Latest News

A Remarkable Story

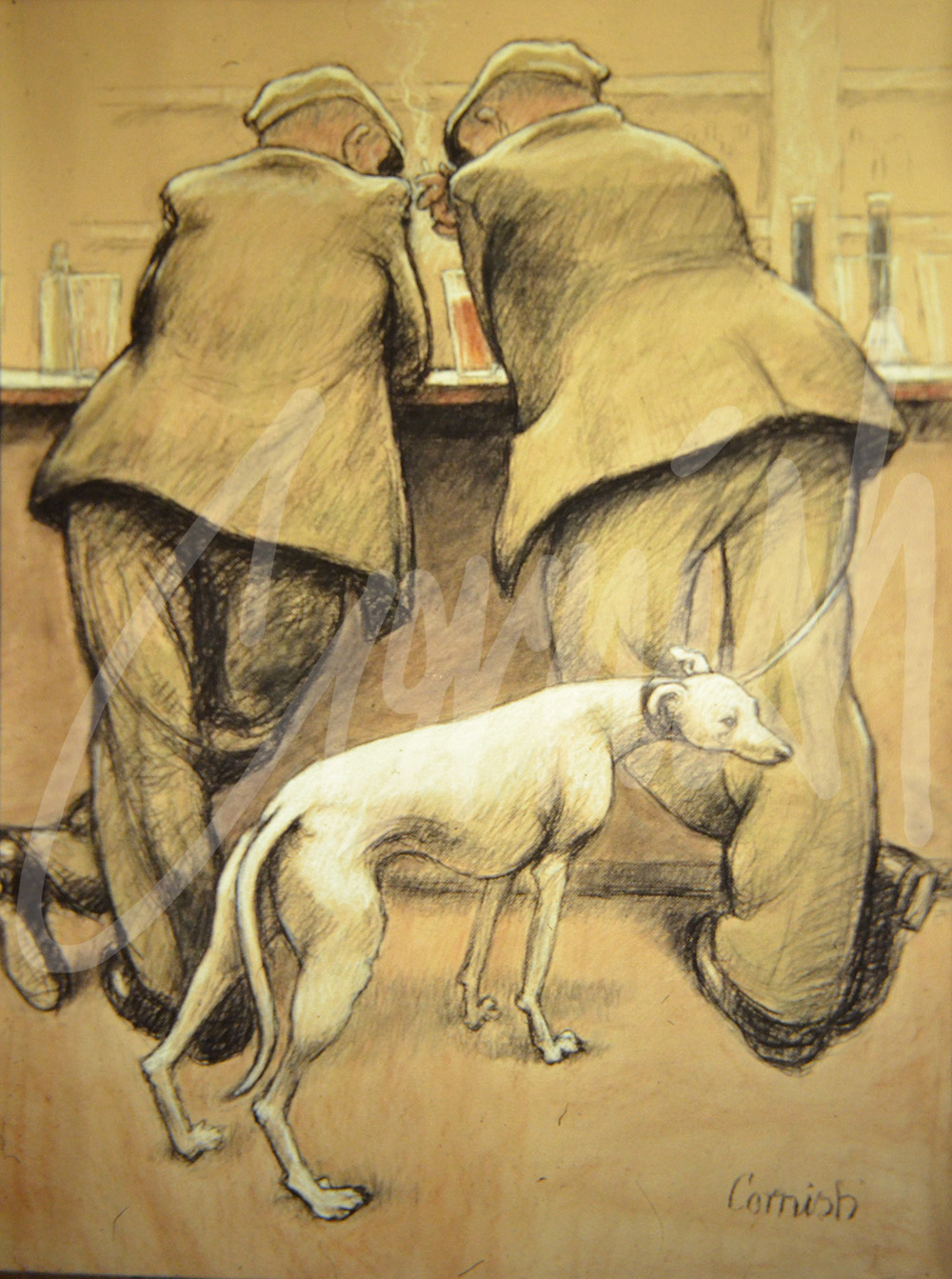

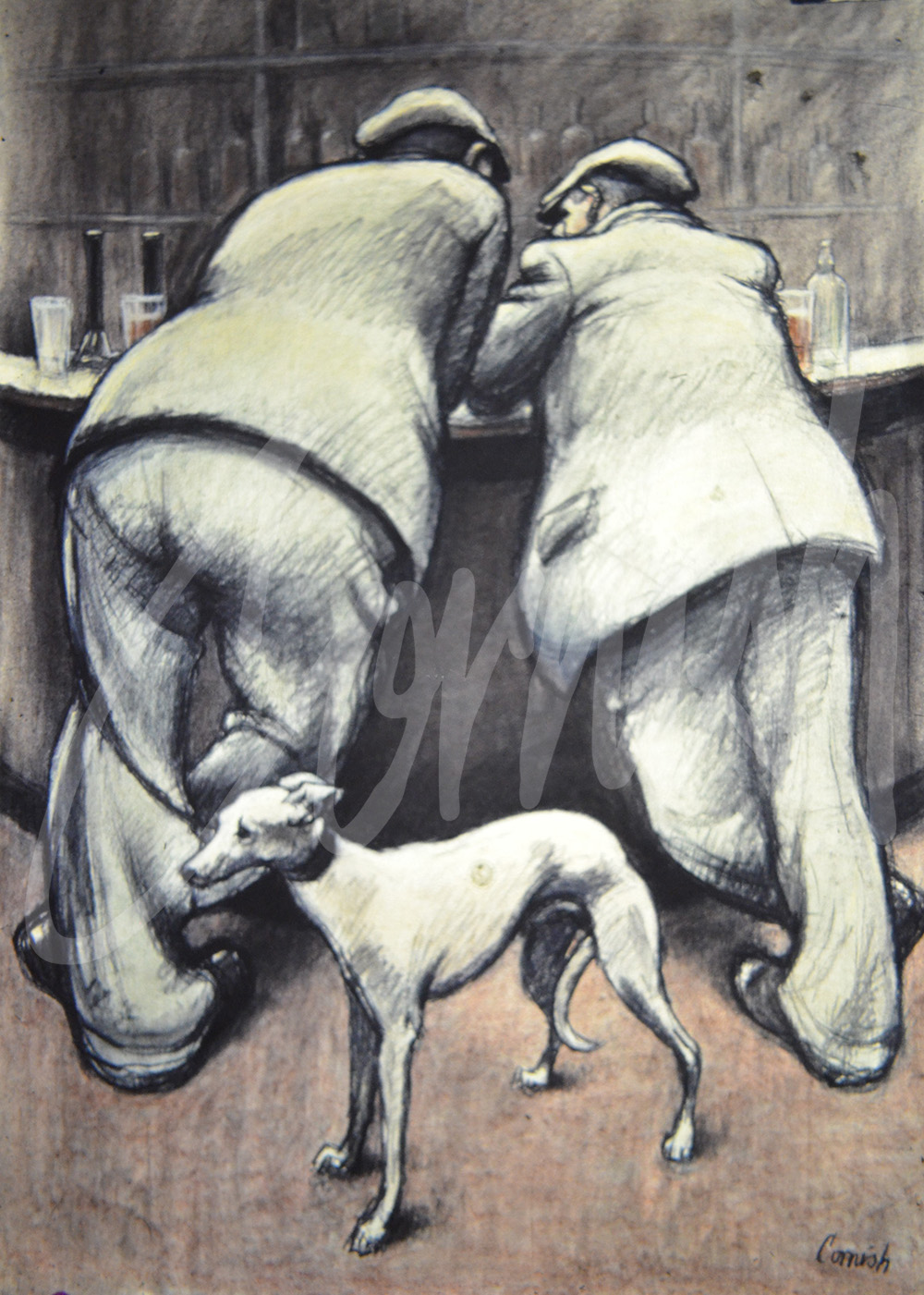

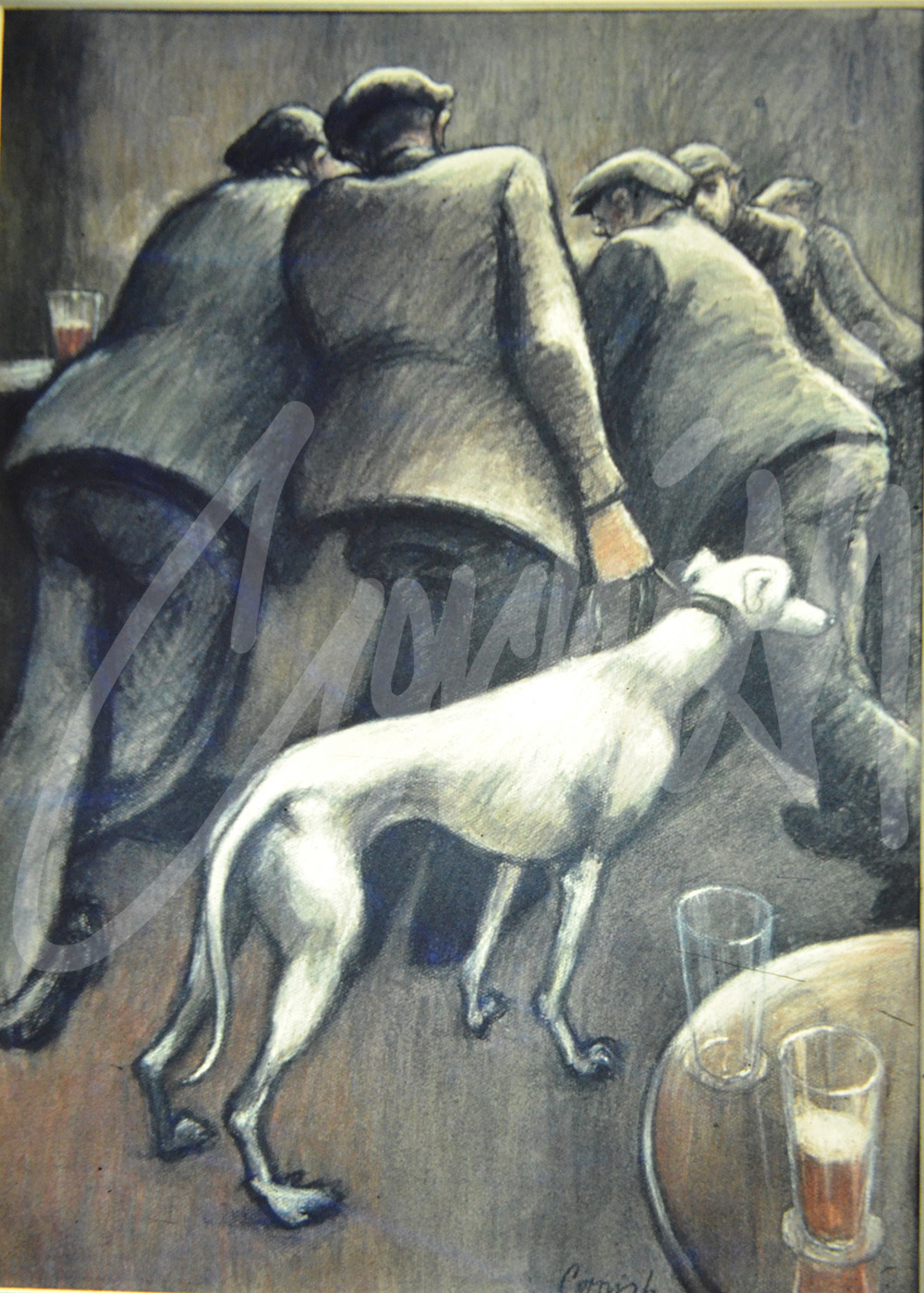

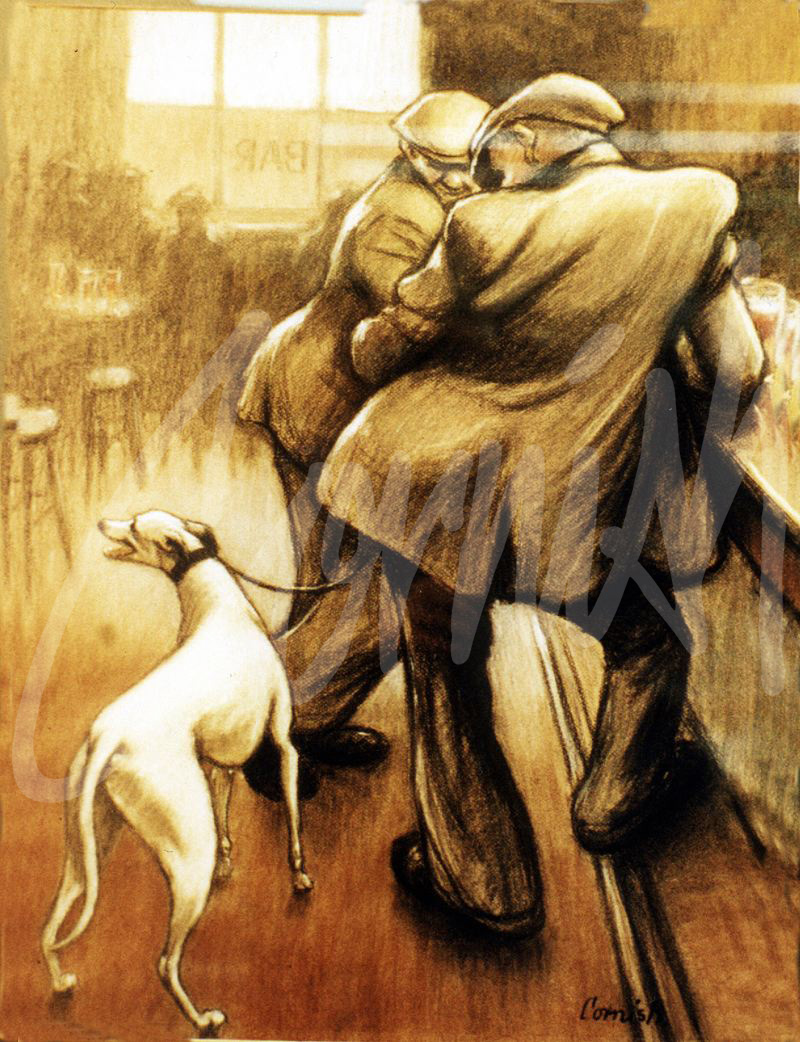

The picture featured today has always been known as ‘Dog Talk,’ and some versions are listed as ‘Two men at the bar with dog’. At the ‘Shapes of Cornish’ exhibition in 2016 at the Greenfield Gallery in Newton Aycliffe, a silence descended over the invited guests for the ‘private view’ as they prepared to hear the opening remarks from a local dignitary…. a former resident of Spennymoor and friend of Cornish. He caught sight of that particular picture in the corner of the gallery and immediately abandoned his prepared comments as he exclaimed to the astonishment of the guests, ”I know those two, Joe Hughes and Tosser Angus!” The local dignitary then proceeded with what can best be described as a remarkable story

As young teenagers, they both worked underground at Whitworth Colliery in Spennymoor and life was hard. The lads were also members of the Territorial Army and one of the attractions of being in the TA was the annual camp at the end of August that in 1939 was held at Scarborough. With WW2 being imminent both men were immediately conscripted as full- time soldiers into the Durham Light Infantry, rather than the reserved occupations such as coal mining at Whitworth Colliery. The men saw action in France and Belgium before being evacuated from Dunkirk, and were amongst the last of the men to leave the beaches in ‘C’ Company 6th Battalion DLI. They subsequently saw action throughout WW2 at Mareth (hand to hand fighting) Tunisia, and Primasole Bridge during the allied invasion of Sicily in 1943.

Fortunately, both men survived without a scratch and returned home to resume their lives working underground at Whitworth Colliery.

The dog at their side was no ordinary dog….His name was Piper- following the tradition of dogs being named after musical instruments in the DLI. Piper was acquired by Joe as a pup to ‘settle a debt’ and eventually became one of the top racing greyhounds in England, travelling countrywide in order to compete. From the cash ‘winnings,’ gained by Piper, Joe Hughes and his wife were able to indulge themselves in a holiday to Rome.

The story and the images are all featured in ‘Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks’ and they provide another example of Cornish’s creative process of fine tuning the composition, but also the characters being worked into the much larger bar scenes that are often referred to as ‘conversation pieces,’ where the subjects appear to interact with each other.

A Famous Fairground

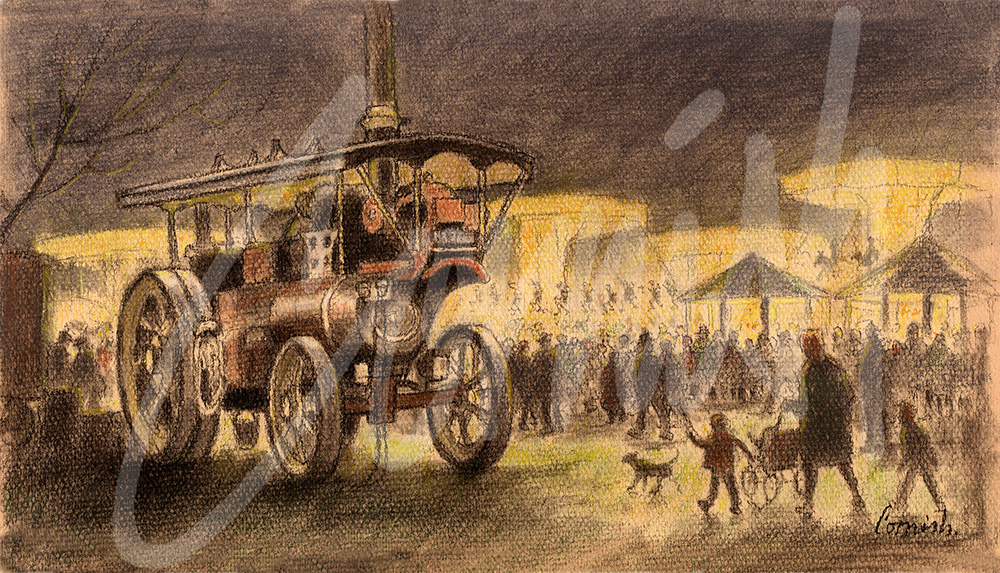

Many of the paintings and drawings by Norman Cornish can be identified in terms of time and place along with an interpretation or narrative. This has never been a simple challenge when the subject is unusual but, nevertheless, acquiring the story behind the picture has always been an intriguing task. A very good example may be found on page 129 in ‘The Quintessential Cornish’ - Traction Engine - Pastel, Private Collection. A slightly different version was uncovered in the archive of images of early work. One of the most famous fairgrounds in the country was resident in Spennymoor and the search for an answer could lead only to one man.

John Culine MBE was born in 1947 into a fairground family, in a caravan in Jubilee Park in Spennymoor. He attended King Street School and until recently he was president of the Showman’s Guild, the national body representing the fairground industry. He was a Town Councillor for 18 years and Mayor in 2004- 05 as well as being an MBE for services to ‘showmen and the community.’ Family members range from Alice Culine who crossed Bridlington harbour on a tightrope to Cliff Culine who appeared with William Cody (Buffalo Bill) on Durham Sands in 1894 as a knife and tomahawk thrower when Cody brought his ‘Wild West’ show to England.

John Culine and Norman Cornish were well known to each other and on one occasion Cornish was asked to paint some cartoon figures onto one of the fairground rides. The task was completed reluctantly and details remain shrouded in secrecy! However, two pictures did eventually emerge during the 1950s when the King Carnival Traction Engine was an obvious attraction during the two weeks when the fairground was in the Jubilee Park for the annual ‘Spenny Gala’ celebrations. One version records the atmosphere late in the evening and a similar version during daytime captures the ‘fun of the fair’ with waltzers, the chairoplanes, rodeo, Noah’s Ark Speedway, The Cake Walk, Shuggy Boats, Dodgems and test your strength.

A relatively unknown fact about the Showmen’s Guild was that it was a philanthropic organisation and during the world wars their lorries were donated to the government to help the war effort along with the purchase of 12 ambulances in the first World War and the cost of a Spitfire called ‘Fun of the Fair’ was donated to the Polish squadron during World War 2.

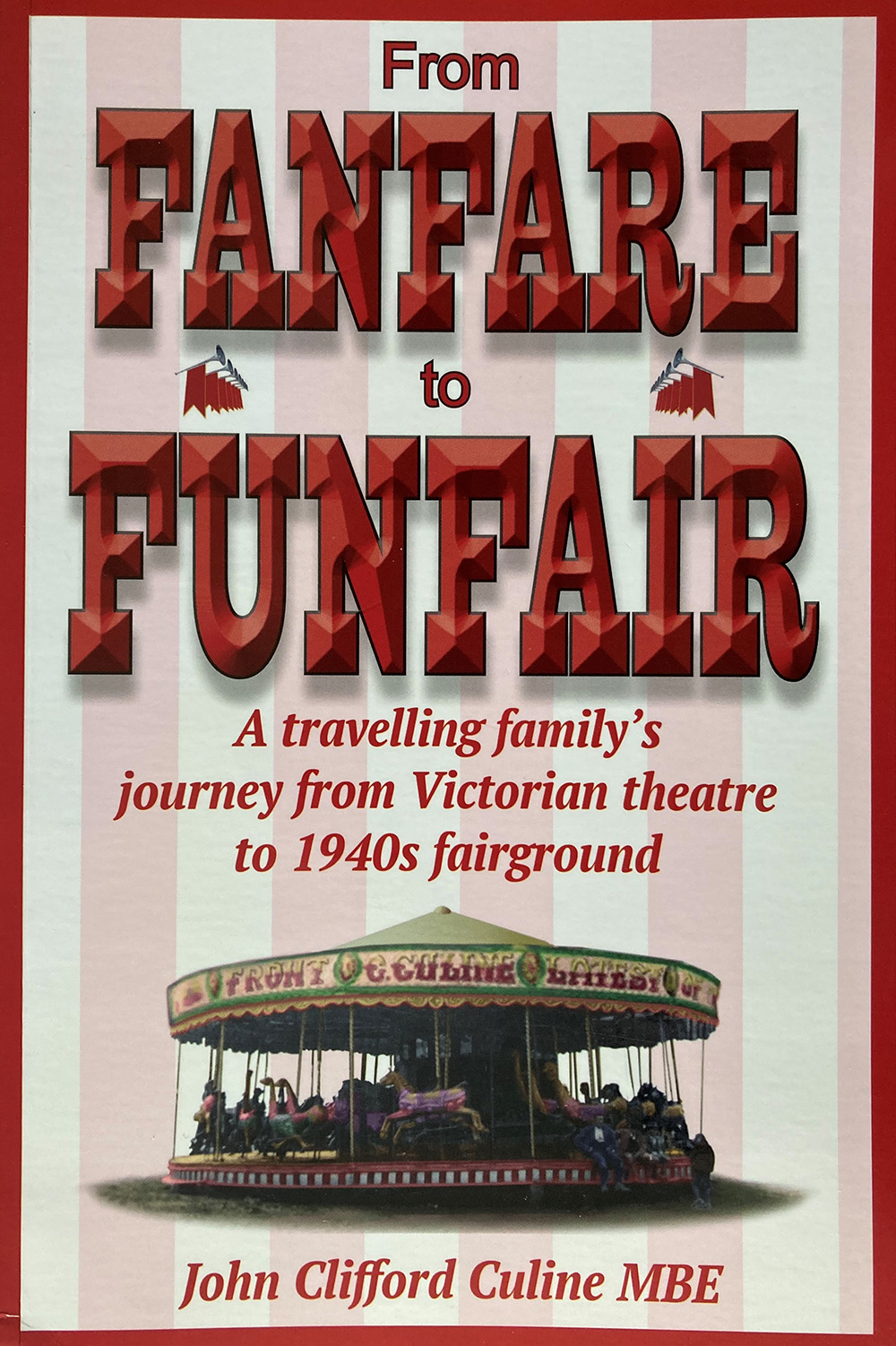

We’re not kings, we’re not queens, we’re the marvellous Culines said a Victorian Poster, a motto used by the family when they embarked on their life in the circus and fairground. A life that would encompass joy, sorrow, love, tragedy, and some incredible feats of showmanship. ‘From Fanfare to Funfare’ a book by John Clifford Culine MBE £14.50 is available from https://worldsfair.co.uk (National Fairground and Circus Archive) and when you look at the fairground pictures by Norman Cornish - every picture tells a story.

Newcastle and the role of galleries

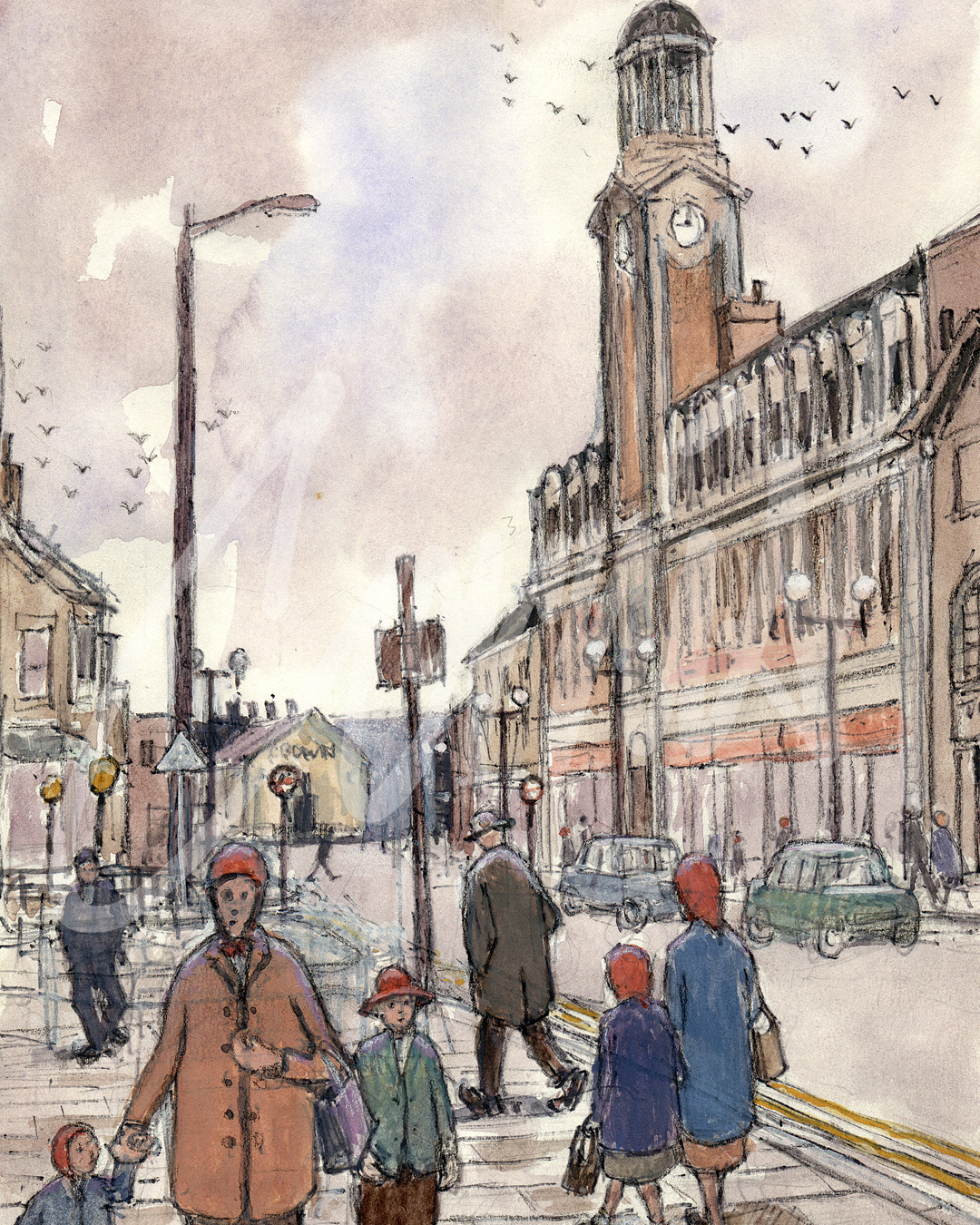

During the 50s and 60s the content of Cornish’s creative output was dominated by the subjects in his immediate surroundings; the industrial landscapes, the journeys to and from work, the pubs in Spennymoor, street scenes, observations of local characters and his wonderful record of the cultural landscape. He also exhibited alongside the work of other regional and national artists via the exhibitions at leading galleries in the North of England such as; the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle, The Shipley Art Gallery in Gateshead, Tullie House in Carlisle and The Stone Gallery in Newcastle. All of his solo exhibitions at the Stone Gallery were very popular with both admirers of his work and collectors. Buyers included the Prime Minister Ted Heath, and other artists including LS Lowry and John Peace. Over time the owners of the gallery, Mick and Tilly Marshall, also acted as ‘agents’ for Sir William Mc Taggart, Cumbrian artist Sheila Fell and LS Lowry.

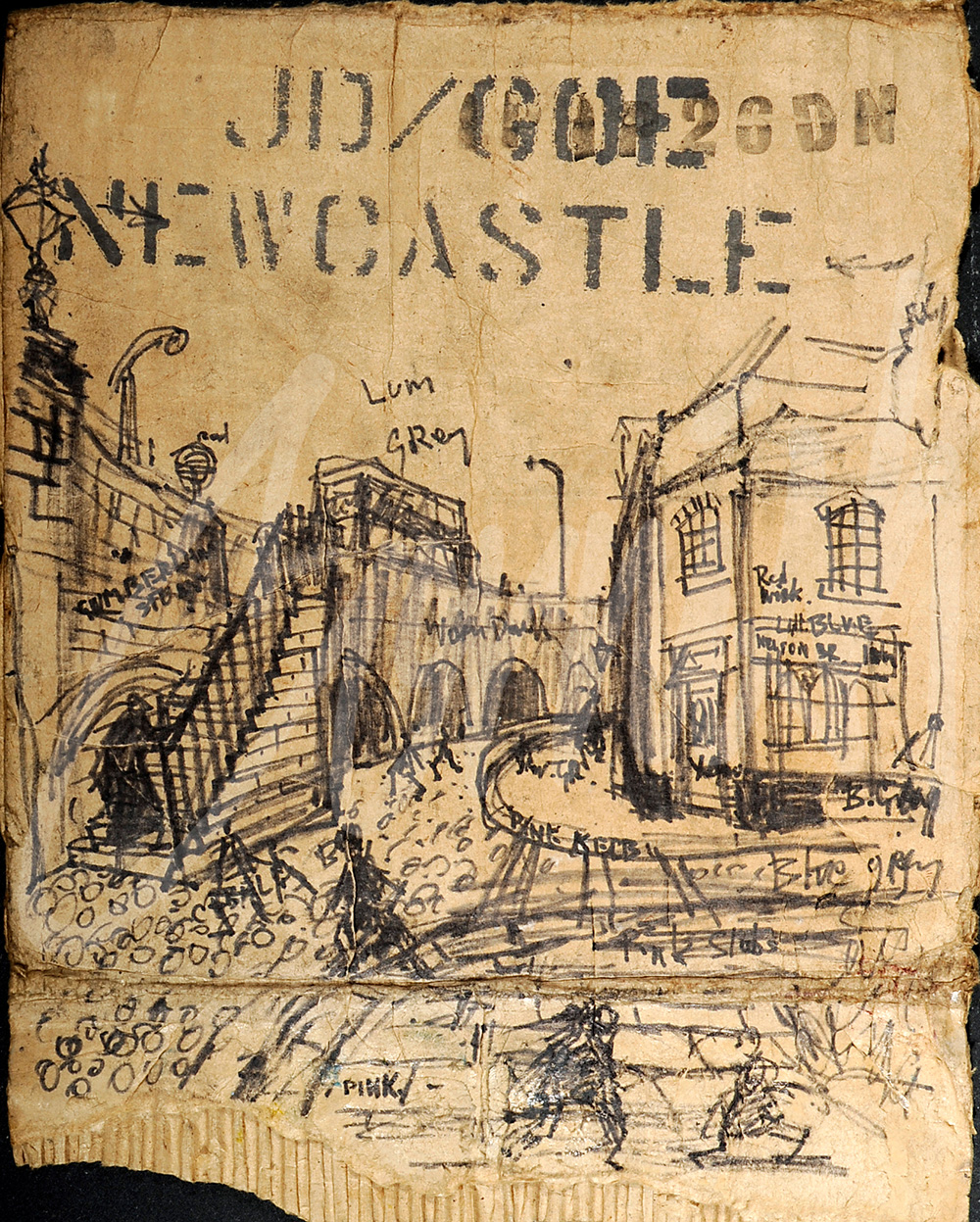

As a frequent visitor to Newcastle it was inevitable that the sights and sounds of Tyneside would begin to exert some influence on his choice of subject material. Uwilling to drive or own a car his journey to Newcastle began at the bus stop at the end of Bishops’s Close Street where the OK bus stopped on its journey from Bishop Auckland, and continued to Marlborough Crescent bus station in Newcastle. Walking from the bus station to the Stone Gallery near the Haymarket provided new city- based subjects that were irresistible to Cornish as he wandered through the city, pausing only to take out his sketch book, pen, and occasionally improvising on whatever surface was closest to hand, including a sheet of old cardboard !

His detailed sketch of All Saints church contrasts vividly with the group of men ‘hanging about’ the fence and steps near St Nicholas cathedral. All Saints church is also viewed from a different angle from under the Tyne Bridge and the drawing of Eldon Square, pre-shopping centre, must have been a magnet for his attention, dominated by people and pigeons!

Cornish’s association with Newcastle, and in particular with the owners of the Stone Gallery, began in 1959 and continued until it reached an abrupt end in 1980 after a disagreement. He continued to work for the next eight years in his studio at Whitworth Terrace in Spennymoor but without an agent or attachment to a gallery. In 1988, at a function in Newcastle he met the mayor, Theresa Russell, who arranged an introduction to the curator of the Polytechnic Gallery as it was known at the time, and which later became the University of Northumbria Gallery where he enjoyed a relationship for the next 29 years until the gallery closed in 2016.

Cornish always said how important it was to be associated with a reputable gallery to promote an artist’s work and the Norman Cornish estate is now represented by Castlegate House Gallery in Cockermouth to forge a new era under the direction of Steve and Christine Swallow www.castlegatehouse.co.uk In 2021 the gallery was included in the top ten commercial galleries to visit in England as identified by The Times newspaper.

The High Street

The Spennymoor High Street has been a prominent feature of the town since the original development in 1864 when it was surrounded by collieries, furnaces, and coke ovens. The original Town Hall situated on the High Street opened in 1870.

Norman Cornish was born in Oxford Street adjacent to the High Street and opposite the Town Hall. He ‘grew up’ in Bishop’s Close Street a short distance from the High Street where along with Sarah he returned to Bishops Close Street in 1953. The relocation of the family home to Whitworth Terrace in 1967 meant that they were often going ‘down the street’ or ‘up the street,’ which were popular expressions in Spennymoor.

The current Town Hall was built between 1913 and 1915 with a market hall and shops on the ground floor. A public hall, council chamber and offices were on the first floor and later re-located to the ground floor to improve public access. Following a determined effort by Bob Abley to create an art gallery the first exhibition was held in 2011 entitled, The Art of Spennymoor Settlement, featuring works by Norman Cornish, Bert Dees, Bob Heslop, Tom McGuinness and Jack Roach.

The Spennymoor railway station, opened in 1845, was located near the roundabout at the top of the High Street, but it was closed to passengers in 1952 and completely closed in 1966.

The Grand Electric Hall (Wetherspoons) was originally the Arcadia cinema with 1,000 seats and a market hall. Sadly it was destroyed by a fire in 1929. The cinema was re-built and by 1931 had a new ‘Western Electric’ sound system, stage and café but it closed again in 1970. Later, the building was converted to a Bingo hall and re-opened in March 2013 by Wetherspoons.

All of these changes to buildings are so typical of similar changes experienced in towns and villages throughout the region and beyond. The High Street was like a central spine of the town which provided so many opportunities for Cornish to observe and record in his work the people and places which are synonymous with his artistic output. In his own words:

“Spennymoor has all that a painter needs to depict humanity.”

Visitors are able to follow in his footsteps by walking around the Norman Cornish Trail which starts and finishes at the Spennymoor Town Hall – located on the High Street. Details may be found by visiting www.normancornish.com/trail

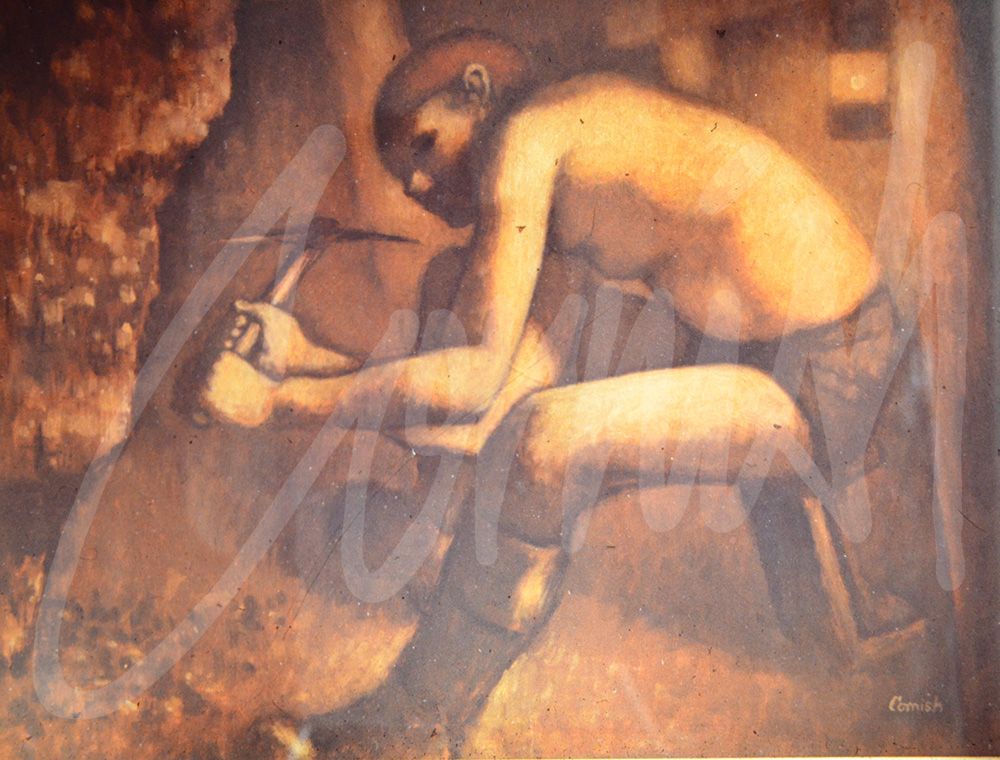

Industrial Gladiators:

Future generations may one day ask, ”what did coal mines look like and what did the men do underground?” The paintings of Norman Cornish have provided an honest and authentic illustration of life in the great pit villages and mining communities in County Durham. In his own words:

“ I didn’t think consciously about creating something that people would be able to look back on and say, ‘that’s what it was like’ but it must have been in the back of my mind: the thought that one day, someone could look back at my paintings and feel what it was like.”

The choice of the word feel is so incisive when viewing paintings by Cornish, whether it is the pit road, working underground, a pub scene or other observations of people and places. “If a painting carries nothing of life experiences it is sheer decoration.”

Cornish was ‘set on’ at Dean and Chapter Colliery to start on Boxing Day 1933 as a ‘datal lad.’ When he was 18 he was offered work as a ‘putter’ which meant a slight increase in his wages but the work was hard and dangerous. The job entailed conveying the full tubs of coal on rails from the coal face to the bottom of the pit shaft and leading empty tubs back to the coal face.

Eventually it became his turn to be a coal hewer; work which was done by hand, using a pick, shovel and drill along with a hammer and saw for installing props. Pay was related to the amount of coal produced and the work space was illuminated with the aid of an oil lamp – about one candle power!

At Dean and Chapter Colliery in 1935 there were 2,135 men working underground and 538 above ground and by 1937 the workforce was producing 3,000 tons of coal per day – a third of it machine mined and the rest hand hewn. The Dean and Chapter Colliery was referred to as ‘the Butcher’s Shop’ and on average there were six fatalities per year and minor injuries more frequently. The challenge for Cornish working underground was his desire to record what was happening around him whilst trying to continue the physically demanding work. The owners of the mines had no time for artists and aesthetics and it is simply remarkable that he was able to continue his output as an artist under such difficult conditions that he described as: ‘The dangers of gas, stone fall, the darkness and restricted space were all to shape these men into industrial gladiators.’

More Articles...

- Jackie Broomfield

- Royal Jubilees

- Behind the Bar

- The Creative Process Part 4 The Crowded Bar

- The Creative Process Part 3 The Busy Bar

- A Good Drying Day:

- John Peace Exhibition: Tyne and Tide - South Shields Museum and Art Gallery

- Convicts and Slaves: Symbolism

- The Art of Drawing

- The Adventure Alternative: