Latest News

Jackie Broomfield

One of the very interesting handwritten statements uncovered in Cornish’s studio during 2014 discloses another example of the principles which underpinned his overall approach to his observations and work.

’In our memories and also of course in history books most of the so called great events are usually well recorded, but sometimes the ordinary things that happen in our lives are not considered extraordinary enough for comment. Yet things are often very important nevertheless and sometimes give a reader a much better idea of the ‘times’ than the supposedly great events’.

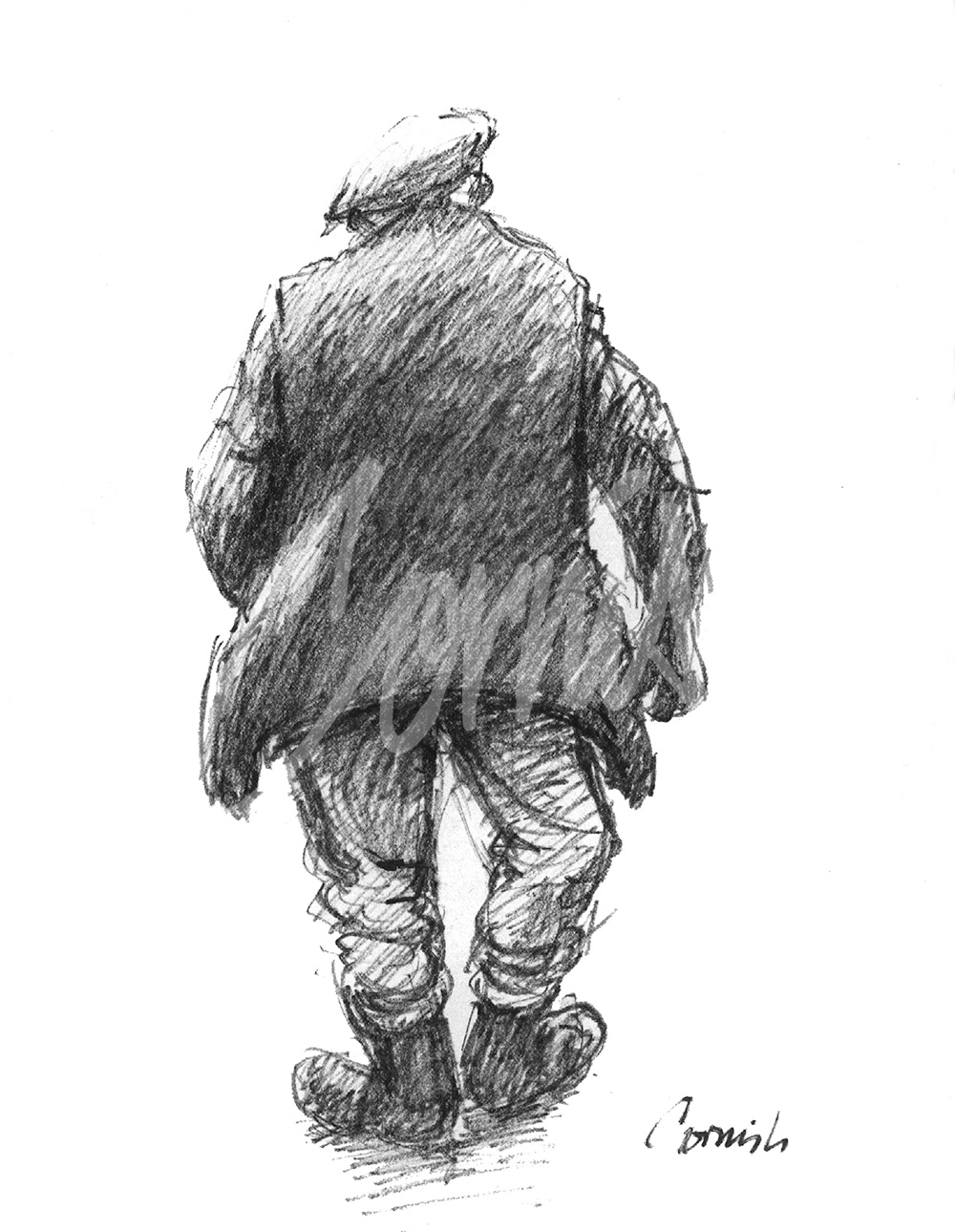

He produced hundreds of character studies, often in specific settings, at work, in pubs, on streets or people simply going about their daily lives. Moments quickly recorded that give us an aspect of heritage so familiar to many followers of Cornish’s work. His ability to work with speed and accuracy and to capture a moment in time was one of his strengths, using his Flo-master pen to great effect. A sketch book was a constant companion, kept in a ‘poacher’s pocket’ on the inside of a ‘donkey jacket’ along with his pen so that they were always immediately accessible.

Jackie Broomfield was a local character who was well known to Cornish. He became the subject on numerous drawings for many years and he was often seen on the streets of Spennymoor with his horse and cart, sometimes collecting scrap materials or doing ‘odd jobs.’ His horse, called ‘Dolly,’ provided a free source of ‘horse muck’ for those who were nimble enough to rush out and collect the manure for a garden or allotment.

Subjects such as these often invoke many memories, and Cornish’s drawings are imbued with a sense of recognition of people and places, that help us to develop feelings of nostalgia and regional identity. Jackie Broomfield with his ladder or horse and cart could of course be typical of scenes replicated in different parts of the country at different times, and some other artists have attempted to imitate the same subjects.

The difference is that Cornish’s work is based upon direct experience and personal knowledge that enables a realistic and authentic depiction of life and characters in times remembered.

Royal Jubilees

In his lifetime Cornish met various members of the Royal Family during their visits to Durham between 1963 and 2002.

Cornish first met Prince Phillip when he opened the new County Hall in 1963 and in 1989 the Duke and Duchess of York were visitors to County Hall as part of the Durham County Council centenary celebrations. Cornish was commissioned to produce a smaller version of the mural to be presented to the royal couple and the painting is most likely part of the Royal Collection.

In 1977 the Queen’s Silver Jubilee was celebrated on July 14th during a programme of extensive visits throughout the UK. Ten million people took part in street parties with the traditional bunting and flags.

In 2002 HRH Prince Phillip was to return to Durham along with HM Queen Elizabeth during the Queen’s Golden Jubilee celebrations. Durham Castle was the venue for lunch accompanied by the Chancellor of Durham University Sir Peter Ustinov and Cornish was introduced to the Queen who asked ‘what do you do?’ to which he replied, ‘I’m an artist and I paint people.’

Royal Jubilees are an occasion to celebrate the life and reign of a Monarch and they are significant events which are celebrated around the world. The Platinum Jubilee is officially on June 2nd and celebrations have been ongoing for some time and they may be a new experience for younger generations.

It was hardly surprising that the celebrations in 1977, which were within a short distance from the family home in Whitworth Terrace, were visited by Cornish to record another and very different piece of social history. Two photographs were taken of local street parties and two drawings in one of his sketchbooks quickly recorded the atmosphere and community spirit in Edward Street. This local street was one of his favourite subjects and always offered new and interesting situations whatever the time of day or season of the year.

The occasion was 45 years ago and some local residents may have fond memories from that time. The images are from the extensive archive of photographs taken by Cornish to assist the development of his work in his studio and the rare drawings are from the collection in his sketchbooks. What is not known is whether the images were later used in a painting?

Behind the Bar

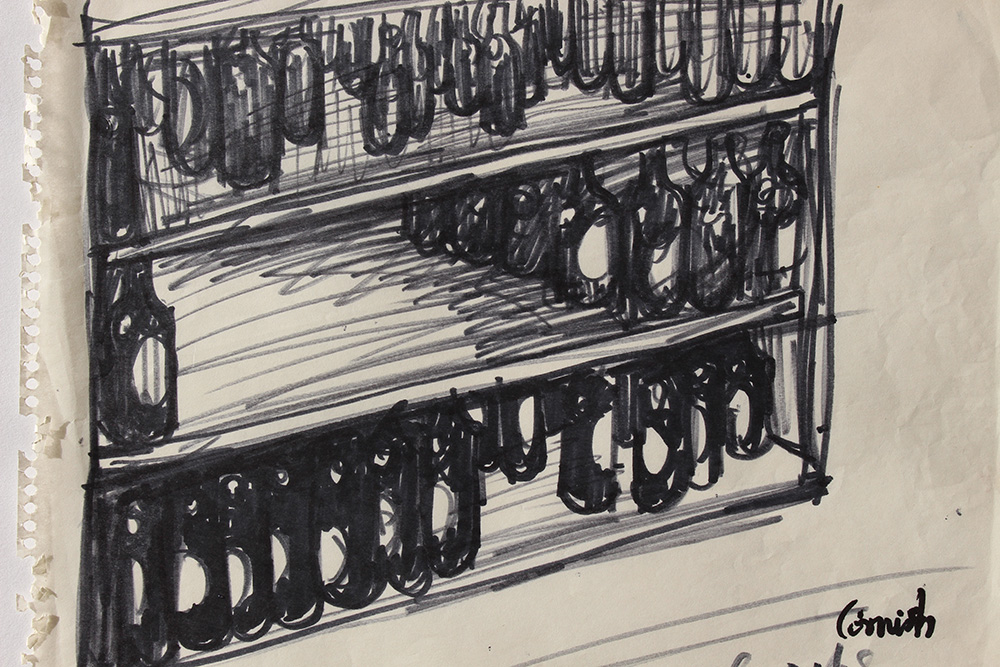

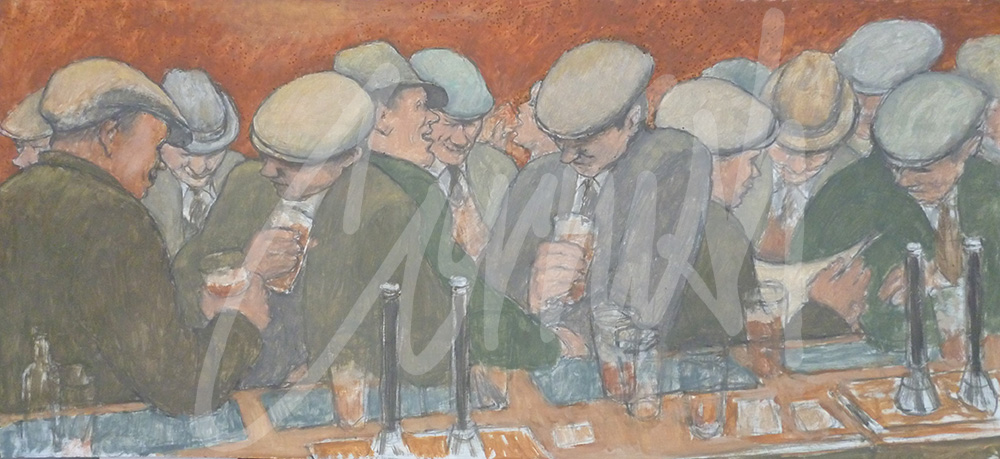

Popular terms such as landscape, seascape, townscape and cityscape may be well known to those interested in the visual arts, including photography. Many years ago Cornish introduced a new term when his observations in pubs took him ‘behind the bar’ - a bottlescape.

At one time there were over 35 pubs in Spennymoor and they became a favourite source of subject material for the drawings that became the foundation for his iconic ‘bar scenes.’ For over 30 years a miner by day, but with the eye of an artist at work observing ‘the things around him’ and his drawings and paintings eventually became a wonderful social record of his life and times in his era from the 1930s until the early 70s.

One of his favourite ‘locals’ was nearest to the end of Bishops Close Street but he also frequented other pubs in Spennymoor such as The Wheatsheaf, The Lord Raglan, The Pit Laddie and later in his career The Hillingdon which was close to Whitworth Terrace and the family home from 1967. In his own words:

“I made drawings of pub interiors in days past because I was fascinated by the men standing at the bar drinking and talking, or playing dominoes. I also realised that life would change in some ways. Today people still drink in pubs but the atmosphere has changed.”

As a professional artist Cornish was very thorough in his research: chairs, tables, posters, beer pumps and pint glasses all received his close observation and it is hardly surprising that his preparatory drawings took him ‘behind the bar.’ He was equally well known to barmaids and landlords who, like the men drinking and playing dominoes, would accept him as ‘one of the lads’ rather than as an artist at work.

“The people make the shapes I am just the medium.’

The actions of the barmaid ‘pulling a pint’ were a huge attraction for Cornish as a subject worthy of drawing. From different angles and perspectives, with her feet firmly planted, several pints balanced on a tray as each glass was filled in sequence to ensure a proper measure, and the angular arm pulling the beer pumps so that the whole process was completed to perfection. An obvious observation for an artist of his calibre.

A portrait of the barmaid at the Bridge Inn appeared on the BBC Antiques Roadshow earlier this year and the pub eventually adopted a new name, the Brewer’s Arms. Outside on the pavement, within site of the former end of Bishops Close Street is a board which is part of the Norman Cornish Trail and illustrating some of those iconic ‘bar scenes’.

The Creative Process Part 4 The Crowded Bar

One of the popular questions at the end of public lectures about Cornish’s life and work has always been about the process undertaken by Cornish to create his paintings and in particular his larger works on canvas. A popular misconception is that a completed picture is produced as a single exercise from beginning to end. The creative process is actually a very engrossing and mentally taxing exercise for the artist, demanding maximum concentration, and can often take days, weeks or even years to complete as the artist revisits the work several times. Cornish worked in silence unlike Lowry who listened to classical music as he worked late into the evening. Both artists delayed the acquisition of telephones until much later in their lives to avoid unnecessary distractions.

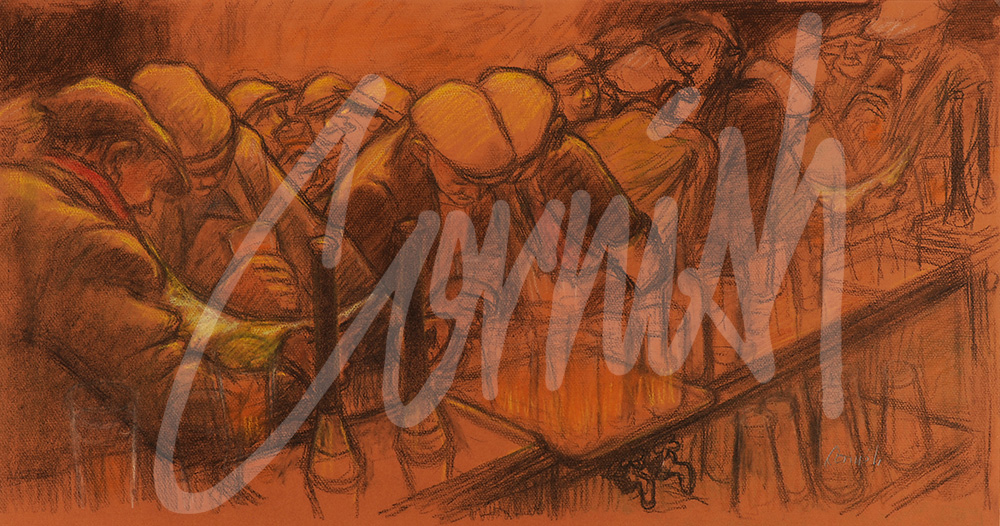

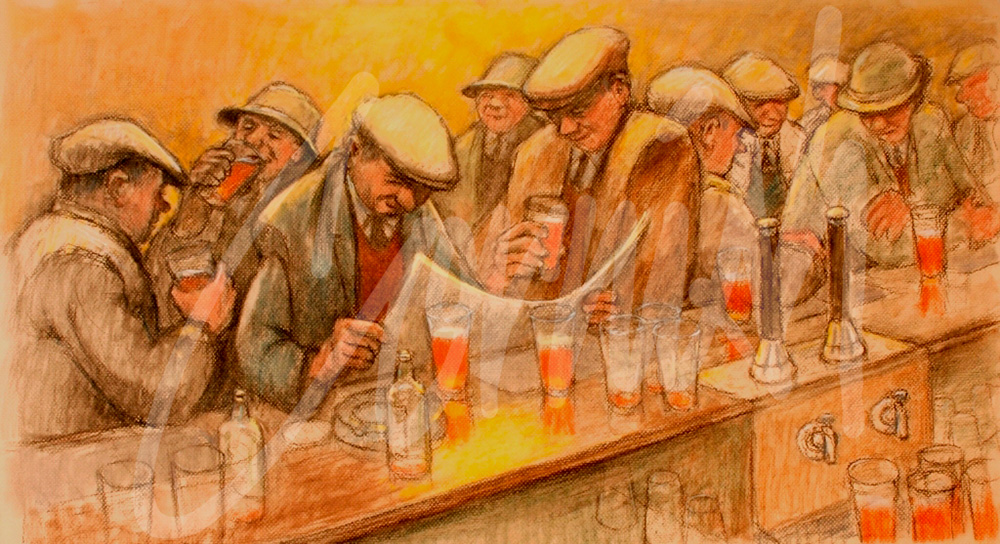

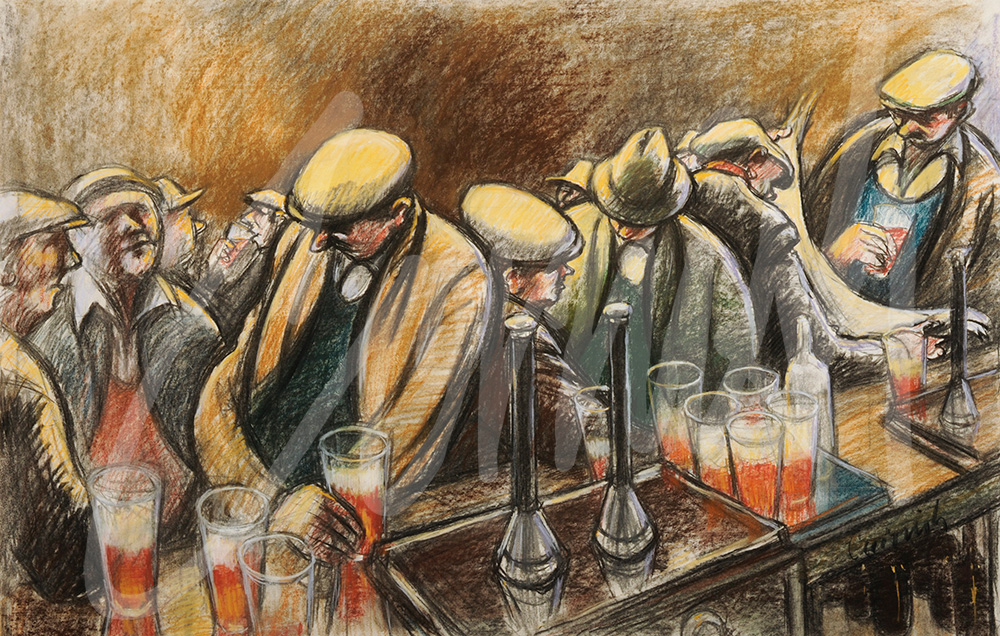

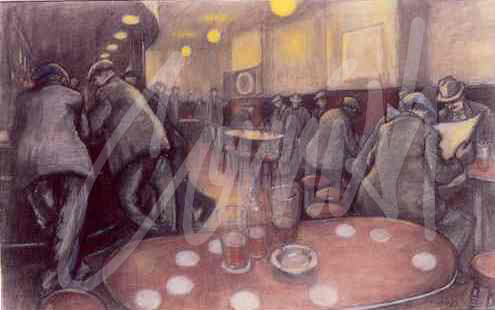

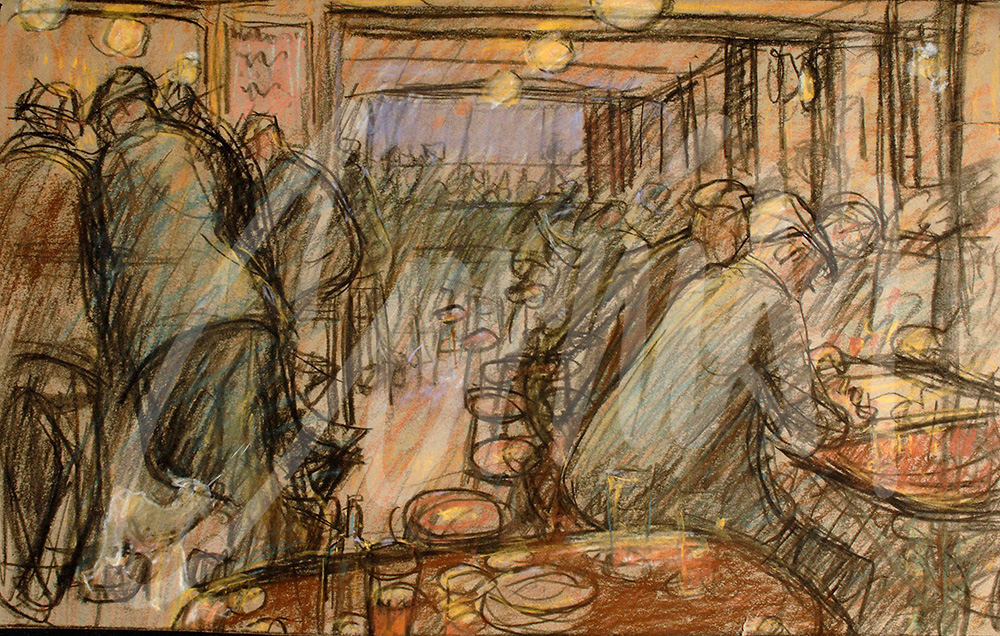

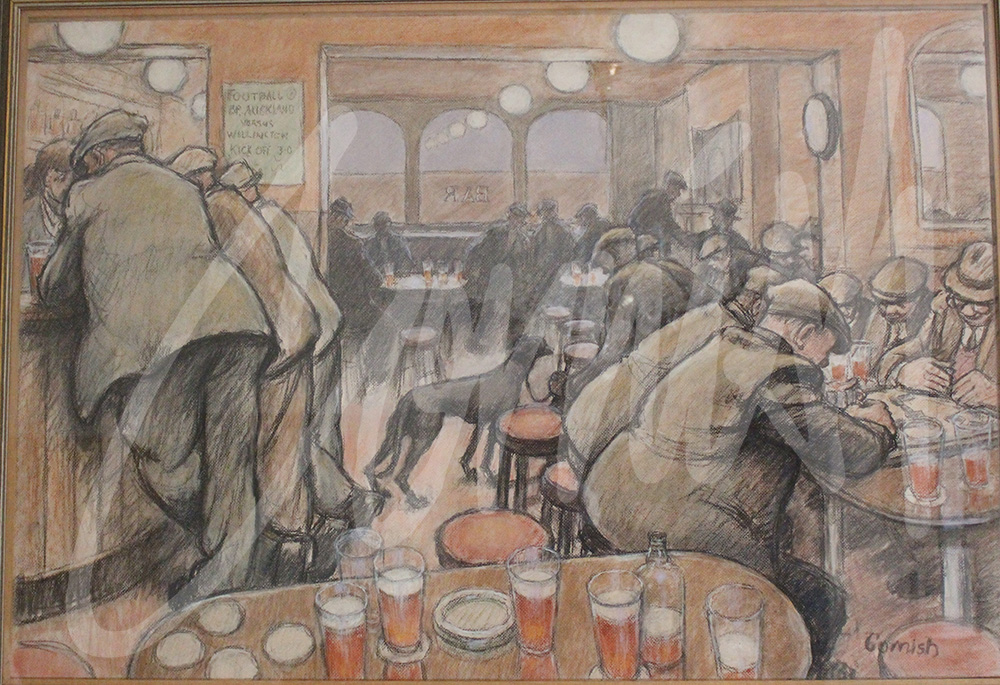

The pictures accompanying this feature provide a wonderful, example of the evolving steps to achieve satisfaction with the outcome of a subject re-visited on several occasions over the years. Coincidentally this approach was taken by both Cornish and Lowry with subjects repeated with minor adjustments in the search for perfection.

The Busy Bar provides a classic example and much thought would go into the underlying geometry of the images and their layout, which Cornish considered to be an abstract form in itself, giving rhythm and structure to the picture. Note for instance the development of the composition from the unusual angle viewed from behind the bar directly opposite the drinkers and then the angle becomes a diagonal. The diagonal undergoes some subtle changes including a higher viewpoint to reveal other men seated and then a detailed close up of the man with the newspaper.

Finally, the rationale behind the classic composition with underlying principles was discovered written by Cornish on a scrap of paper in his studio. ‘Human drama based on gesture and attitude, monochromatic with the accent on atmosphere which contrasts the earthy humanism and mysterious glitter of the beer and the glasses.’ This just about sums it up !

In 1989 the Busy Bar was purchased by Scottish and Newcastle Breweries for their boardroom. In 2007 the painting was donated to the Permanent Collection at Northumbria University for the ‘public benefit’ at future exhibitions.

Next week: The creative process Part 4.

The Creative Process Part 3 The Busy Bar

One of the popular questions at the end of public lectures about Cornish’s life and work has always been about the process undertaken by Cornish to create his paintings and in particular his larger works on canvas. A popular misconception is that a completed picture is produced as a single exercise from beginning to end. The creative process is actually a very engrossing and mentally taxing exercise for the artist, demanding maximum concentration, and can often take days, weeks or even years to complete as the artist revisits the work several times. Cornish worked in silence unlike Lowry who listened to classical music as he worked late into the evening. Both artists delayed the acquisition of telephones until much later in their lives to avoid unnecessary distractions.

The pictures accompanying this feature provide a wonderful, example of the evolving steps to achieve satisfaction with the outcome of a subject re-visited on several occasions over the years. Coincidentally this approach was taken by both Cornish and Lowry with subjects repeated with minor adjustments in the search for perfection.

The Busy Bar provides a classic example and much thought would go into the underlying geometry of the images and their layout, which Cornish considered to be an abstract form in itself, giving rhythm and structure to the picture. Note for instance the development of the composition from the unusual angle viewed from behind the bar directly opposite the drinkers and then the angle becomes a diagonal. The diagonal undergoes some subtle changes including a higher viewpoint to reveal other men seated and then a detailed close up of the man with the newspaper.

Finally, the rationale behind the classic composition with underlying principles was discovered written by Cornish on a scrap of paper in his studio. ‘Human drama based on gesture and attitude, monochromatic with the accent on atmosphere which contrasts the earthy humanism and mysterious glitter of the beer and the glasses.’ This just about sums it up !

In 1989 the Busy Bar was purchased by Scottish and Newcastle Breweries for their boardroom. In 2007 the painting was donated to the Permanent Collection at Northumbria University for the ‘public benefit’ at future exhibitions.

Next week: The creative process Part 4.