Latest News

Beamish’s 1950s terrace ready to open. Beamish’s 1950s terrace ready to open.

Great news!

Beamish, The Living Museum of the North will open its 1950s terrace with a week of celebrations this February Half Term, from Saturday 19th to 27th February 2022.

The official unveiling will take place on Friday 18th February at 11-30am and you will be able to join a global audience to watch the opening live at 11-30am on Beamish’s Facebook page.

https://www.facebook.com/BeamishLivingMuseum

Front Street terrace features John’s Café, Middleton’s Quality Fish and Chips, Elizabeth’s Hairdresser’s, and a recreation of the 1950s home of celebrated North East artist Norman Cornish.

Visitors will be able to enjoy an ice cream sundae while listening to the jukebox at John’s Café, a recreation of the popular café from Wingate, County Durham. They will be able to get a 1950s hairdo and pose for photos under the dryers at Elizabeth’s, which is in a recreation of an end-terrace shop from Bow Street in Middlesbrough. Fish and chips will be served at Middleton’s, which recreates a fish and chip shop from Middleton St George, near Darlington. Visitors can also try their hand at sketching in No. 2 Front Street, a recreation of Norman Cornish’s Spennymoor home and discover more about the Spennymoor Settlement.

All visitors will need to pre-book an entry timeslot to visit the museum. Please note the museum is not open on 18th February. Timeslots from 19th February to 27th March will be available to book on Beamish’s website now.

The terrace in The 1950s Town is part of the Remaking Beamish project, which also includes 1950s Spain’s Field Farm and an expansion of the Georgian landscape, including early industry and overnight accommodation.

Thanks to the money raised by National Lottery players, the Remaking Beamish project was awarded £10.9million by The National Lottery Heritage Fund in 2016.

For more information about visiting Beamish, see www.beamish.org.uk.

The View from the Studio

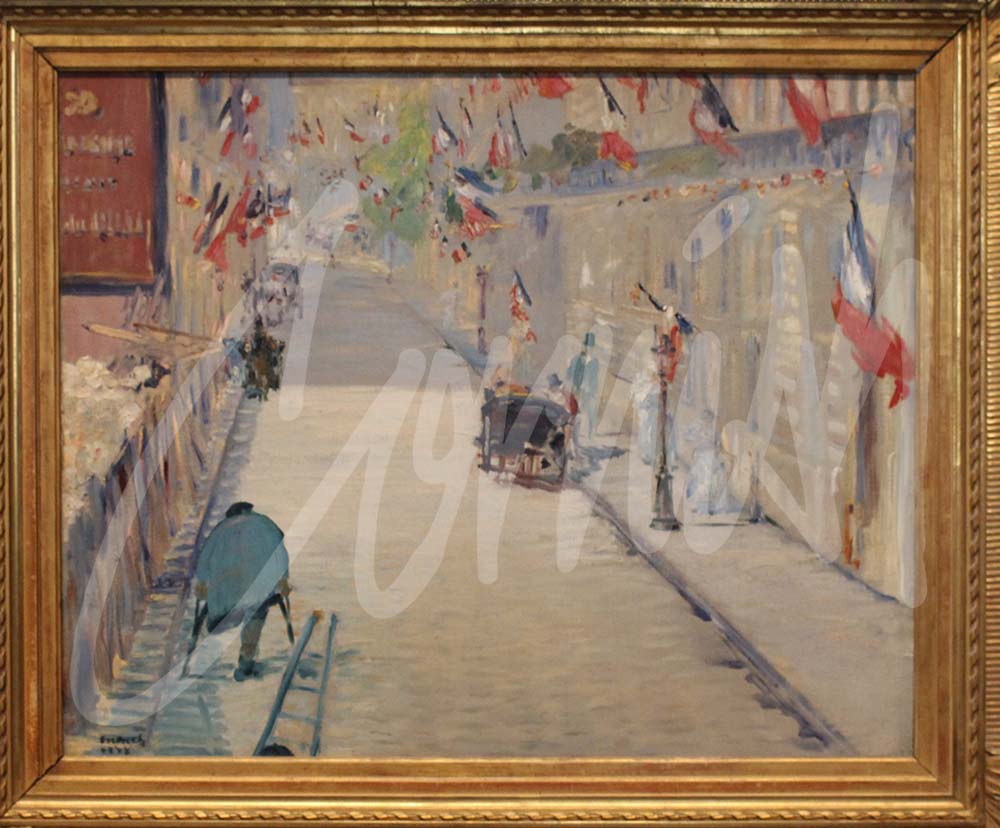

Artists usually consider the location and aspect of their studios to ideally capture natural light from north facing windows. LS Lowry (1887-1976) was an exception. He usually painted after 10pm in his ‘workroom’ until the early hours, with nothing other than an electric light.

Edouard Manet (1832-1883) provided a different approach with ‘Rue Mosnier with Flags.’ It was painted during a national holiday on June 30th 1878, which was a ‘Celebration of Peace.’ The painting depicts the scene from his second floor studio window during a holiday afternoon.

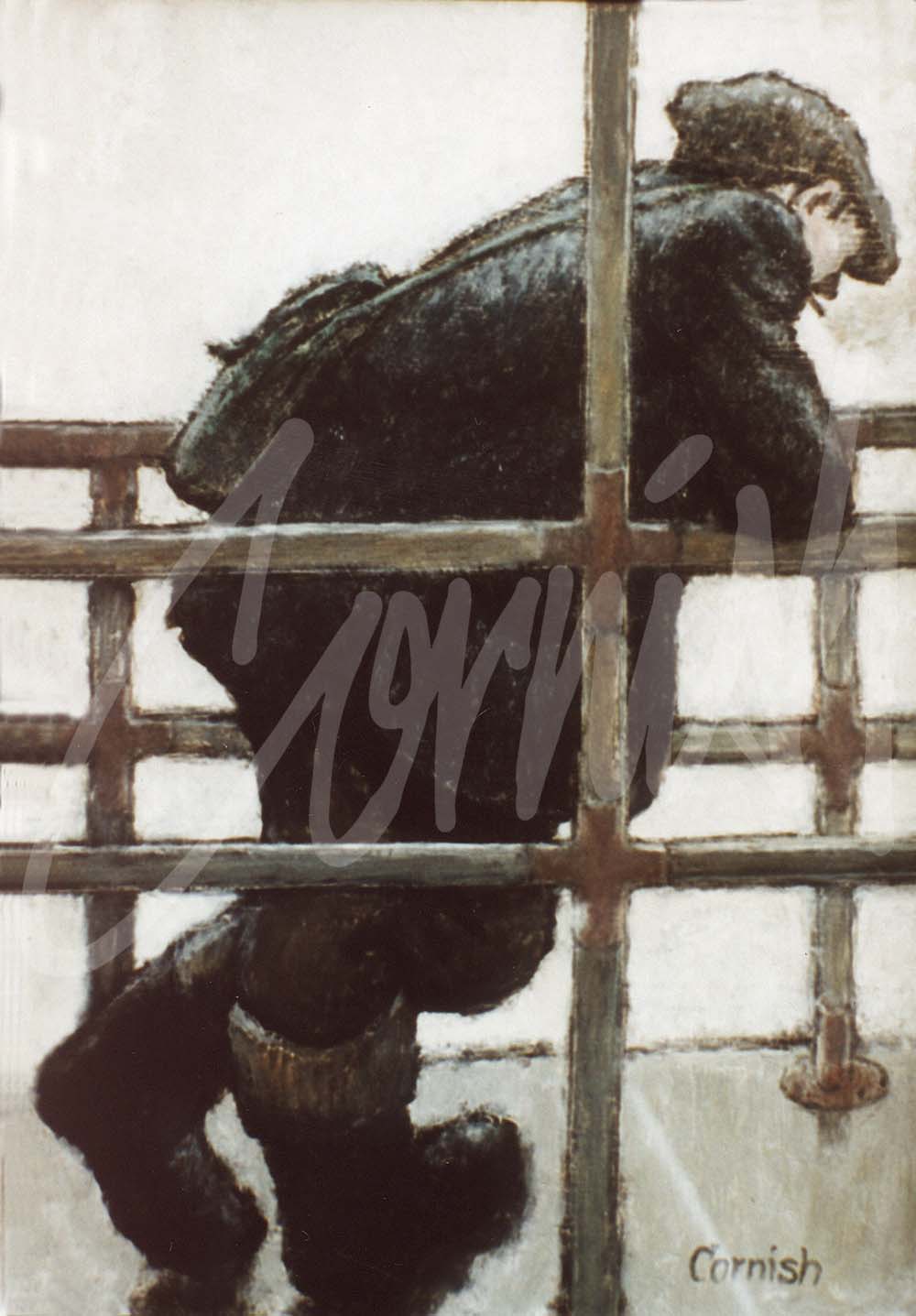

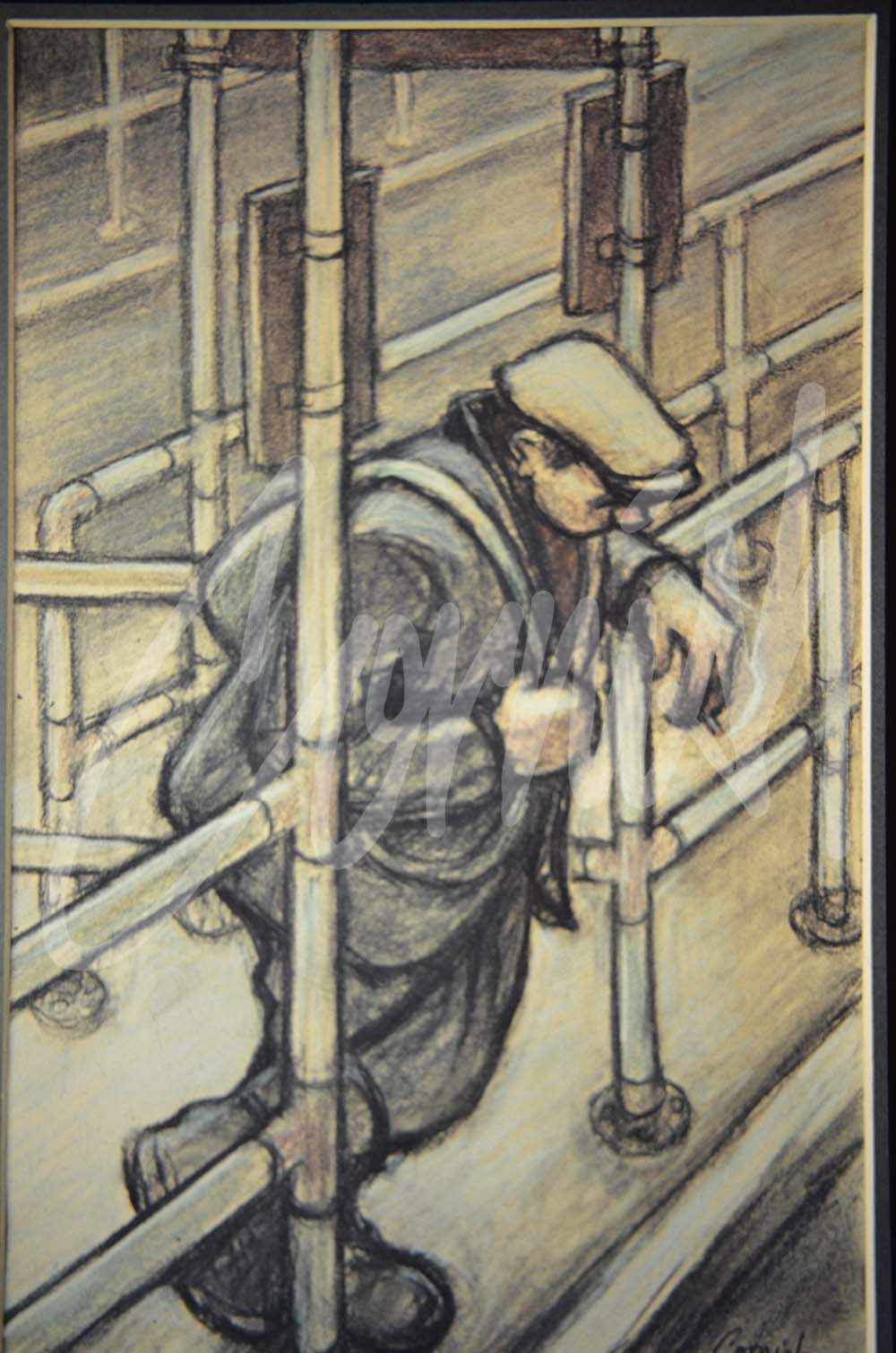

When the Cornish family moved to 67 Whitworth Terrace, Spennymoor, in 1967 Cornish acquired a suitable room as a studio that had originally functioned as a Methodist Minister’s office. The studio had two windows providing natural light with one of them facing north, thus avoiding direct sunlight. Downstairs, an old ‘front room’ became a second studio space which included a Morso frame cutter, storage for materials and two easels on which larger works could be placed.

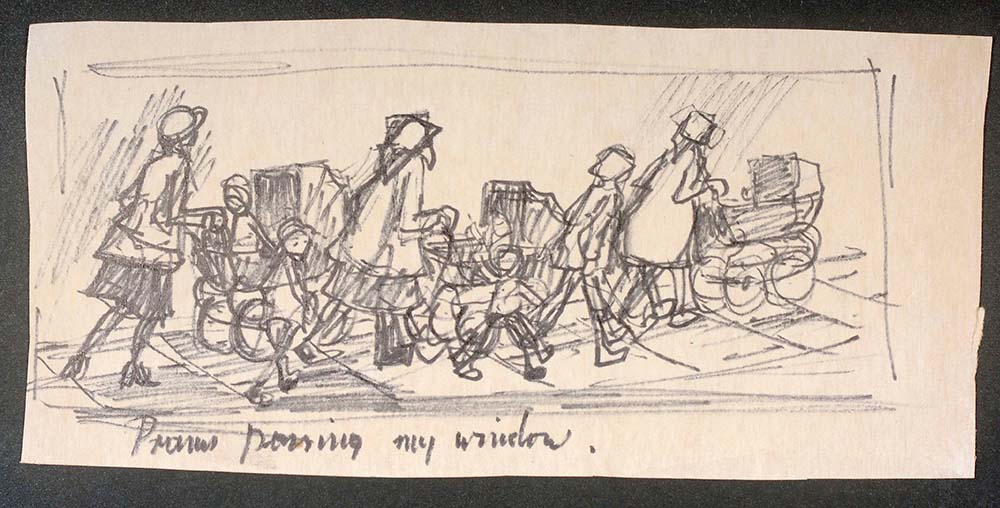

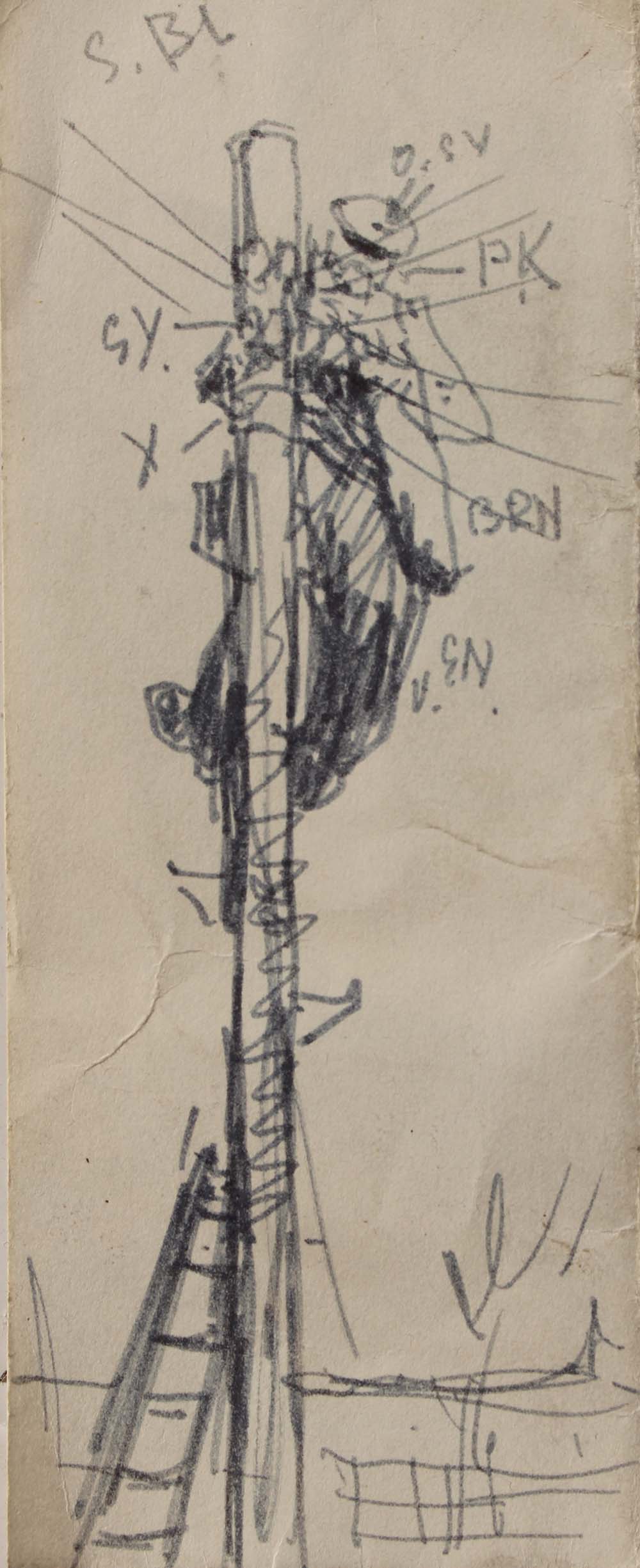

The front room also provided a window on the world passing by and another opportunity to observe his slice of social history in the area. People pushing prams became an irresistible subject for Cornish as an artist. The telephone engineer ‘up the pole’ was observed from the north facing window at the rear of the upstairs studio, and was clearly another activity of interest worthy of his attention.

Cornish was reluctant to own a telephone and it was only towards the end of his professional career that a telephone was installed in home. The reason was that he objected to being disturbed during periods of intense and focussed concentration. However, he always personally responded in depth to written enquiries and the recipients of letters have often retained this correspondence with pride, as a little piece of art history.

University Of Northumbria and The Permanent Collection

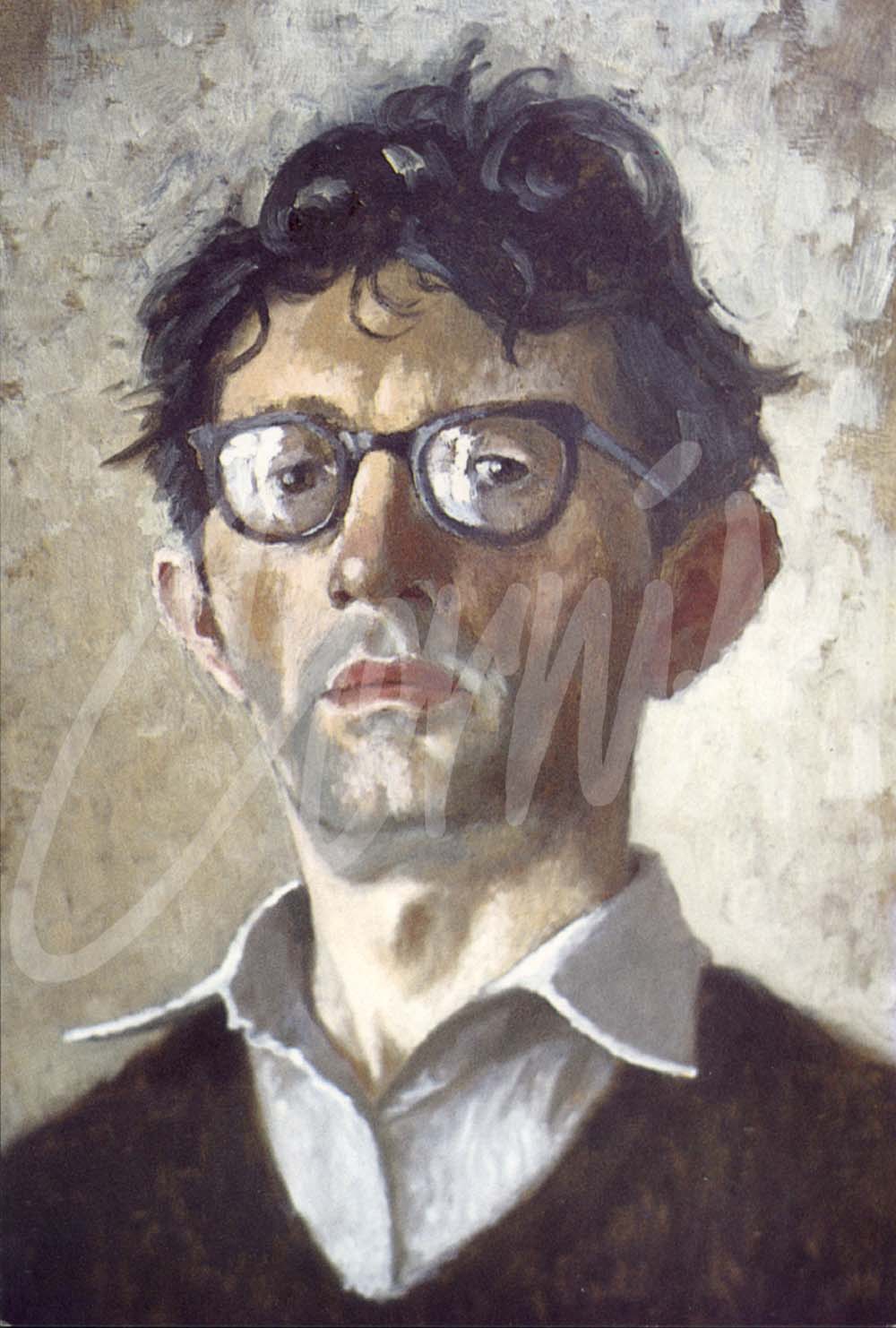

Norman Cornish first exhibited at Northumbria University over 30 years ago in 1989 and the relationship between Cornish’s family and the university continues to develop.

In December 1991 the first painting by Norman Cornish gifted to The Permanent Collection was donated by Bill Mallabar: Pit Road with Telegraph Poles

‘Gifted by William Mallabar in memory of his mother Margaret Mallabar’ accompanies the work when it is exhibited.

Bill Mallabar became a friend of Cornish and he printed and published Cornish’s autobiography ‘A Slice of Life’ in 1989.

This was the beginning of the Permanent Collection of works by Norman Cornish that have been donated by individuals and families for the ‘wider public benefit’. The paintings are occasionally loaned to other galleries in the region and beyond to support exhibitions. The paintings and drawings are correctly stored to meet exemplary standards in climate conditions and security.

The Permanent Collection also includes ten works bequeathed by the artist in 2002 as recognition of the enduring strength and significance of the relationship between Cornish and the university.

The university is also the home of the Cornish archive and currently the subject of a second PhD research project being undertaken by Lucas Ferguson-Sharpe into ‘The Techniques, Materials and Focus of Norman Cornish’s Practice’. The PhD research will be published later in 2022 via links from this page. The first PhD research was undertaken by Leanne Bunn and published in 2010, ‘Changing Landscapes: Norman Cornish and North East Regional Identity’ nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/3677/

The university supports other links with The Norman Cornish Estate Including:

- The programmes to develop the capacity to provide instrumental analysis of the materials used by Cornish during his career.

- The Coming Home exhibition at The Bob Abley Gallery in Spennymoor Town Hall

- The Norman Cornish Centenary Year during 2019

- Gallery North has replaced the original University Gallery on the same campus.

What should I do if I have something which may be of interest?

If you are interested in donating work by Noman Cornish to the Permanent Collection at Northumbria or placing works on long term loan, then please contact: Jean Brown This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A Jean E Brown

Associate Professor

Director of the University Art Collection

Preventive Conservation MA Programme Leader

Department of Arts

Faculty of Arts, Design & Social Sciences

Northumbria University

Newcastle upon Tyne

NE1 8ST

Churches in and around Spennymoor

The development of coal mining in County Durham started as early as medieval times and thereafter, according to geographical location as well as access, to export markets via rivers and ports. The development of new technology, particularly the emergence of steam railways, gave added impetus across the county although large tracts in the south east and far west had no coalmines.

Spennymoor itself had been built largely to support the Weardale Iron and Coal Company’s Tudhoe ironworks which continued coke- making until the 1950s. At its peak the Tudhoe Mill Ironworks were the largest in Europe. The first coal production began at Whitworth Colliery in 1840 and a number of other local mines also opened, with men recruited from those who had migrated from areas such as the Midlands, Wales and Lancashire.

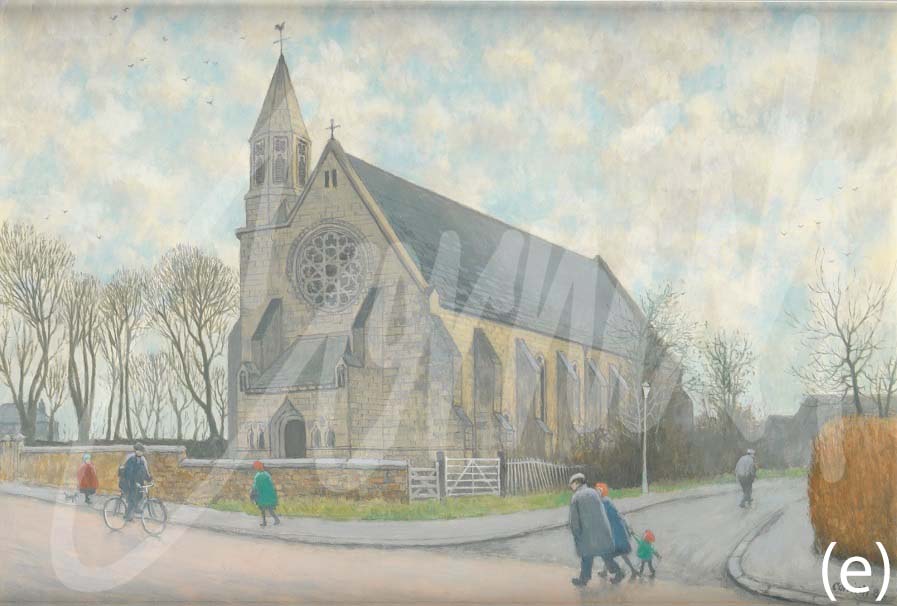

As the town grew in size Spennymoor officially came into existence in 1864, as a Local Board of Health with nine members was established to govern the rapidly expanding town. Other amenities and organisations followed such as schools for the children, shops, council offices and of course, churches and chapels. Two churches in particular have traditionally featured in drawings and paintings by Cornish. St Paul’s Church (a) (1856) will be well known to those who enjoy Cornish’s work. He drew and painted it from every conceivable angle and time of the day and in different weather and seasons. The example today of this favourite scene is actually being shown for the first time following a recent discovery. The Methodist Church (b) in Weardale Street near Dobby’s corner was demolished many years ago. The view down Salvin Street in Low Spennymoor is also making a first appearance and the Holy Innocents (C of E 1860) Church (c) continues to anchor the composition whichever view is taken. St Andrew’s Church(d) (1883), and RC Church of St Charles (e) (1870) are also both Grade 2 listed buildings.

However,one of the churches on the edge of Spennymoor, predates the whole emergence and development of the town during the mid-19th century. Whitworth Church,(f) adjacent to Whitworth Hall, the former home of Bobby Shafto who was the subject of the 19th century children’s song ‘Bonny Bobby Shafto.’ The church was mentioned in 1183 (Boldon Book) and rebuilt in 1808 with the addition of stained glass in every window.

Cornish never held any strong views about religion but he was well aware of the significance churches and religion played in the lives of many people in Spennymoor. With the passage of time many of the churches have survived and continue to flourish with strong local support, although many of the original Methodist chapels are no longer there. When the Cornish family re-located to Whitworth Terrace in 1967 it was to a former Methodist Minister’s Manse and the Minister’s office became an ideal space for Cornish to develop a studio as he progressed to being a professional artist for the next 45 years – a period of time much longer than his time underground as a miner, a fact often overlooked.

The Tudhoe and Spennymoor Local History Society always welcomes new members and thanks are due to Christine Ludbrook who created and administers their website which has provided much of the information for this feature today. http://www.durhamweb.org.uk/tslhs/index.html

Observations of people:

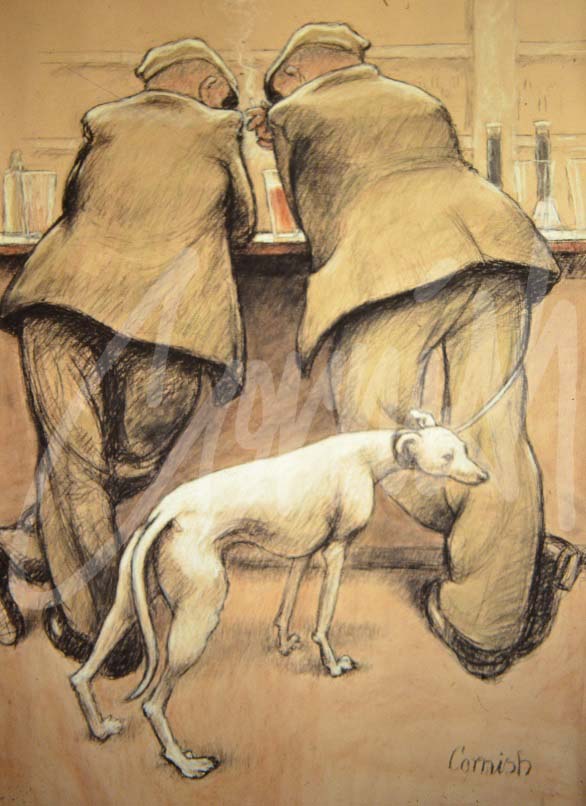

When Cornish lamented the gradual decline of the collieries, the pit road, pubs, chapels and many of the ordinary but fascinating people, we remain grateful that his ‘slice of life’ has provided a remarkable social record of those past times. His work is sometimes referred to as ‘social realism,’ and his attention to the humble and mundane activities of everyday life appears in so many of his street and bar scenes.

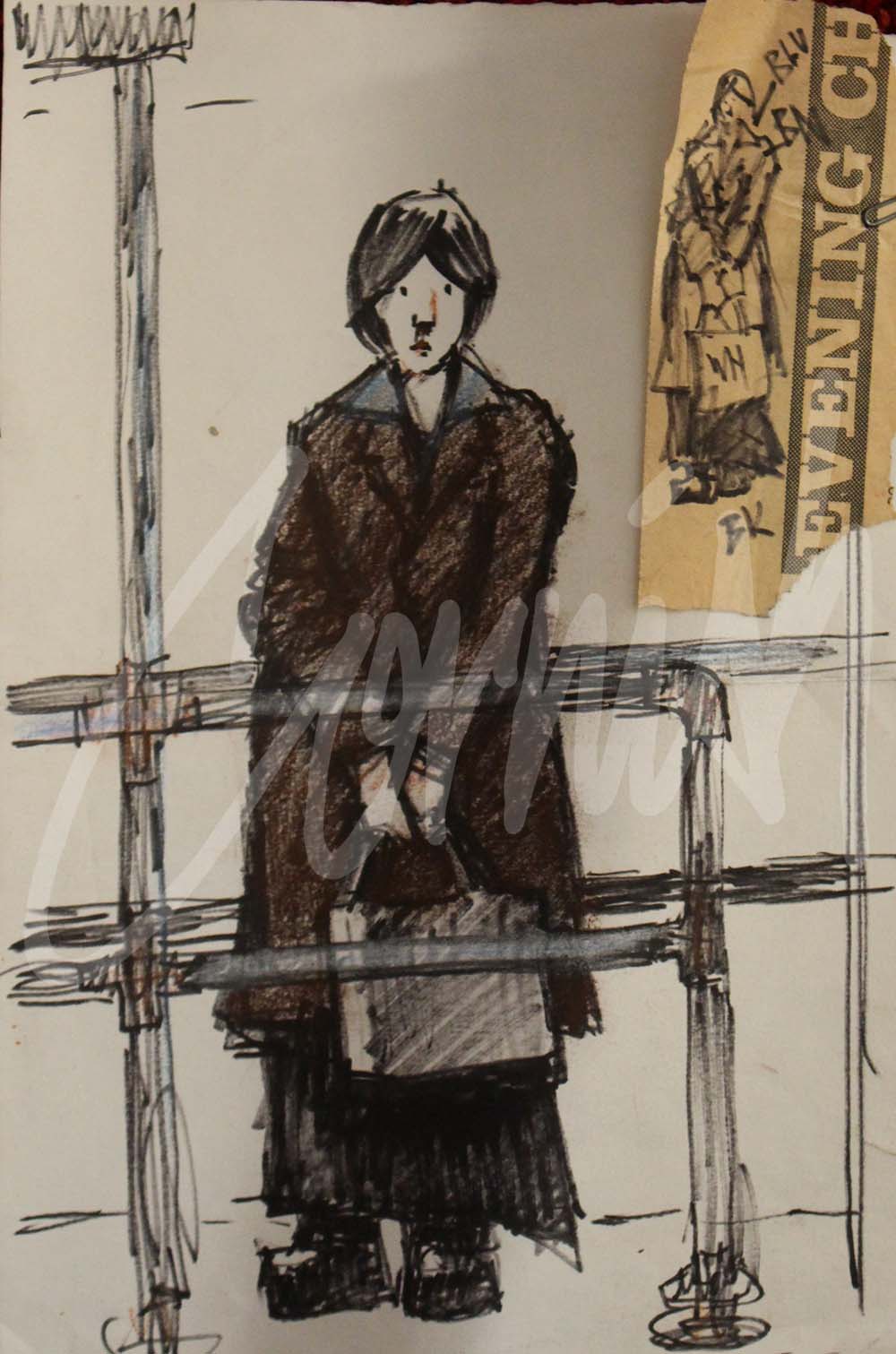

Whenever Cornish was out for a walk he always had his sketchbook and Flo-master pen in a specially crafted ‘poachers pocket’ that his wife Sarah had sewn into his coat. This meant that whenever something of interest captured his imagination he was quickly able to access materials to record a particular moment in time.

He walked to work every day to the Dean and Chapter Colliery at Ferryhill for almost 30 years: a distance of three miles in each direction. Occasionally his friend Jack Savage would give him a ‘run out’ in his car to some of the outlying villages in search of additional subject material. This was very fortunate for an artist who was unable to drive, and who also had no desire to learn to drive. In hindsight it was a blessing in disguise because he would have been unable to concentrate with so many interesting distractions appearing during a journey! Coincidentally, using public transport to visit places further afield also presented other opportunities and some examples are included here today.

Whenever he had to travel to Newcastle to visit his agent, Mick Marshall, at the Stone Gallery, Cornish would catch the OK bus which started its journey in Bishop Auckland and then on to Marlborough Crescent bus station in Newcastle, via Durham City. People at bus stops along the route became an obvious subject of interest and some readers may recognise the bus stands from North Road in Durham City. A scrap of paper on one occasion from the Evening Chronicle, a Newcastle newspaper, provided an opportunity to ‘snatch’ a preparatory sketch. Working men with ‘bait bags’ were ubiquitous and another source of interest. The view from a bus was also the opportunity for a different view point.

Cornish possessed a deep understanding of human behaviour and social interaction. He recorded local people going about their daily tasks, living real lives. Sometimes the drawings would become paintings and on other occasions would be included in the many street scenes synonymous with his work. Throughout his career he was conscious of his contribution to a sociological and historical record of people and places, in his ‘slice of life.