Latest News

Community Arts: Inspired by Norman Cornish

Norman Cornish started work at Dean & Chapter Colliery at 2am on Boxing Day 1933 aged 14 years. He was already aware that he had an emerging interest and skill in drawing and he was later excited to learn that a ‘Sketching Club’ was part of the new Spennymoor Settlement. However, he was disappointed when he asked to join because he was rejected and told to return when he was a year older. He waited patiently and twelve months later he was allowed to join and the rest is history!

The modern day equivalents of the national ‘Settlement movement’ are community arts centres, arts clubs or community arts projects and an excellent example may be found in Sunderland at Southwick REACH’s :‘Together in Southwick’ Project

Southwick REACH’s current project, Together in Southwick (funded by the Lottery Community Fund) evolved through a culmination of many smaller projects including a Covid-19 Recovery Programme which reconnected isolated members after the lockdown eased. There was a real hunger for regular workshops to continue. The Together in Southwick programme has provided regular creative workshops for the local community where members have learned many new skills and techniques to create some wonderful artwork. The group have enjoyed visiting various cultural venues and exhibitions including, Beamish Museum’s 1950s Town where they enjoyed exploring the home of the Cornish family and Norman’s home studio. It’s rewarding to see participants expressing themselves through creativity as well as connecting with peers and forming new friendships. Group members regularly feedback the benefits of taking part and as a result, we know it is vitally important to continue this valuable therapeutic process to combat loneliness and isolation through connecting regularly and creating with others.

One member who supports her husband living with dementia said:

“REACH –Research, Education, Arts and Culture Home gives us the opportunity to both enjoy time together in a safe, friendly, welcoming place. It helps us both to have some me time and express ourselves through art. Art and Reach isn’t just about what we do, it’s also about being part of the group and support we can offer one another, it’s so much more and has been a lifeline for us.”

We are grateful to The National Lottery Community Fund for supporting Together in Southwick.

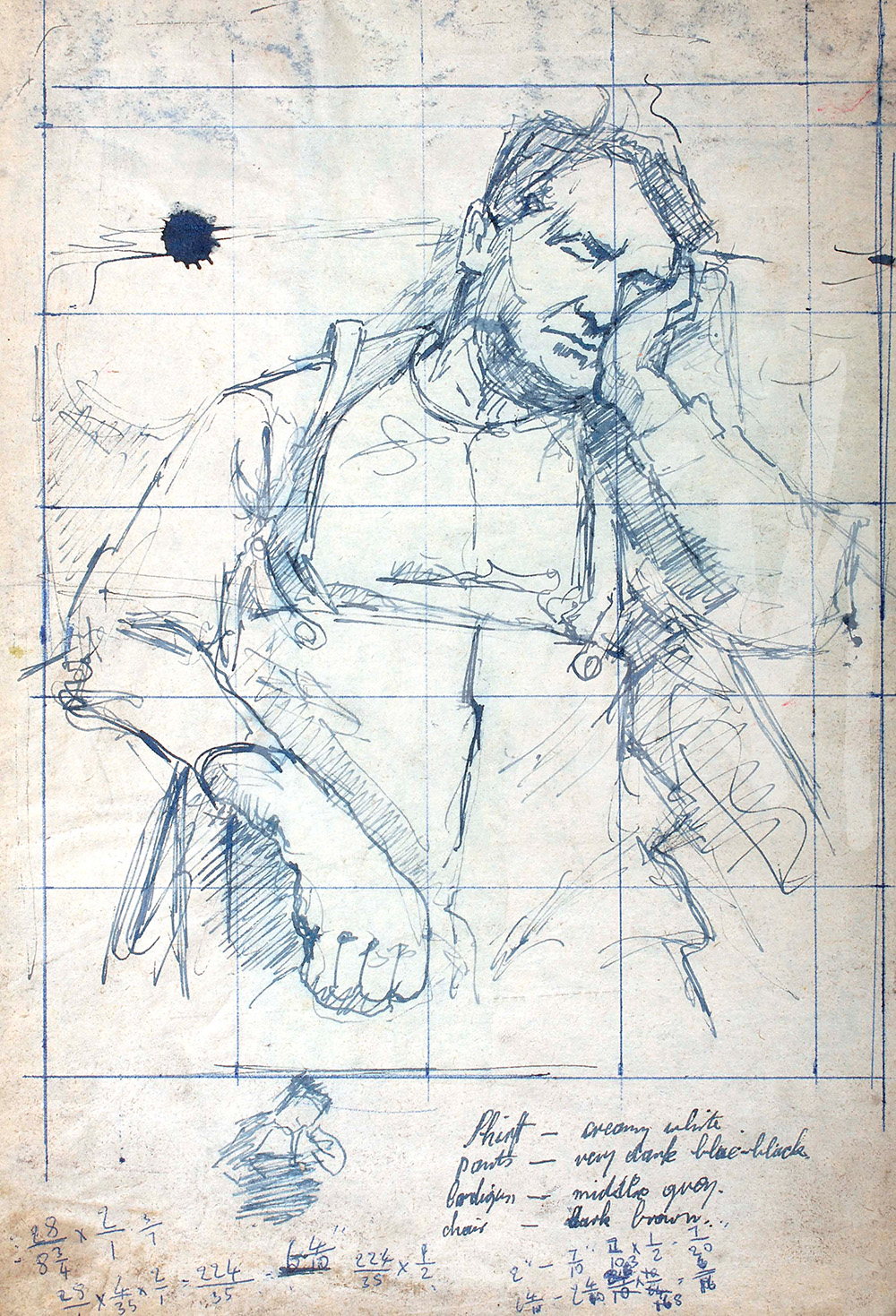

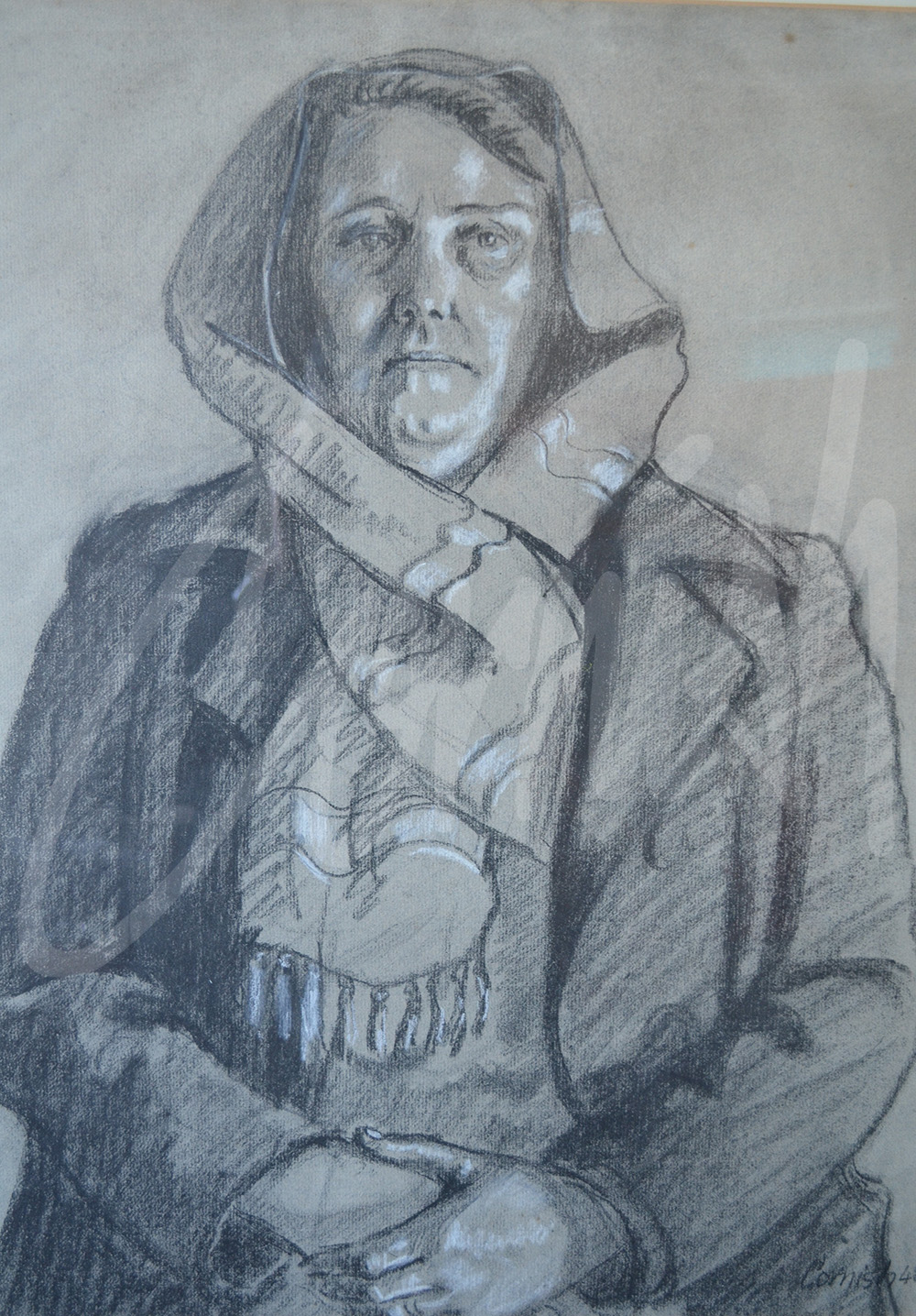

In their recent exhibition ‘Southwick Streets’ members also exhibited the Norman Cornish style sketches and paintings they created whilst studying the work of the artist and learning new skills at the beginning of the project.

The Spennymoor Settlement Sketching Club provided mutual support to the members during an equally challenging era and they later developed a strong regional and national reputation.

Congratulations to all of those involved in the project guided by Lyn Killeen, Southwick REACH Artistic Director.

Vincent van Gogh

As a member of The Spennymoor Settlement Sketching Club, Norman was able to borrow authoritative books about famous and influential artists. Men of talent but limited resources were thus able to access the outside world via the medium of print.

In March 1950, an Arts Council exhibition in Anfield Plain displayed many reproductions of images by van Gogh. The exhibition also included works by members of the Sketching Club, including eight original works by Norman Cornish.

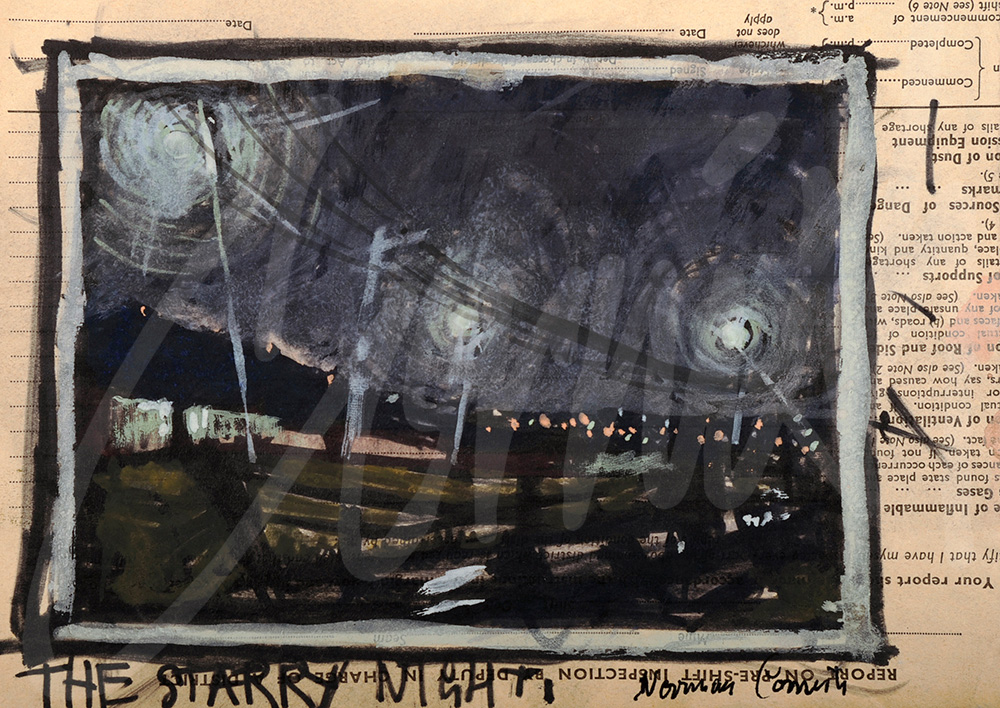

Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night was painted from memory, in daytime, during a difficult period in his life. It was 1889 and he depicted the view from the east- facing window of his asylum room at Saint-Remy-de Provence just before sunrise, with the addition of an imaginary village.

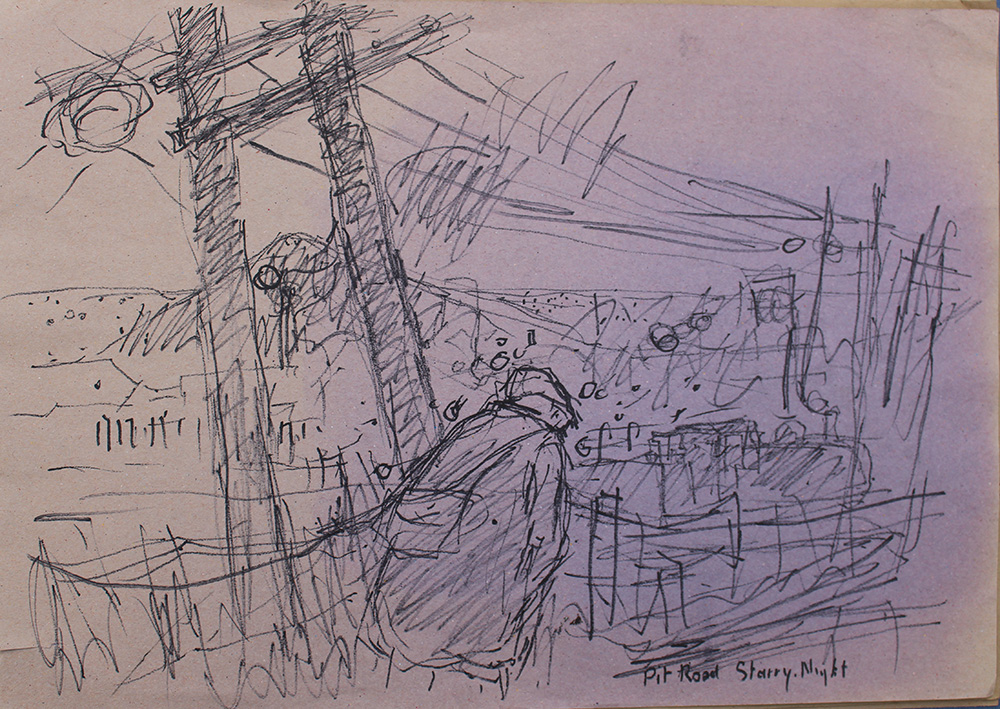

Norman Cornish’s Starry Night is experiential, based on walking the pit road every day, for some 30 years or more, at varying times of the night and day, and in all seasons of the year. The Pit Road is perhaps Cornish’s most iconic image throughout his career, often repeated, with numerous variations. The journey to Dean and Chapter Colliery was three miles each way that he travelled along with hundreds of other men.

Talking to a group of children many years ago, Cornish described his experience on the pit road:

‘A gust of wind blew raindrops into my eyes and my vision became a blinding flash of light. When my eyes cleared, I began to see the scene differently. The lights looked like stars in the sky.’

Norman Cornish 1973-2013 Academic success and national acclaim

This final period in Cornish’s professional career evolved into something more than just exhibiting to satisfy the strengthening and deepening emotional attachment expressed by so many of the admirers of his work.

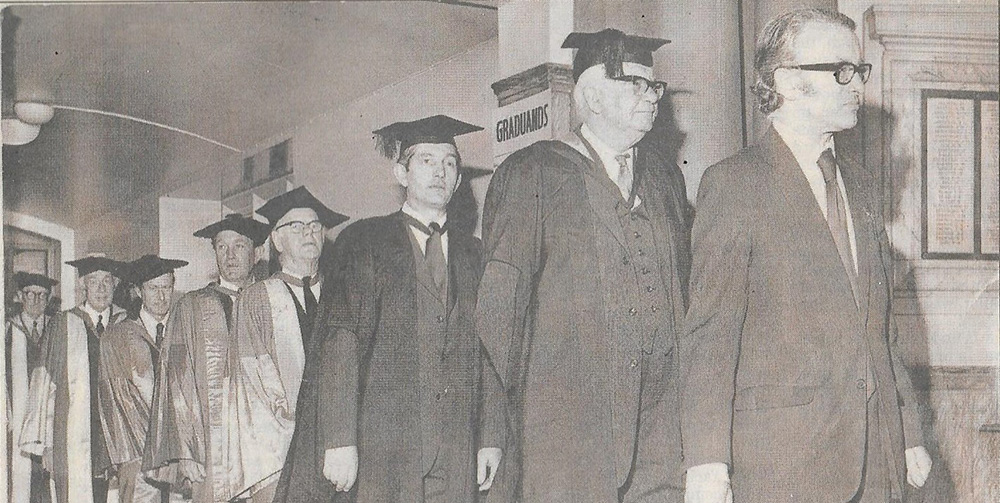

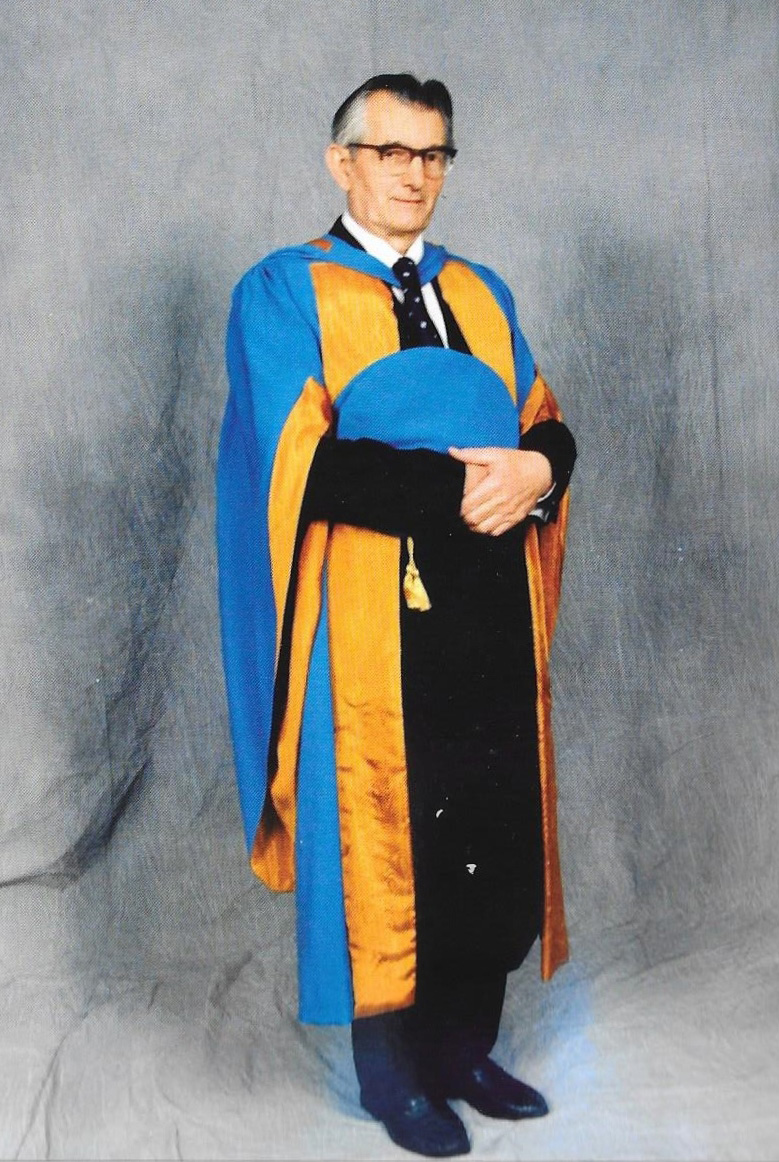

In May 1974 he was awarded an Honorary Master of Arts by Newcastle University, and further academic awards were to follow.

In 1995 Cornish was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Civil Law by Northumbria University. A second Honorary Doctorate of Arts from Sunderland University was awarded in 2012, although he was too frail to collect the award in person.

The Permanent Collection at Northumbria University received a donation of ten paintings by Cornish in 1997 as part of their ‘New Acquisitions’ along with works from Lucien Freud and Walter Sickert.

Cornish first met Prince Phillip when he opened the new County Hall in 1963 and HRH was to return to Durham in 2002 along with HM Queen Elizabeth during the Queen’s Golden Jubilee celebrations. Durham Castle was the venue for lunch accompanied by the Chancellor of Durham University Sir Peter Ustinov.

The BBC ‘Inside Out’ programme featured Cornish and Lowry in 2006 and later that year one of Cornish’s paintings featured in the series ‘Flog It’.

Unable and unwilling to travel to Buckingham Palace due to declining health, Cornish was a reluctant recipient of an MBE in 2008 and the Lord Lieutenant of County Durham arranged to present the award to Cornish at his home at 67 Whitworth Terrace, Spennymoor.

Cornish belonged to a generation denied the opportunity of continuing with education from an early age. Working class artists were deemed to be ‘Sunday Painters’ and there was an assumption of naivety of such artists by the Arts establishment, because of their occupation, as well as implied political associations. In 1939 He was denied the opportunity to attend the Slade School of Fine Art in London because he was in a ‘reserved occupation.’ Subsequently he had to overcome prejudice and resentment by some students and some colleagues when he taught part-time at Sunderland Art College in the late ’60s - because in their eyes - he lacked an academic background. Despite the obstacles to success, a rare talent emerged in the post war years and a burgeoning national reputation.

Parents: Jack and Florence

Norman Cornish was born in Oxford Street on the 18th of November 1919 and moved later to Bishops Close Street, adjacent to the gasworks, ironworks and railway embankment at the end of the street. Cornish shared the stone- terraced house with his parents Jack and Florence along with his younger brothers Tom, Jack, Jim, Billy, Bob and sister Ella.

The Times newspaper referred to Spennymoor as a place without a future, immersed in despair, desperation and futility. Housing conditions were primitive, no bathroom, gas lighting, and an outdoor earth closet. Epidemics of diphtheria, smallpox and scarlet fever were rife amongst the children.

In his autobiography ‘A Slice of Life,’ Cornish recalls that he only ever saw one book in his childhood home. Cornish’s father Jack was unemployed for some time during the Depression but eventually gained employment at Dean and Chapter Colliery. One of his father’s friends tried to persuade his father to allow Cornish to continue his education, but at the age of 14 he reluctantly took his young son to his colliery to get him ‘set on.’ He later started work on Boxing Day 1933, after walking three miles to the pit in the snow.

Florrie would always be busy seeing to the six boys and daughter Ella. Making clothes, ensuring meals were available and a plentiful supply of hot water for washing. The daily commitment to keep the family together and maintain some dignity must have been exhausting.

Cornish eventually gained permission to join the Sketching Club at The Spennymoor Settlement which he later described as, ’like crawling into a warm woolly sock after the pit’.

As his interest and skill in drawing developed, via the ‘Sketching Club’ at the Spennymoor Settlement, the advice from Bill Farrell to draw and paint what he knew became more significant and in his own words: ‘ Most of the members were steeped in landscape tradition but I’d rather draw things I saw in my house, like my mother preparing a meal or my father washing after coming back from the pit’.

Despite the harsh conditions he was later able to acquire a deep knowledge, of not only art history, but also literature and music. Cornish made the most of opportunities denied in his early years to become ‘well read’ and he could quote with confidence from Dickens and Shakespeare as well as enjoying his love of Classical Music and Opera.

The Port of Tyne Commission Part 1: Roll-On Roll-Off

Norman Cornish’s work is traditionally associated with the life and times of communities across the region. His work can also be considered as an invaluable social record and archive of the people and places of his era as he emerged as a leading British artist. His traditional paintings represented a time and places which were disappearing, although he frequently re-visited many themes, constantly discovering new ways to interpret his favourite subjects. During the 70s, Cornish’s first academic recognition followed with the award of an Honorary Master of Arts Degree from Newcastle University in 1974.

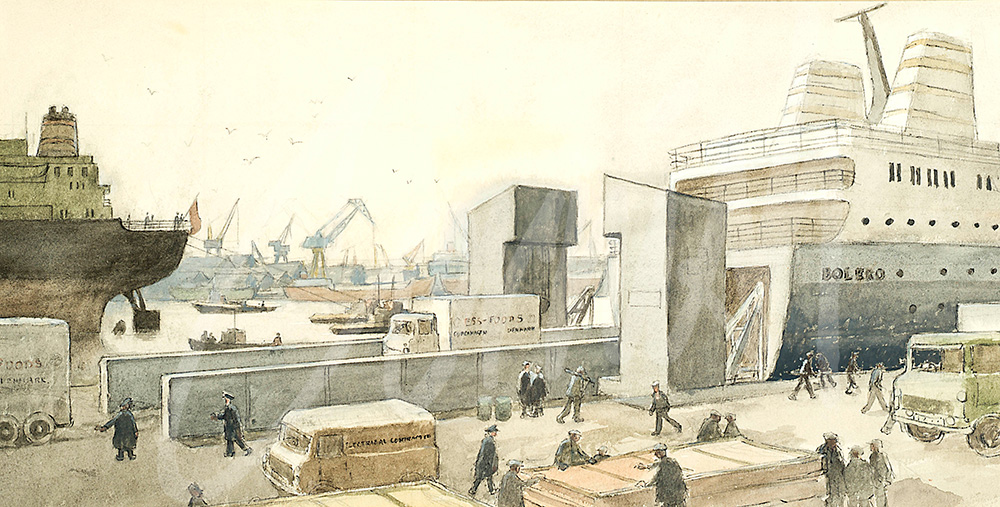

In 1980 he was informed by his agent that The Port of Tyne Authority would like to commission him to capture, in oils, their recently completed Roll-On Roll- Off ferry terminal at North Shields.

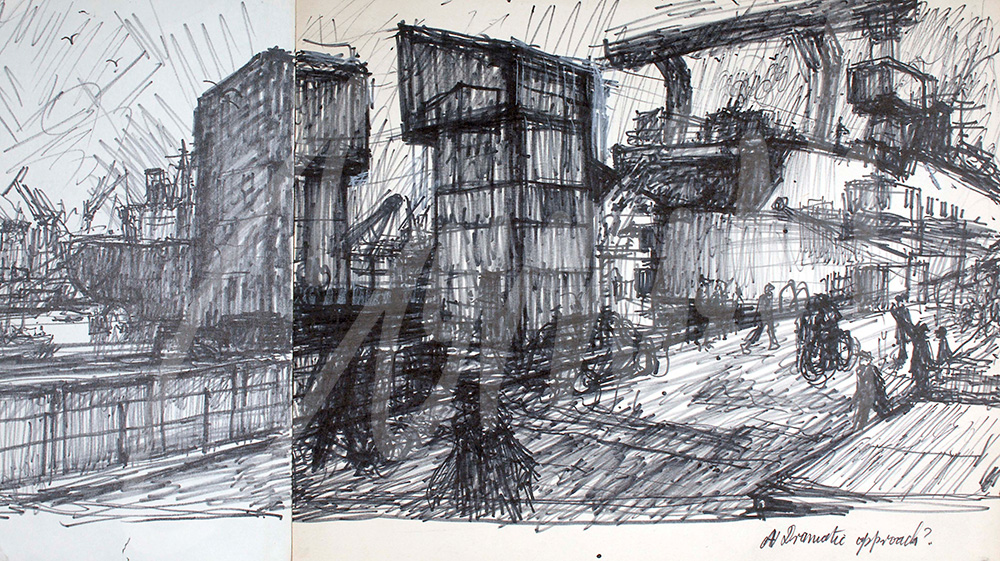

This prestigious commission enabled a departure from his traditional subjects, but also became a landmark in his developing career as a professional artist. Unable and unwilling to learn to drive, Cornish travelled by bus from Spennymoor to Newcastle, and onward to North Shields on several occasions to ensure that his record of the area, equipment and facilities was a factually accurate representation of the facility. The final painting, oil on canvas measuring 120cm x 155cm was the culmination of several smaller versions in watercolour, pastel and Flo-master pen. There are approximately 20 previously unseen preparatory drawings completed during his research.

The final version was exhibited for the first time in the retrospective exhibition at The Bowes Museum during his centenary year.