Latest News

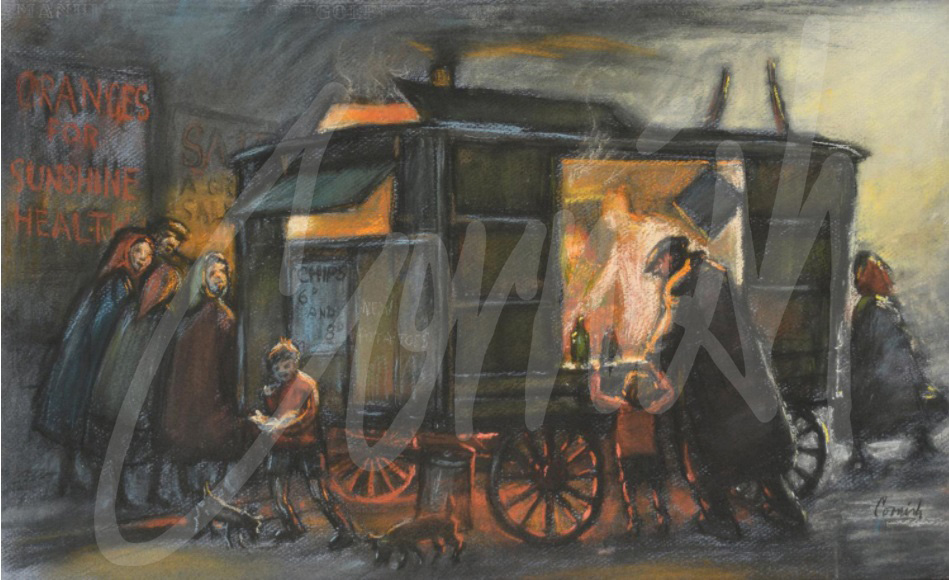

Behind The Scenes: Berriman’s Chip Van

Cornish’s work provides an important social record of the cultural landscape of his era and there is no finer example than Berriman’s chip van. An early version of the modern ‘takeaway’ but forever immortalised as an icon of a period of time in Spennymoor. The chip van had several locations during its life-time but eventually located near Thomas Street, a short distance from Bishop’s Close Street and remembered as one of the locations on the Norman Cornish Trail.

Not only did the three Berriman brothers grow their own potatoes, they brought them to the chip van ready peeled and the fishcakes were later supplied from Hanselman’s fish shop, across the road on the High Street. Sue Snowden (nee Hanselman) Lord Lieutenant of County Durham, remembers with pride and affection how her father supplied fishcakes of the finest quality to the Berriman brothers.

The chip van was acquired by Beamish Museum in 1972 when the brothers retired. After a number of years the restoration was undertaken by Staingate Restorations so that it would become available in the museum as part of the collection. The chip van made a nostalgic return to Spennymoor in 2011 for three days at Rosa Street School and Cornish was able to spend some time talking to visitors and staff from Beamish, sharing his memories. Cornish and the famous chip van later appeared in a BBC documentary with Dan Cruickshank who discussed this piece of local history in the artist’s studio. Berriman’s Chip Van is now parked near the High Street in the 1950s Town at Beamish Museum where you can also visit 33 Bishops Close Street, the Cornish family home from 1953 until 1967.

In his own words:

The chip van used to belong to George Kirtley but was taken over by the Berriman family and changed appearance. They kept all of the cooking pots, the pans, the chip maker and the little cupboards where the potatoes were kept. I knew the family. They used to live in Duncombe Street, opposite the Town Hall, and had a yard where the horses were kept. They also used to deliver coal and had a funeral business with black horses and black hearses. On a Saturday night when everything was closed, they would use a horse to bring the chip van back to their yard for safe keeping and bring it out next morning. The three brothers grew their own potatoes and when they were working, one was slicing the potatoes, one serving and the other in the pub!

I knew all three lads, Dougy the oldest, Billy and Dickie. They had another older brother I never actually knew until I met him down the pit as we were coming out.

Because I am an artist who paints people, this chip van is a must, an obvious good subject for a painting.

Berriman’s Chip Van is one of the subjects featured with additional drawings and images in Behind the Scenes: The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks available on line at www.normancornish.com

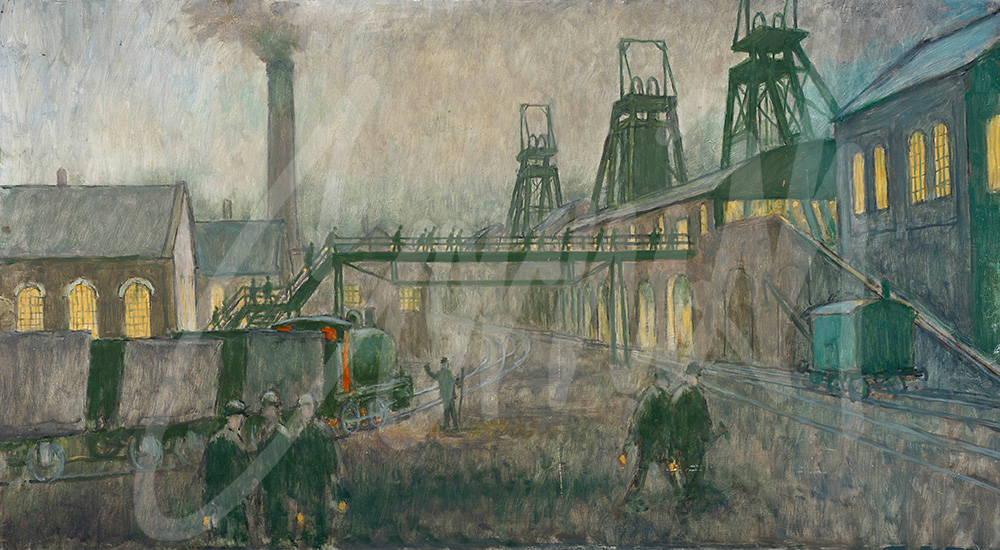

The Gantry: Part 2

Cornish vividly recalls the first time he entered the cage on his first day at work.

In his own words:

As we stooped to enter the cage, which held 20 men at a time I was comforted by the fact that I was amidst experienced men quite used to the descent into the pit. The cage dropped very rapidly. About halfway down I felt that I was coming up-over. We finally landed at the shaft- bottom and I was relieved to find that it was well lit by electric lights. A tunnel curved away in the distance. My mining career had begun.

At the Stone Gallery exhibition in 1960, Cornish was introduced to Lord Lawson of Beamish, who was born in Whitehaven in 1881, moved to Boldon Colliery aged 9 and worked underground as a ‘trapper’ from the age of 12. Jack Lawson, a former miners’ leader, was elected to Parliament in 1919 as MP for Chester-le-Street and became Secretary of State for War 1945-46. He was also Lord Lieutenant of County Durham 1949-58. Jack Lawson and his wife invited Norman and Sarah to tea at his home one afternoon and a car was sent to collect them. After tea he suggested that he and Cornish have a chat in their front room and Jack Lawson produced a copy of his autobiography, ‘A Man’s Life’, which was a favourite of Cornish.

Lawson opened the book and read aloud the chapter describing the pit cage descending from the gantry, leaving Cornish with a much treasured memory. ‘A Man’s Life’ was a firm favourite on the bookshelves at Whitworth Terrace and it was humbly inscribed to Norman Cornish, miner artist, from the author Jack Lawson.

The book also delves into the challenges faced by miners: to overcome prejudice, the disrespectful treatment by officials and lost opportunities to continue their education. In one of the chapters, there is a reference to a poignant moment under-ground, and in total darkness, when pausing between strenuous activity, two of Lawson’s colleagues continue a conversation about the salient points in a specific Greek play.

Cornish worked hard as a miner but frustration crept in as he wrestled in his mind with the fact that a colliery was geared to coal production and not art appreciation.

The Gantry: Part 1

Cornish arrived cold and damp from walking over two miles in heavy snow to start work aged 14, at 2am, on Boxing Day 1933. He had no choice, and was denied the opportunity of continuing his education because he was the oldest in his family of five brothers and one sister.

There were over a hundred collieries and pits including quarries, brickworks and coking plants within a five miles radius of Dean & Chapter Colliery, at various stages or working, closing or dormant. The smoke and sounds of the railway engines hissing, coal trucks, colliery buzzers, and miners’ boots on the steps combined to create an industrial cacophony. The impact upon the environment and the men was pervasive.

He was offered a job as an underground datal ( paid by the day) lad and when he signed on the dotted line the official said in his deep voice: “You’ve just signed your death warrant son.” The pit was nicknamed locally ‘The Butchers Shop,’ owing to the number of accidents there. The records of 177 fatalities make for sober reading although there were no ‘disasters’ (officially five or more killed together, by gas explosion for example).In 1935 there were 2,135 men and boys working underground and 538 above ground. By 1937 the workforce was producing 3,000 tons of coal a day – a third of it machine - mined and the rest hand hewn.

On his first day he was given a lamp and a disc and moved out of the lamp cabin to be confronted by a flight of steel steps leading on to a gantry which crossed the mineral line. The gantry led onto the cage bank level which was at the opposite end of the gantry wheels and ropes. As the shunting engine passed below them, they became lost in a cloud of steam which reflected the arched window lights of the colliery like a cinema screen.

In his own words:

I went through the door and the first thing I saw was the gantry scene. The men were there with their orange oil lamps and they looked like fireflies. Then I saw a mass of steel railings, steps, girders and steel wires. I thought it looked like a great steel spider’s web and when I saw the colliery behind, I thought it was like a giant big spider – moving towards us and then going to drop us down a great hole.

The picture is about feeling – what I felt and saw as a boy.

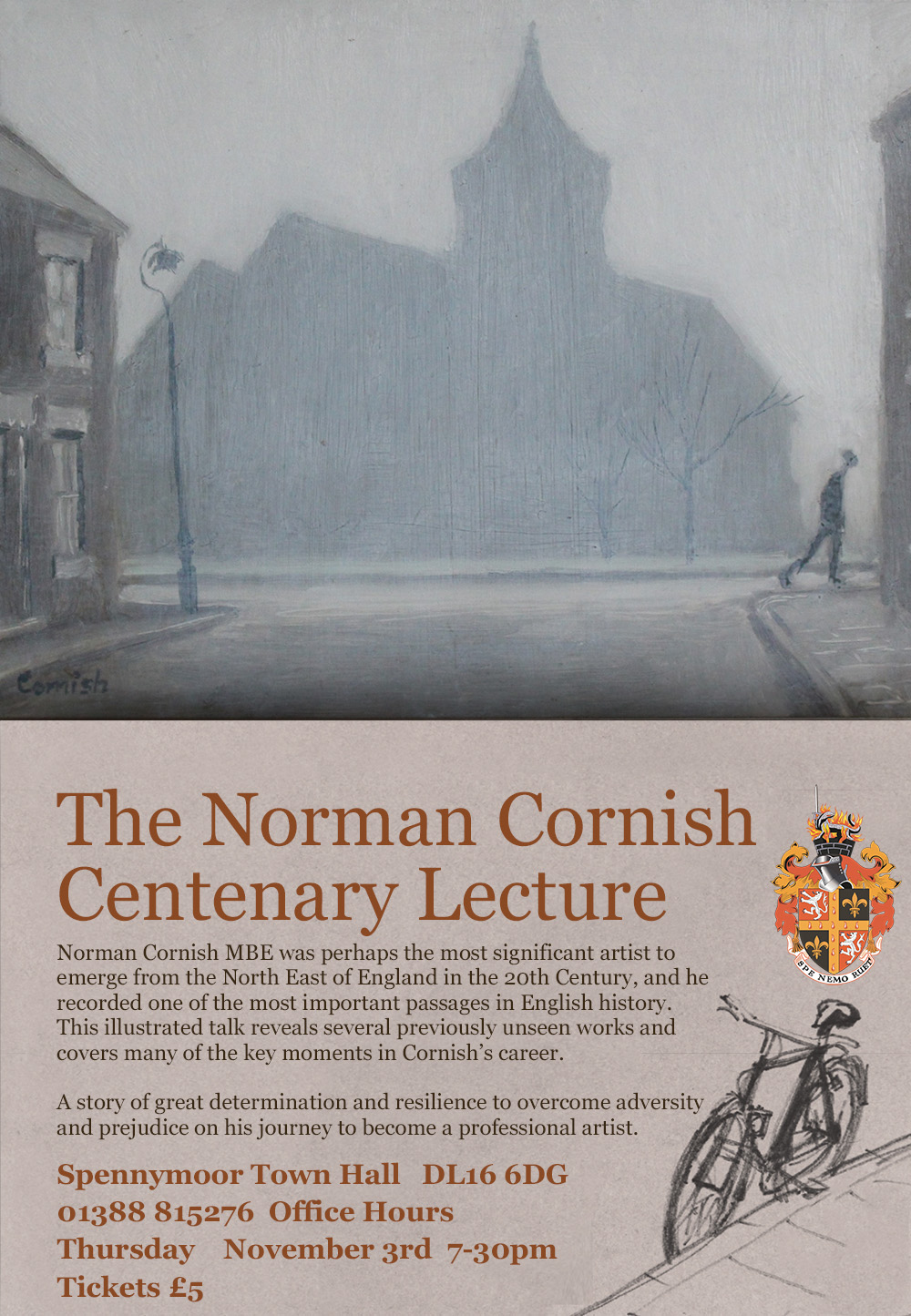

Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Centenary’ lecture 1919-2019

Spennymoor Town Hall 7-30pm Thursday November 3rd 2022 7-30pm

An illustrated talk by Norman Cornish’s son – in law Mike Thornton

Tickets £ 5 From Spennymoor Town Hall Reception and also available via telephone in normal office hours Monday to Friday - 01388 815276

Norman Cornish MBE was perhaps the most significant artist to emerge from the North East of England in the 20th Century, and he recorded one of the most important passages in English history. Revealing predominantly unseen works, the talk covers many of the key moments in Cornish’s career including commissions such as The Durham Miners’ Gala Mural in 1962, Cornish in Paris in 1967 and two commissions for The Port of Tyne Authority in 1982. The talk also includes images of life in his family home from the 50s and 60s in Spennymoor, which has been recreated as part of the 1950s town at Beamish Museum.

It is a story of great determination and resilience to overcome adversity and prejudice on his journey to become a professional artist.

Please arrive early. Doors open from 7pm.

The Bob Abley Gallery including the current ‘Coming Home’ exhibition and Norman Cornish studio will be open between 6pm and 9-30pm

Free parking behind the Spennymoor Town Hall

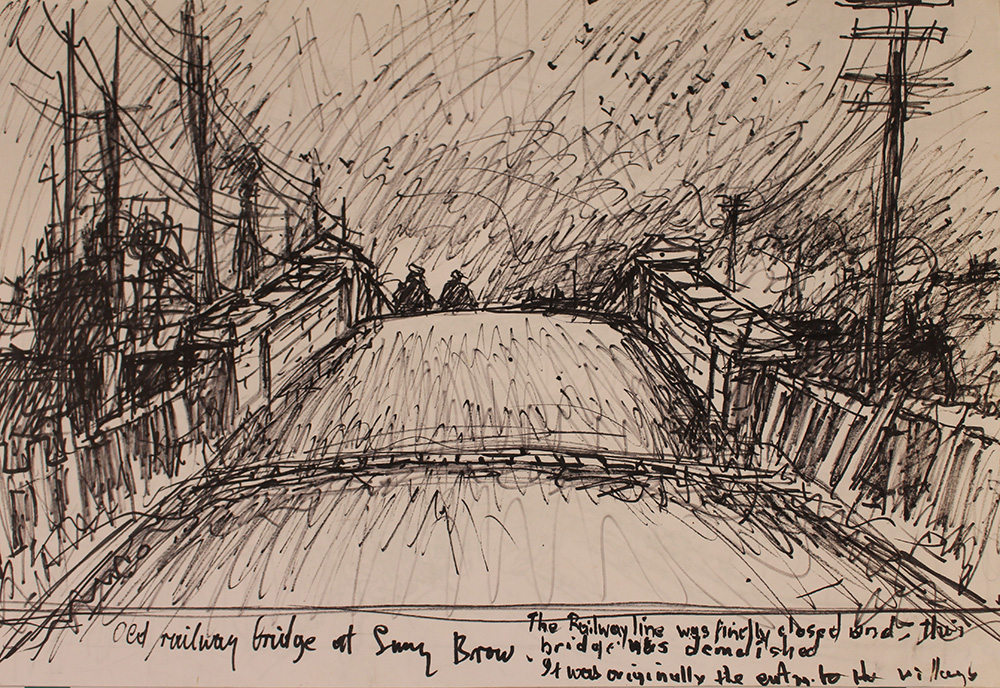

Behind The Scenes: The Bridge at Sunnybrow

Cornish occasionally visited other villages in County Durham as well as places of interest across the region. The Pit Road theme was interpreted in several locations and the huge number of collieries provided other opportunities to develop this iconic theme which impacted the lives of thousands of other miners and their families.

Unable and unwilling to learn to drive, many places in the county would have been inaccessible to Cornish had it not been for his good friend Jack Savage who drove him in his Morris Minor to a number of villages and collieries.

In October 2011, Jack Savage’s daughter, Anne Wood CBE (creator of The Teletubbies and a Children’s TV producer) featured on BBC Radio 4, Desert Island Discs. During the interview, she spoke with warmth and affection about her family roots in Spennymoor and the influence on her life of Norman Cornish MBE 1919-2014.

Sunnybrow was a small colliery near Hunwick in the Wear Valley. The railway line finally closed in the 60s and this bridge was demolished. Originally it was the entrance to the village.

In his own words:

One wonders with the passing of time, when no present-day type pitheads actually exist, if pictures of them might one day be thought of as picturesque and as socially significant as old windmill pictures. They are both dominant shapes in the skyline; they both make big angular shapes against the sky; they both have big revolving parts. Also they both of them tend to have workers’ houses built around them.

The Bridge at Sunnybrow is featured in the book, Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks, in the chapter devoted to Mining Scenes. The other chapters show the development of his work in Street Scenes, Bar Scenes and Observations of People. Copies may be purchased by visiting www.normancornish.com

More Articles...

- Behind The Scenes: The Bridge at Sunnybrow (2)

- The Crowded Bar

- The Pony Putter

- A Slice of Life

- The Local Collieries

- A Bedroom Studio

- Realism to Abstraction

- ‘Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Centenary’ lecture 1919-2019

- Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks at Scarth Hall

- The Unseen Works - ‘Did you know?’