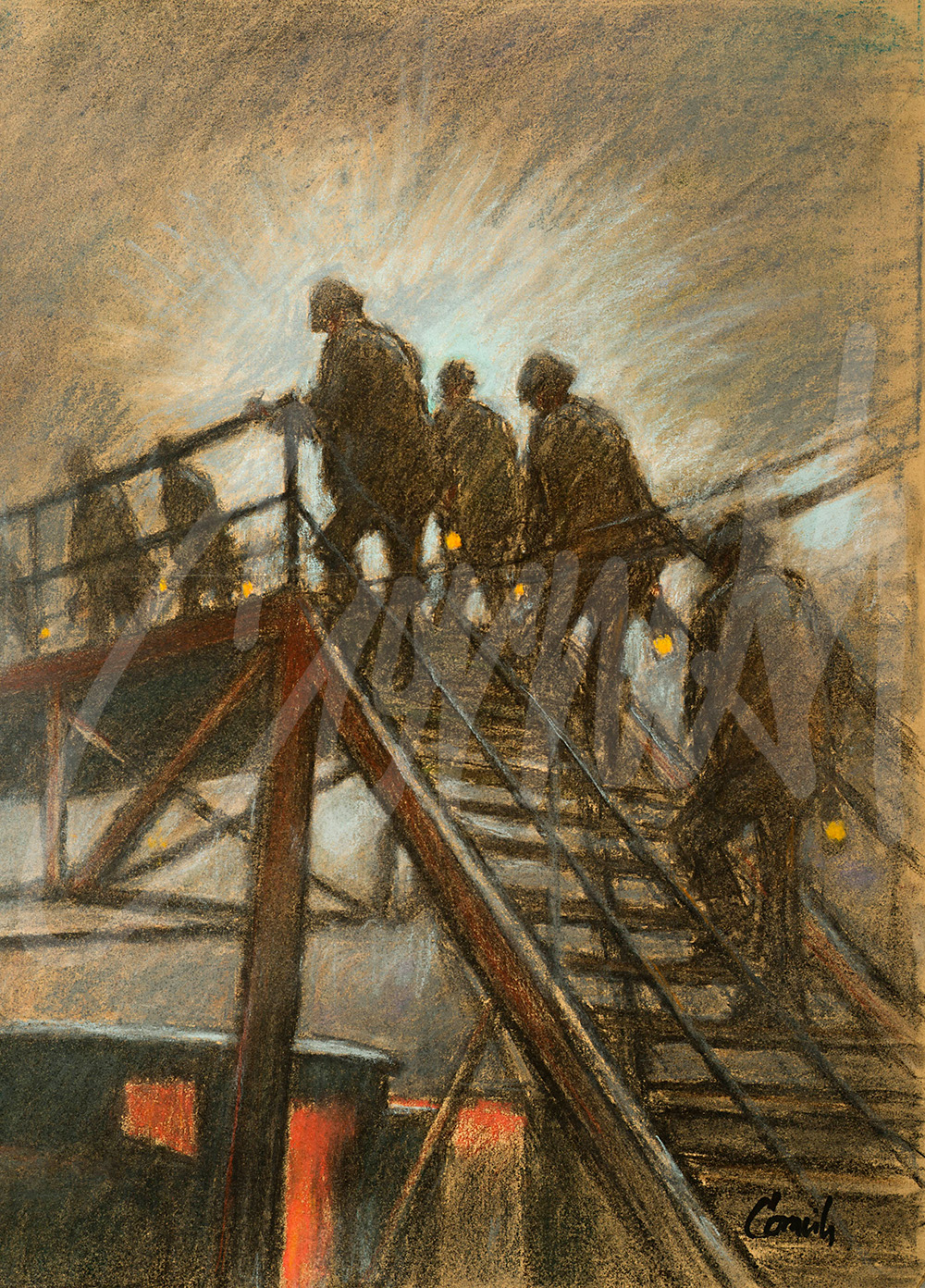

On his first day he was given a lamp and a disc and moved out of the lamp cabin to be confronted by a flight of steel steps leading on to a gantry which crossed the mineral line. The gantry led onto the cage bank level which was at the opposite end of the gantry wheels and ropes. As the shunting engine passed below them, they became lost in a cloud of steam which reflected the arched window lights of the colliery like a cinema screen.

In his own words:

I went through the door and the first thing I saw was the gantry scene. The men were there with their orange oil lamps and they looked like fireflies. Then I saw a mass of steel railings, steps, girders and steel wires. I thought it looked like a great steel spider’s web and when I saw the colliery behind, I thought it was like a giant big spider – moving towards us and then going to drop us down a great hole.

The picture is about feeling – what I felt and saw as a boy.

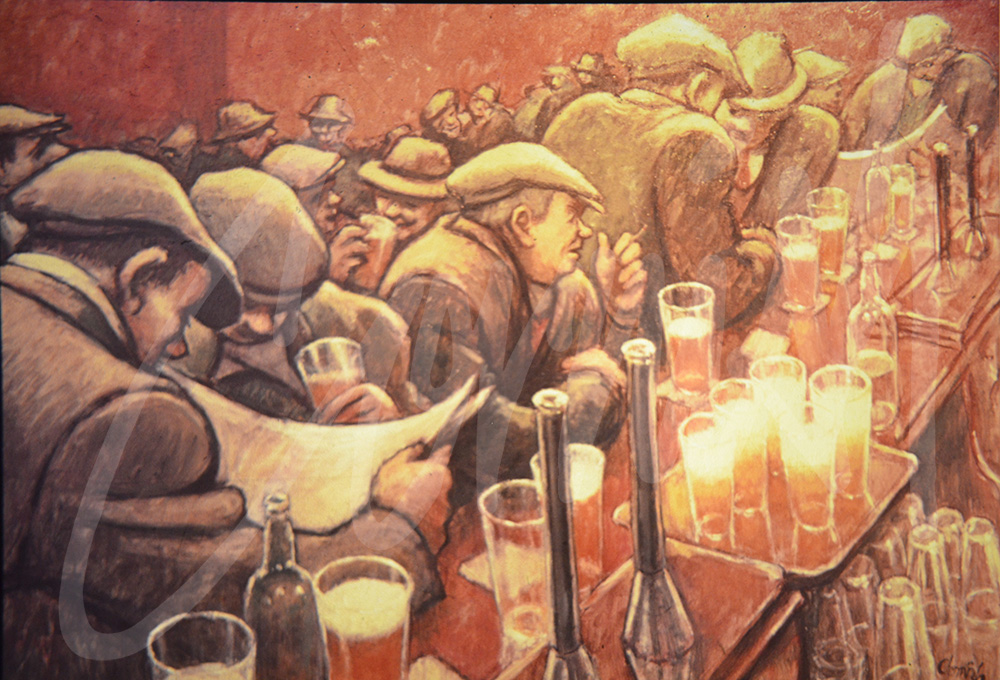

The Busy Bar: Human Drama

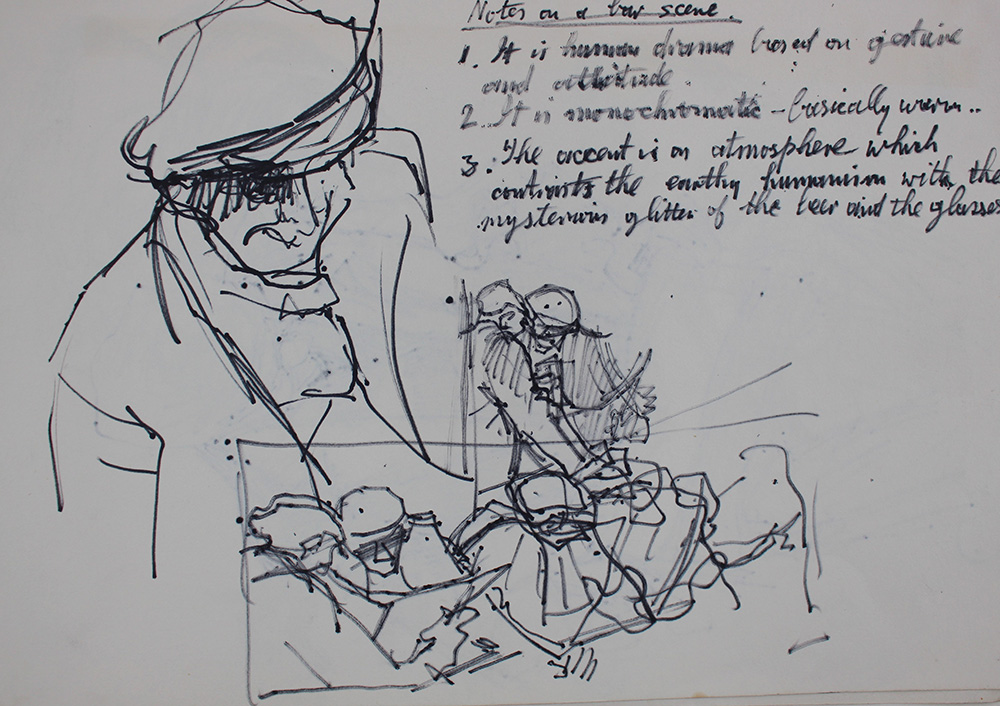

Norman Cornish’s studio is currently on long-term loan from Beamish Museum to Spennymoor Town Council, and is the centre-piece of the Coming Home exhibition at the Bob Abley Gallery. In 2014, a scrap of paper was discovered in the back of a drawer in the studio table.

The scrap of paper revealed for the first time a preliminary rough sketch of a bar scene. More significantly, there were three statements setting out the underlying principles which Cornish employed to develop the composition of The Busy Bar, which became one of his most admired and appreciated paintings.

- It is human drama based on gesture and attitudes.

- It is monochromatic

- The accent is on atmosphere which contrasts the earthy humanism with the mysterious glitter of the beer and the glasses.

A fascinating insight, which discloses his deep thoughts about the underlying geometry of the picture. A clear and carefully considered structure, with a highly complicated design and unusual perspective from the barmaid’s view helps to invite us into this busy bar full of activity and animated conversation.

In his own words:

Again, the bar is a big diagonal shape – wide bar coming along half way up the right-hand side down to the section area of the base. Then, of course, there are other shapes teetering away from his hand, down to under the bar. It’s not too obvious, but it is two diagonals, one against the other - rather like when you see someone playing a violin. You need a violin and you need a bow to cross in order to get music. If you don’t do that, you don’t get a lot of music – it helps to create feeling. Of course, the actual men themselves created circular rhythms within the group. The circular rhythms knit together like a jersey.

As an underground miner, Cornish was fully immersed in his community. The beer in Cornish’s glasses gave him the passport to be able to share, observe and record the communal life in pubs because he was easily able to blend in and this gave him the opportunity to produce so many character drawings of his subjects.

In 1989 The Busy Bar was purchased by Scottish & Newcastle Breweries to be hung in their boardroom. In 2007, the painting was donated to The Permanent Collection at Northumbria University.