Latest News

A Good Drying Day:

‘They that wash on Monday have all the week to dry.’ This Victorian advice on housekeeping routines set in stone the idea that Monday should be wash-day so that everything could be dried, pressed, aired and folded well before Sunday, the day of rest and clean clothes. A typical Monday in many homes during the 1950s would have seen a small kitchen full of laundry at different stages of washing, and hot water was provided by various means. Some homes had a boiler heated by the coal fire but at 33 Bishops Close Street a gas burner underneath a metal tub provided the hot water. A ‘blue bag’ was added to make the whites ‘whiter.’

Washing machines were a late arrival in Spennymoor in the 50s and ‘poss tubs’ were in use in most homes and handwashing was the norm.

A clothes horse was an essential item in every home for drying indoors around the fire, although dampness pervaded the atmosphere when drying outside was impossible. A good drying day meant that the back yard or back lane was full of washing ‘hanging out to dry,’ supported by a ‘clothes prop’ fashioned from a single piece of wood with a v-shaped notch cut at the end of the prop.

There were many obstacles within a short distance of the back gate in Bishops Close Street including a slag heap, ironworks and steam engines pulling coal trucks at all times of the night and day. Any thoughts of playing cricket or football in the back lane on washing day quickly evaporated when met with short sharp reprimands from mothers, although a skipping rope was slightly more acceptable. The writer vividly recalls (Tyneside, aged 7yrs) with the lads, hearing the words, “if that ball goes anywhere near my washing you’ll all be skinned alive and hung out on the washing line to dry!”

All of these memories, including the delivery of coal in the back lane were also recorded by Cornish and his work continues to provide a remarkable slice of social history typical of many communities throughout the UK.

The ‘poss tubs’ have all gone, along with the clothes horses, and good drying days are no longer essential. This social change also signalled the demise of the clothes peg which was probably one of the few items to escape the attention of Cornish in his sketchbooks.

John Peace Exhibition: Tyne and Tide - South Shields Museum and Art Gallery

EXHIBITION CLOSES ON MAY 7th

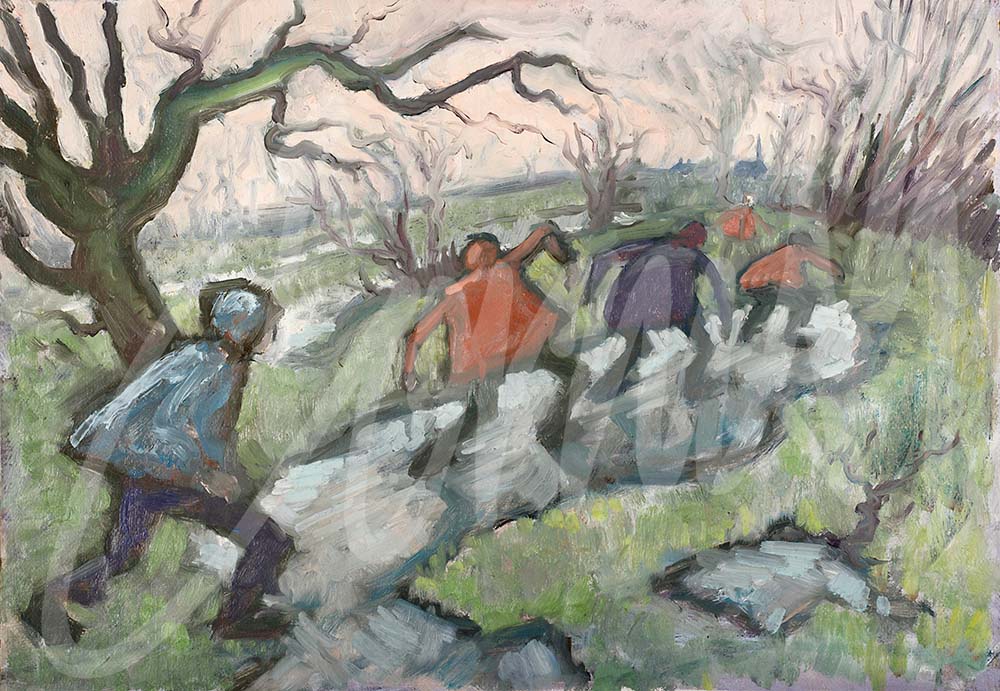

Last year we were delighted to feature an article on behalf of the family of John Peace who have been working very hard to establish the Back Catalogue of his extensive range of work held in many public and private collections in the UK. Cornish and Peace were contemporaries who exhibited together during the 60s and 70s at The Stone Gallery in Newcastle, along with many other leading British artists.

John was from Lemington and taught at Sunderland Art College at the same time as Cornish who worked there from 1967 for a few years after leaving mining. John Peace’s work records the NE from a different perspective and may be viewed at www.johnpeacepaintings.co.uk

John Peace studied at the South Shields School of Art from 1949-51, then at Leeds before gaining a place at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. He had a lifelong career in painting, as well as teaching art, and produced hundreds of paintings many of which captured the landscape and aspects of social life in the changing region around him. It was a career deeply influenced and shaped by his time in South Shields.

This major exhibition opens on November 13th until May 7th 2022 and brings together a significant selection of some of his finest work. It focuses on landscapes, many depicting the region’s coast and rivers, as well as the area around Lemington, where he spent most of his life, and includes paintings of South Tyneside and Sunderland. Landscape was Peace’s main interest but he also produced many paintings of other subjects and a section of the gallery will present examples of his portraits, still lifes and scenes of family life.

Above all Peace was interested in capturing the effects of light. His compositions were often simple and painted with a narrow range of colours to create a powerful striking view of the world around him. Tyne and Tide provides a unique opportunity to see many of his best paintings including those owned by his family, alongside a number of loans from private collections.

An exceptional exhibition.

Convicts and Slaves: Symbolism

Between 1708 and 1951 over 2,000 men and boys were killed in disasters at coal mines in Durham and Northumberland. Miners and their families throughout the region will have been aware of these tragedies and it is more than likely that the accidents and their consequences must have been traumatic for communities with associated erosion of well-being and increased anxiety.

On a daily basis men and boys would arrive at work not knowing what awaited them working underground, but Cornish was able to provide a simple summary, often developed into pictures which represented conditions underground.

‘The dangers of gas, stone falls, the darkness and restricted space, were all to shape these men into industrial gladiators.’

Cornish commented that the men were spoken to like ‘convicts’ and treated like ‘slaves.’ An observation from an artist who was a sensitive and deep thinking intellectual.

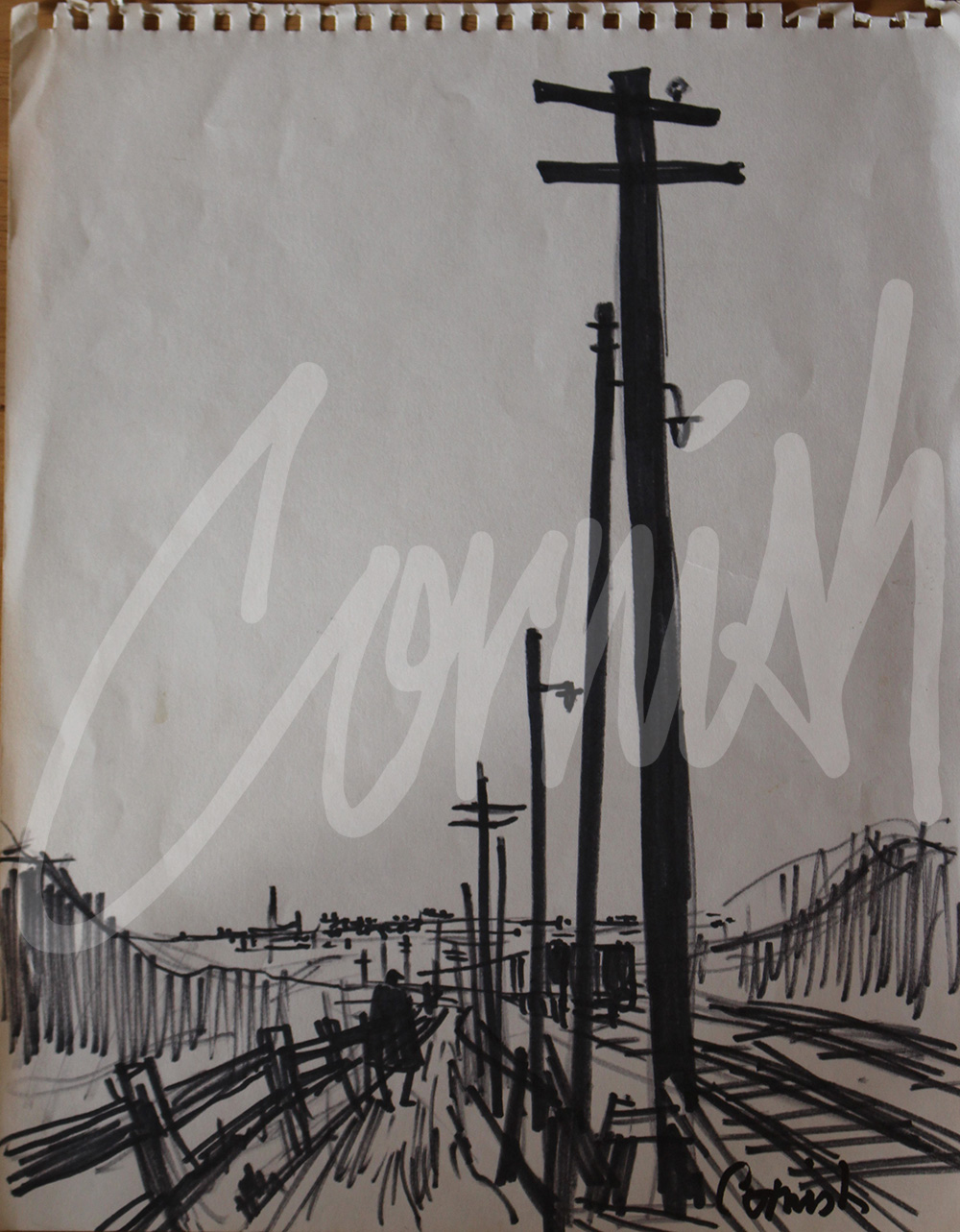

The journey to and from work along the ‘Pit Road’ was also a time of personal reflection and it is not surprising that this journey of three miles, and the immediate environment was also to impact upon his thoughts. The iconic images of the Pit Road paintings will be familiar to those who enjoy his work, which evokes strong memories of past generations who shared these experiences.

‘I have always been obsessed with shapes, or at least shapes which can be symbolic of things beyond themselves. A telegraph pole can be thought of as a totem pole to man’s technology.’

‘All these poles thrusting up at the side of the road- they’re like a series of crosses and sometimes I look at them as I walk along and they’re not telegraph poles anymore- they are crucifixes and on every one of them there’s a miner hanging crucified.’

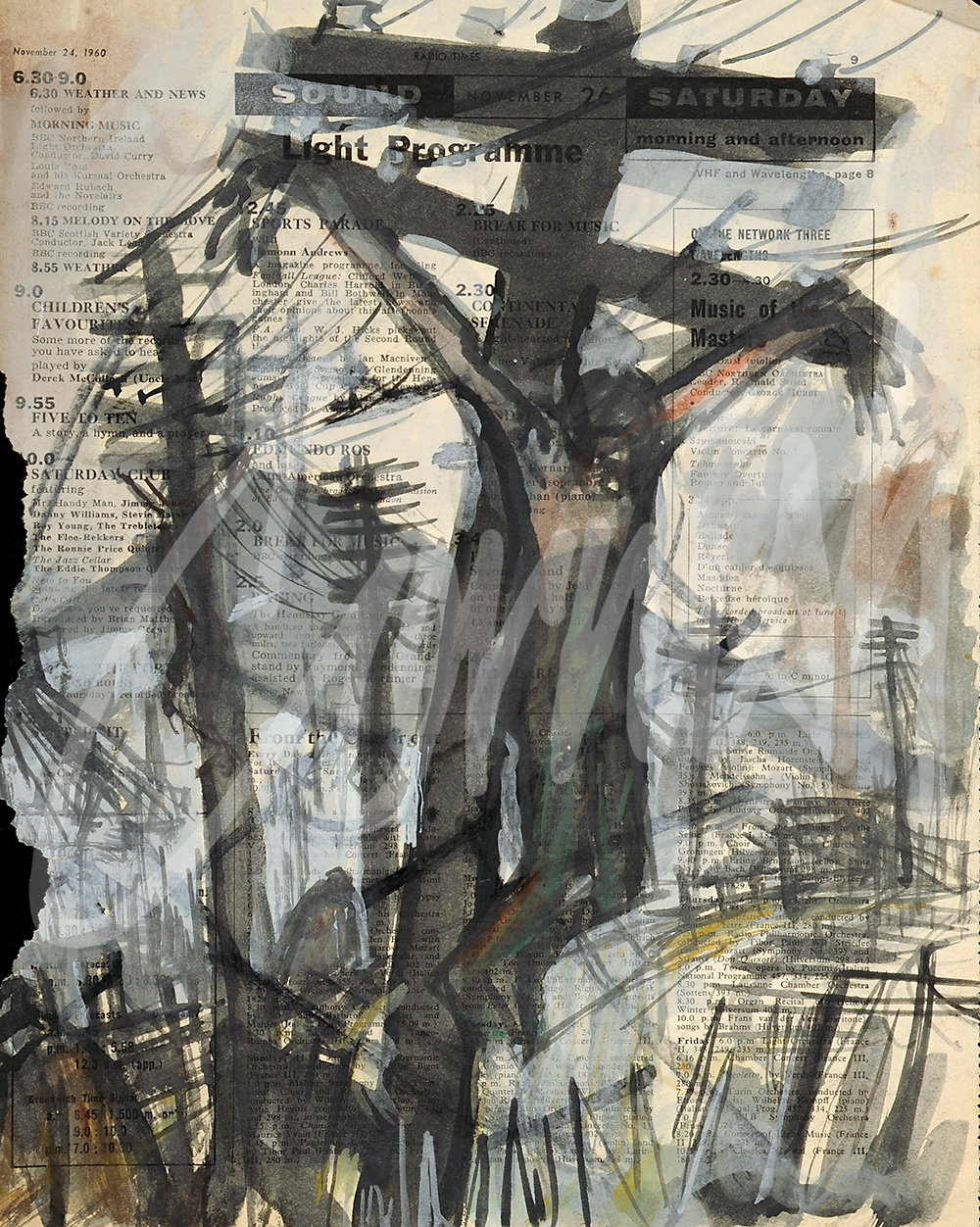

For over a thousand years artists around the world have used symbolism to convey a hidden or underlying meaning in their work. A crucifixion has appeared in art and popular culture in many forms including works by Rembrandt, Salvador Dali and Barbara Hepworth. Other examples have occurred in classical music, television, film and in the 1970 rock opera ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’ which ends with Jesus’ crucifixion.

The version by Cornish was clearly inspired by his perception of his circumstances and utter frustration as he quickly transferred his thoughts to a sheet of paper ripped from ‘The Radio Times’ November 24th 1960.

The Art of Drawing

The ability of an artist to sketch and draw with speed and accuracy, to capture a moment in time, is fundamental towards future success and forms the basis upon which all else follows.

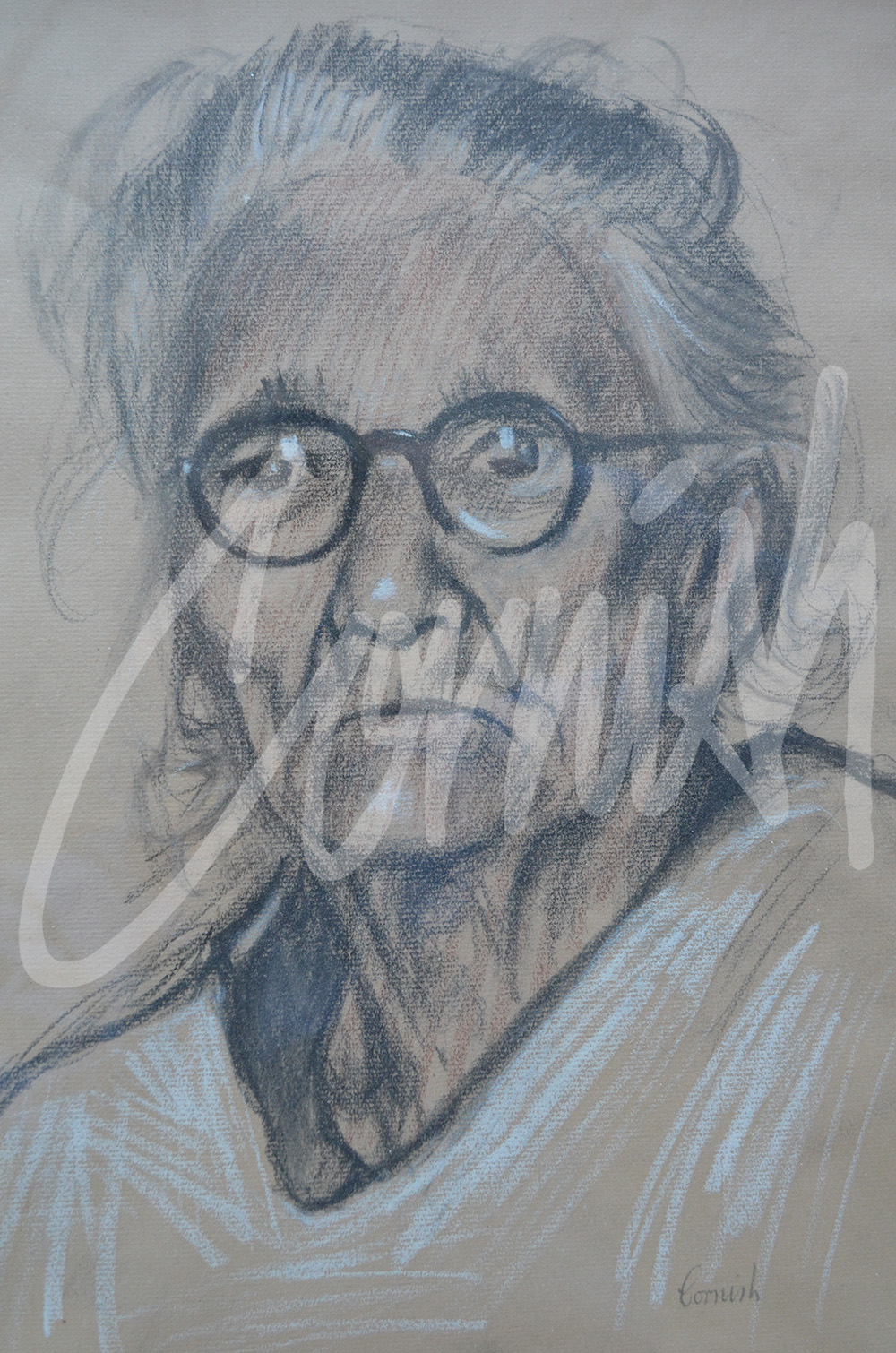

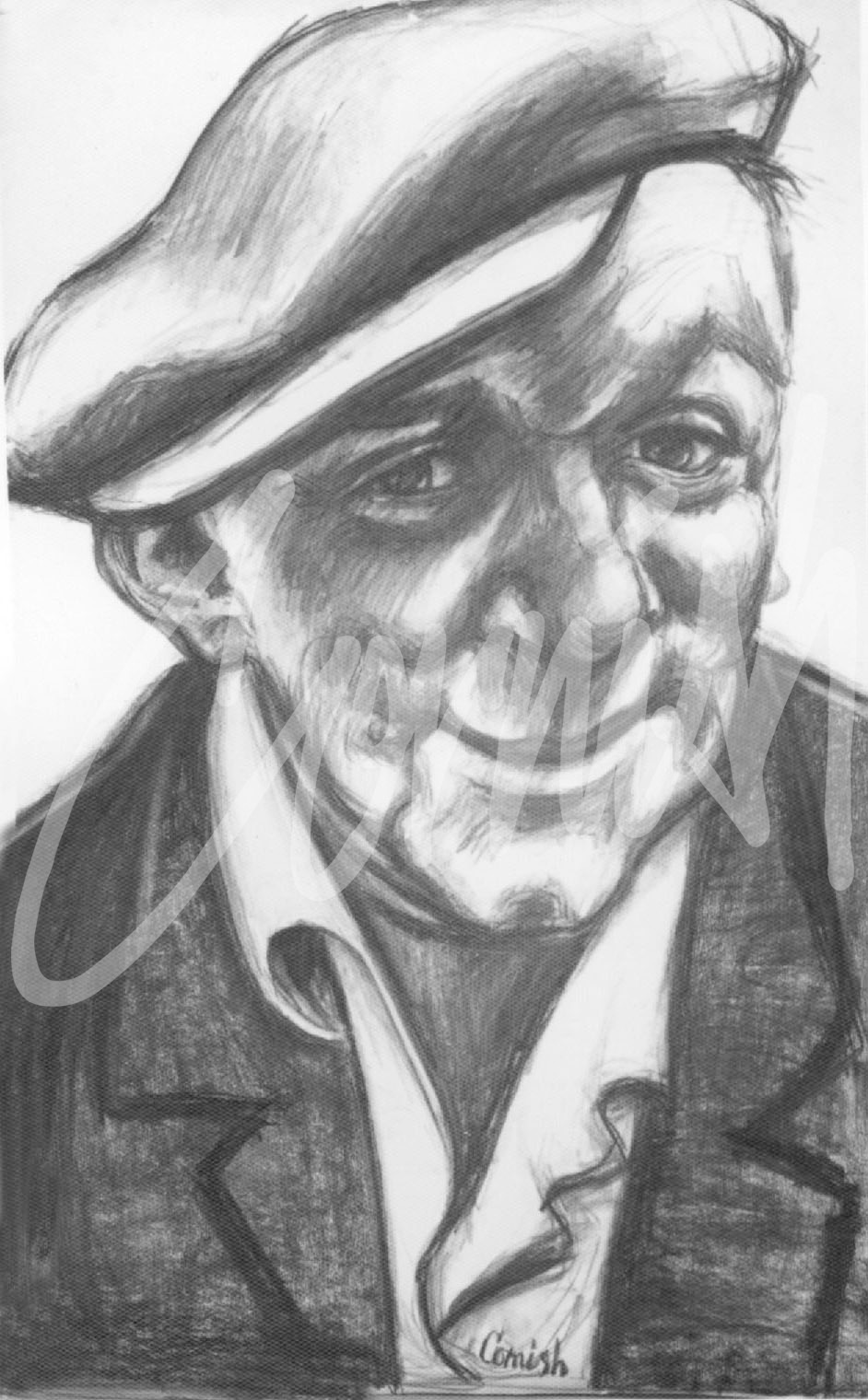

Cornish joined the Spennymoor Settlement Sketching Club shortly after his 15th birthday in 1934. He had previously been ‘turned away’ because he was too young. Annual exhibitions at the Settlement were a notable feature and in his 1936-37 report Bill Farrell noted that ‘the Settlement exhibitions are being considered of some importance in the art world and being visited by people from all over the British Isles’. Cornish was singled out for particular note in 1939: ‘Some new members have joined all of whom show promise, but one young man in particular has shown a distinct talent for portraiture in oils, We expect much from him and only regret our inability to send him to one of the larger Schools of Art. A talent will not be wasted but it will take longer to come to fruition. Norman Cornish has painted portraits of his father and mother and of his grandmother, a fine old Durham woman with a characterful face which, if painted by a Rembrandt or Frans Hals would tell the story of the Durham Miners wives for all the world to see.’

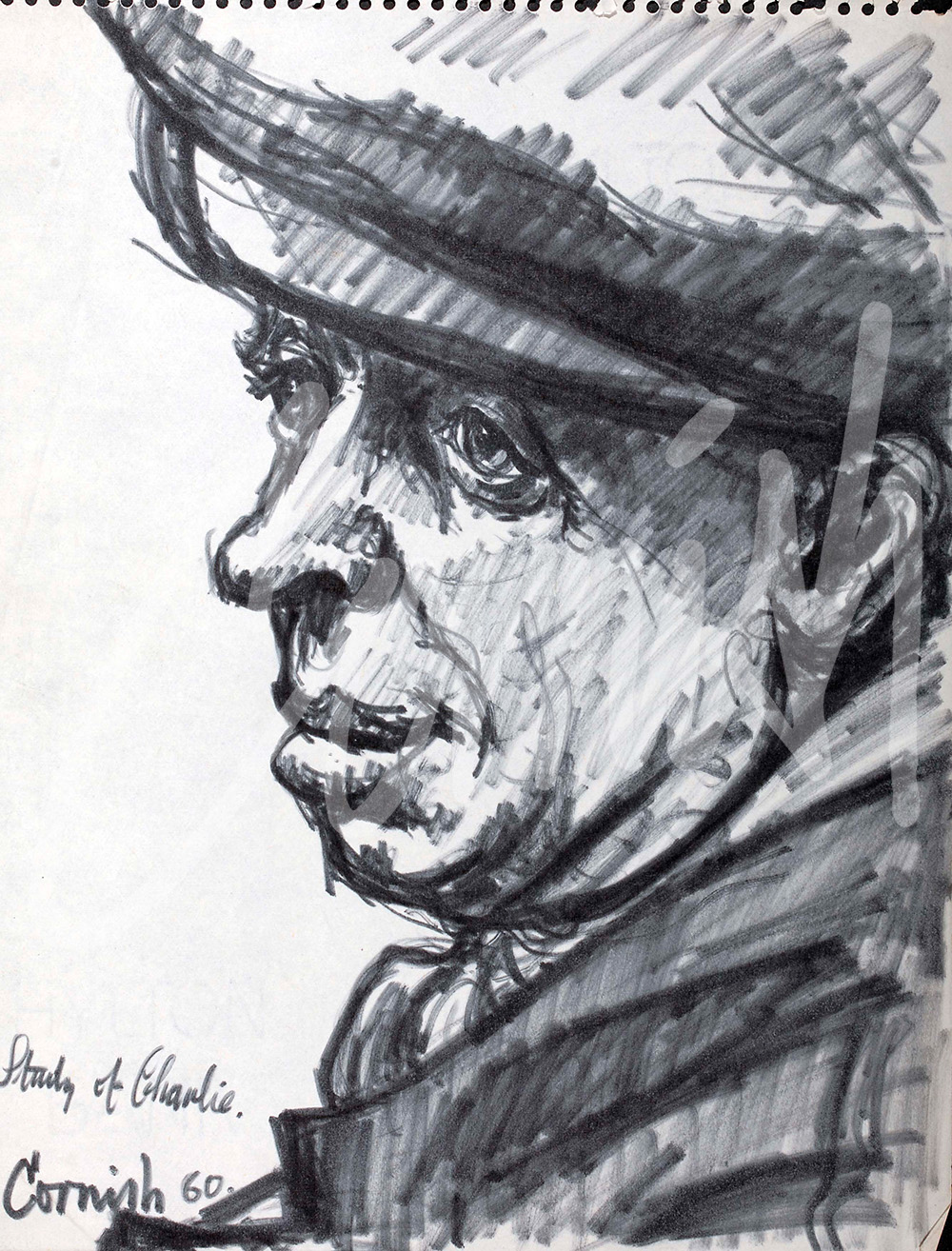

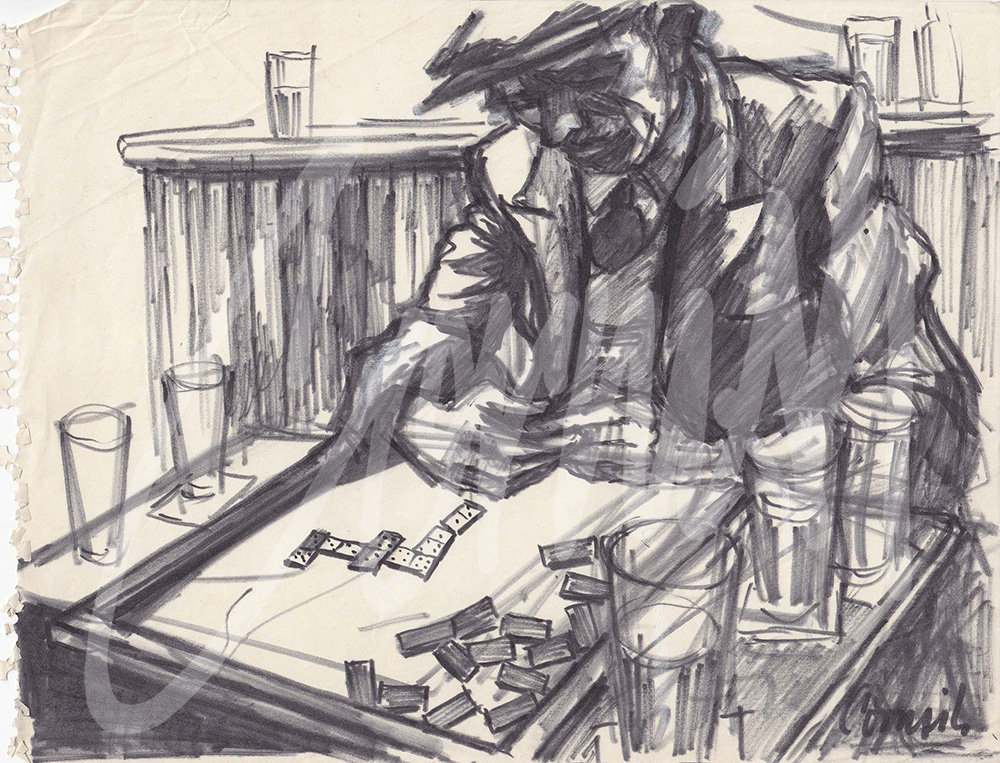

This remarkable portrait of his grandmother was drawn in charcoal and chalk when he was only in his late teens. This period of his life and career was particularly significant in the development of his sketches and carefully observed drawings although he was limited in his choice of medium. Eventually his favourite medium became the Flo-master pen, a forerunner of the modern fibre-tipped pen. However, he was unable to acquire a Flo-master pen until he received a gift from Ted Harrison in 1951 at a conference at Wallington Hall in Northumberland where they were both guest tutors. The pen could be re-filled and nibs inter-changed as required. The width of the strokes and intensity of the ink could be controlled by applying pressure, or a light touch. Accuracy was important as the indelible ink dried on the surface of the paper within two seconds. Tiny black dots are sometimes visible on some drawings, as he touched the paper with the pen to stimulate the flow of ink. Cornish’s wife, Sarah, adapted his jacket with a ‘poacher’s pocket’, large enough to hold his sketchbook and pen so that wherever he went the sketchbook and pen were always immediately accessible.

There were 37 pubs in the Spennymoor area during Cornish’s era and the men who were often his workmates (Marras) became an irresistible subject for him as an artist, but not just any artist. As an underground miner he was not an outsider as, for example, was L S Lowry, a rent collector in Salford. Lowry was an outsider looking in on his subjects while Cornish was accepted in the community he recorded, despite his unusual activity of sketching in the pub. In a world where men could be ostracised if they did not drink, the beer in Cornish's glass gave him the passport to be able to share, observe and record that communal life. Because he could blend in this gave him the opportunity to produce so many character drawings of his subjects in conversation, playing dominoes, darts or occasionally deep in thought.

During a visit by Andrew Festing to examine Cornish’s drawings a few years ago the former Head of British Painting (Sothebys 1977-81) and President of The Royal Society of Portrait Painters 2002 -2008 commented :

“The quality of Cornish’s drawings is as good as any other artist in history.”

The Adventure Alternative:

Many people have a basic desire for some form of adventure and excitement in their lives that can be satisfied in different ways. For some it may be the thrill of watching an exciting film or TV drama, or a natural phenomenon such as the recent violent storms. Others seek the thrill of more dangerous activities not knowing the outcome. But thrilling experiences are no longer the preserve of a limited number of participants.

Working underground in coal mines or other industrial environments was a daunting experience for those who had little choice in employment. It was hardly surprising that the Youth Hostels Association had its roots in Northumberland during the 1930s to provide basic accommodation to help young people of limited means to enjoy the country side.

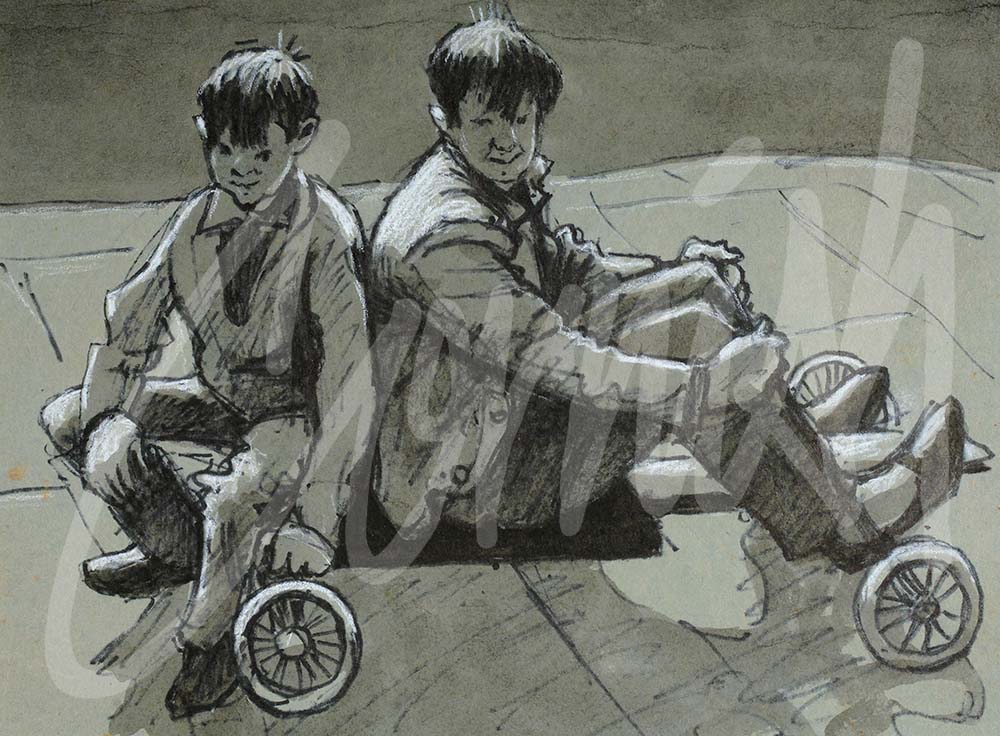

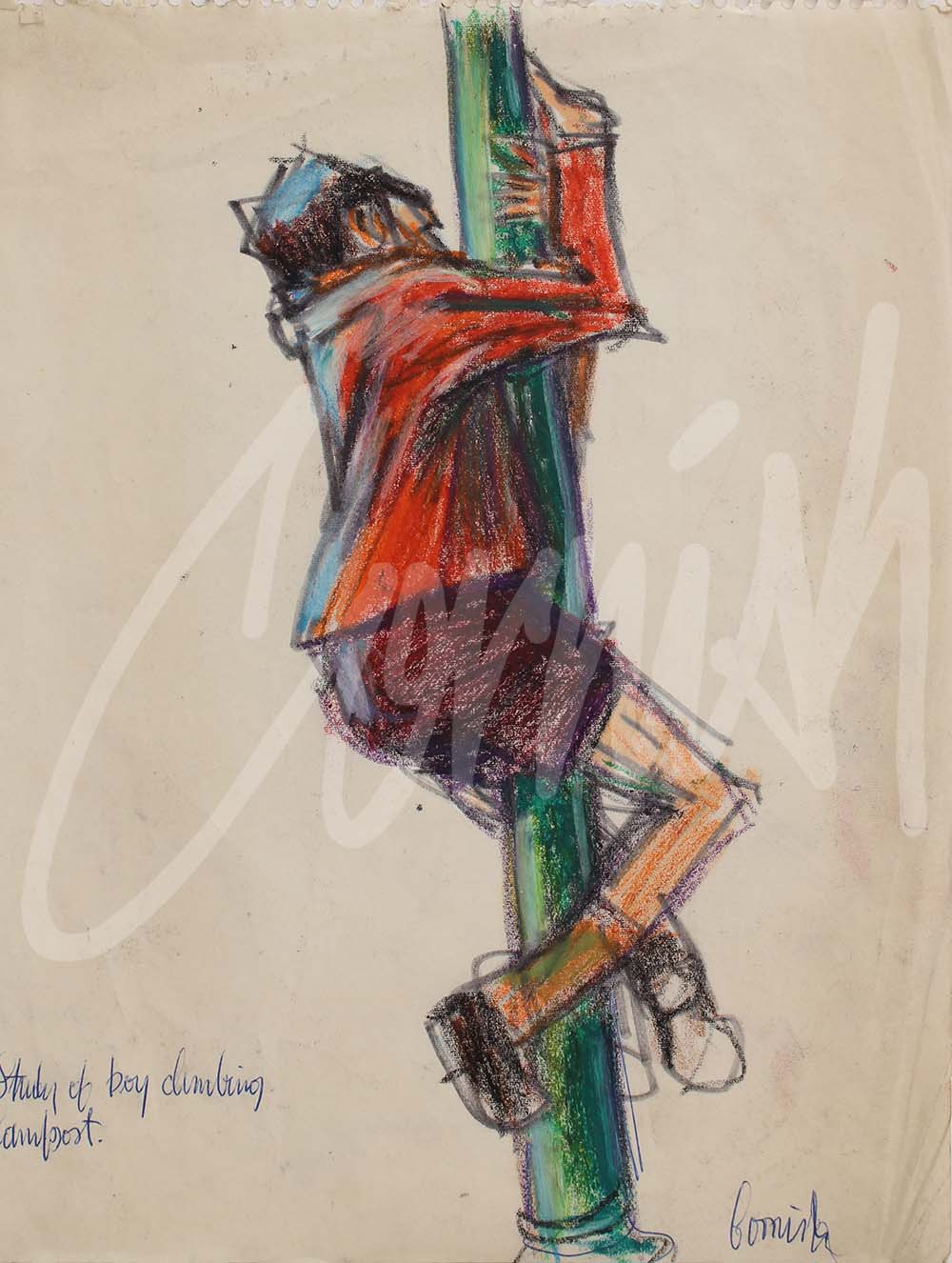

Growing up in the post war era will have indelible memories for this generation, with some common factors such as cold rooms, tin baths and outside toilets. Children ‘played out’ and residential streets were considered safe places to play unaccompanied. Children were encouraged to be adventurous. Some got dirty climbing trees and lamp posts and grazed knees were common as short trousers were worn. TV was rare and radio programmes were an important source of tales of adventure. Proper winters added to the excitement and adventure before ‘Health and Safety’ curtailed the opportunities to ‘slide on the ice,’ either on frozen ponds or on the school yard. Improvised pram wheels were also put to an alternative use to construct ‘bogies’ of various sizes which were also used in races.

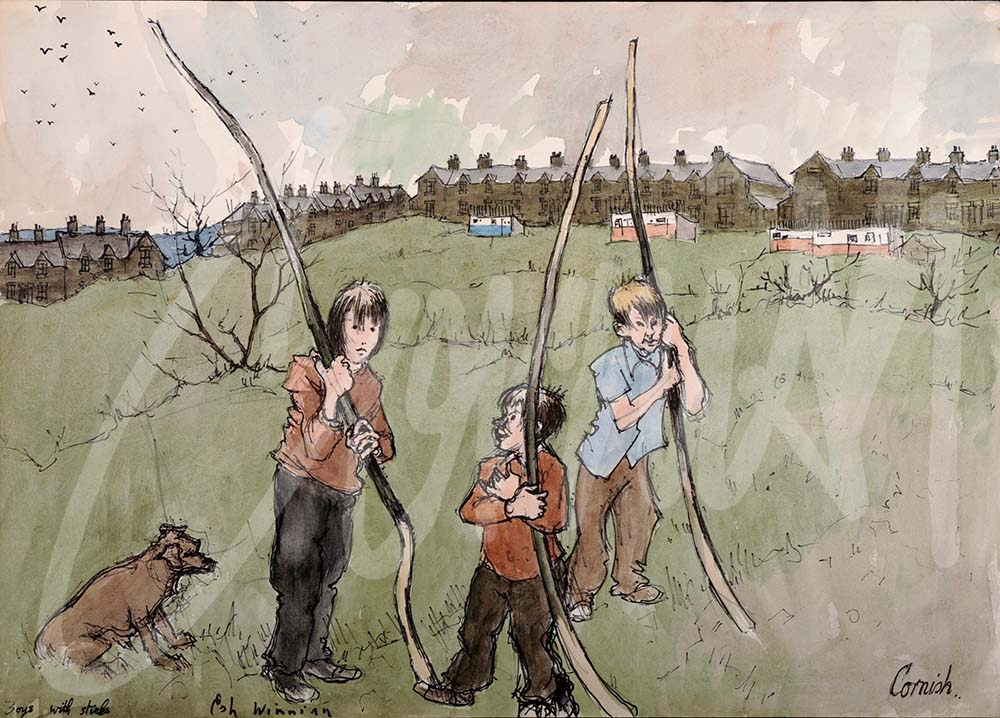

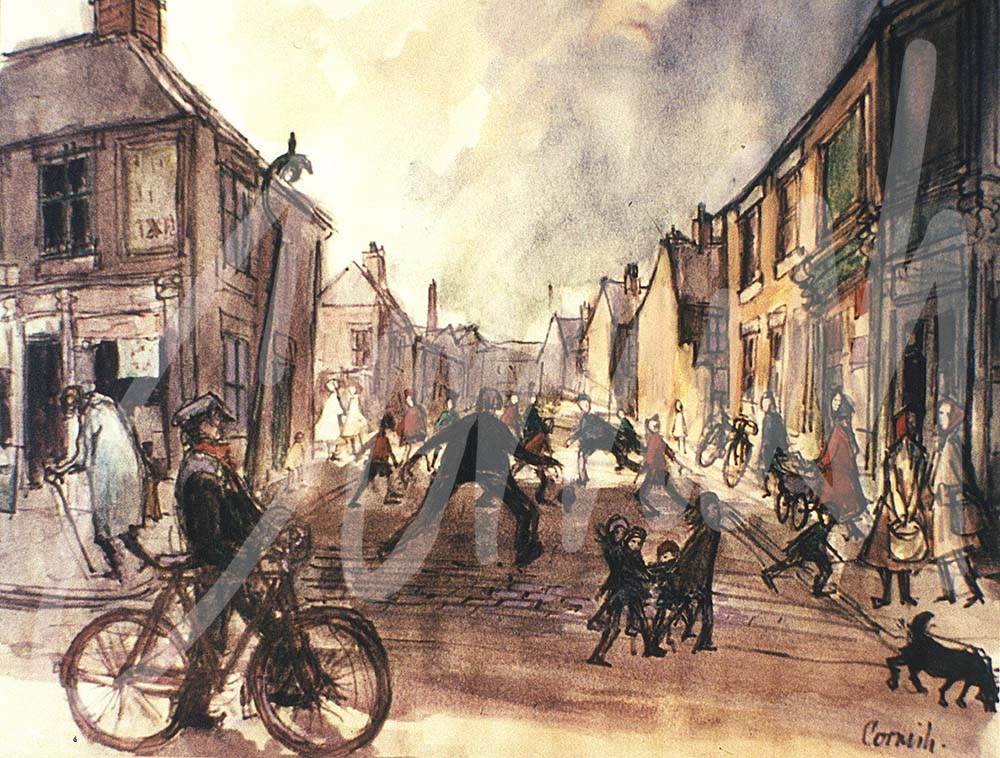

Cornish has chronicled a period of immense social change and, in the days before skate parks, mountain bikes, computers, theme parks and colour TV, he observed socially acceptable adventure which could be found in the immediate environment. His observations of children growing up in communities throughout the country show another slice of their life and times.

More Articles...

- Culture and Heritage: An artist’s tale.

- Viaducts

- Going to the Dogs

- Self Portraits

- Interesting Portraits

- Beamish’s 1950s terrace ready to open. Beamish’s 1950s terrace ready to open.

- The View from the Studio

- University Of Northumbria and The Permanent Collection

- Churches in and around Spennymoor

- Observations of people: