Latest News

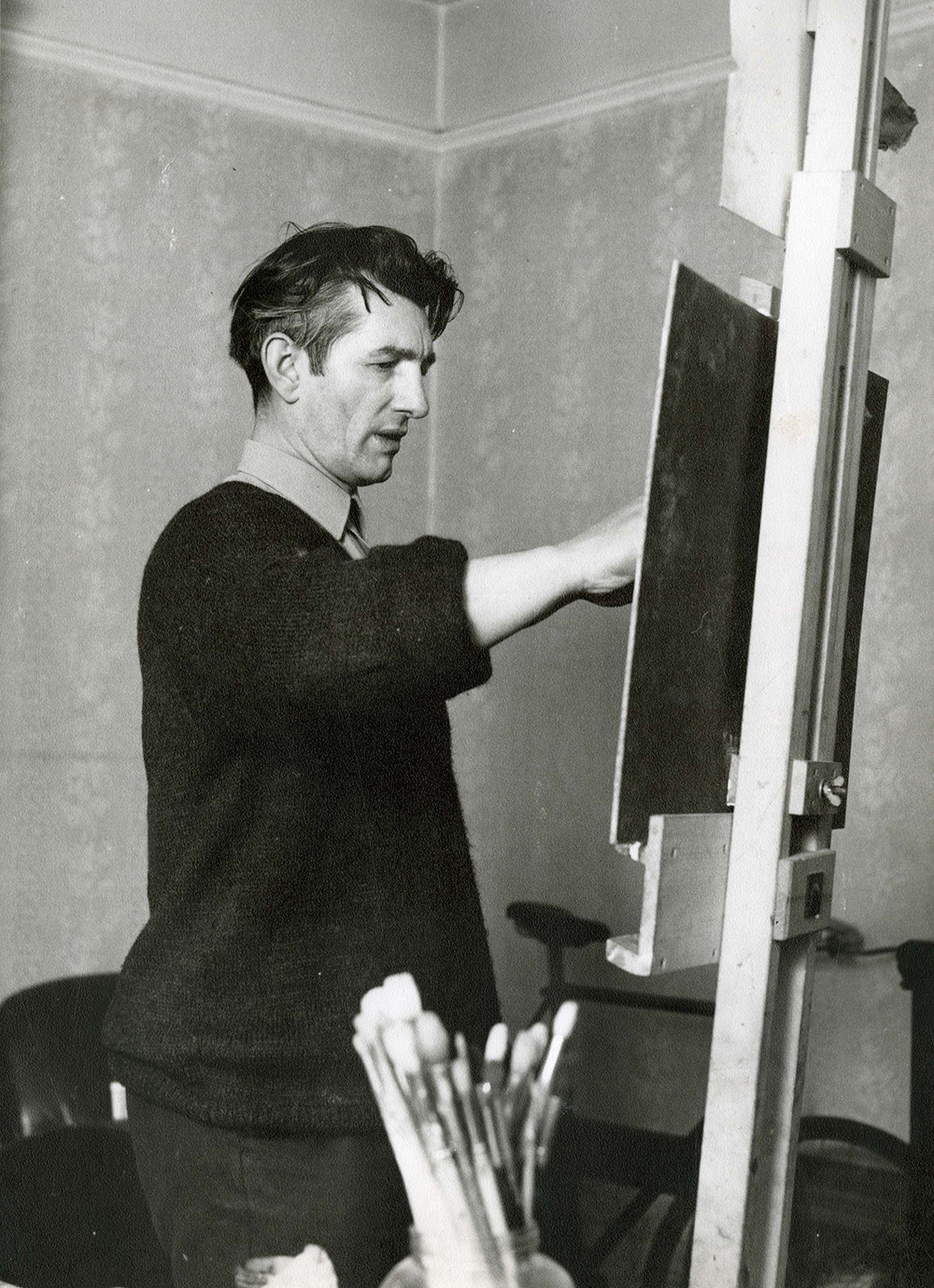

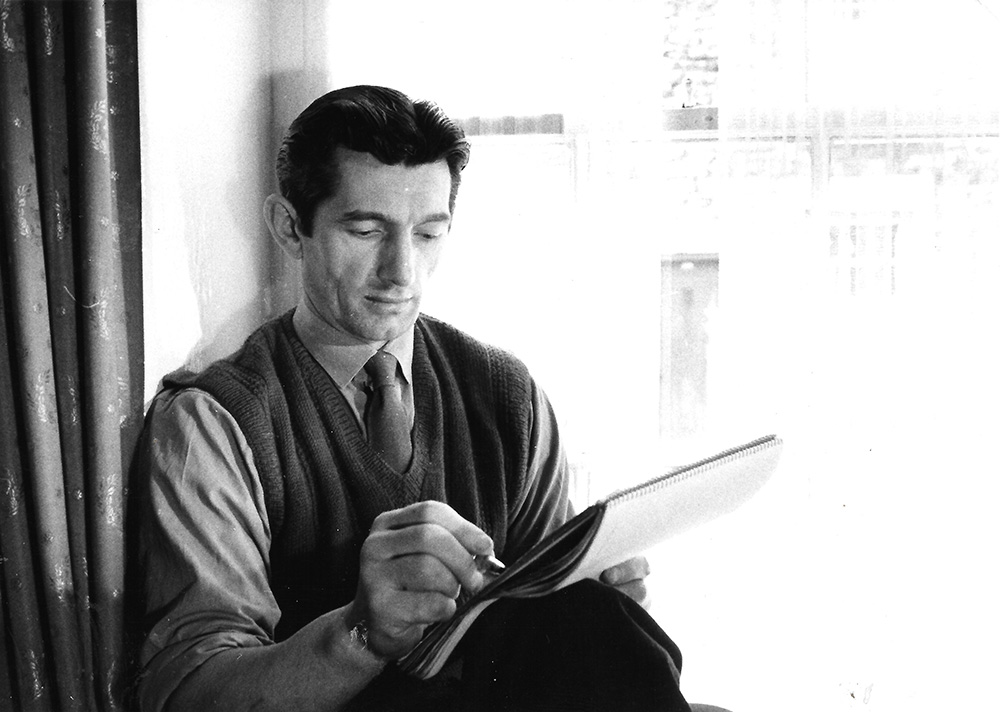

A Bedroom Studio

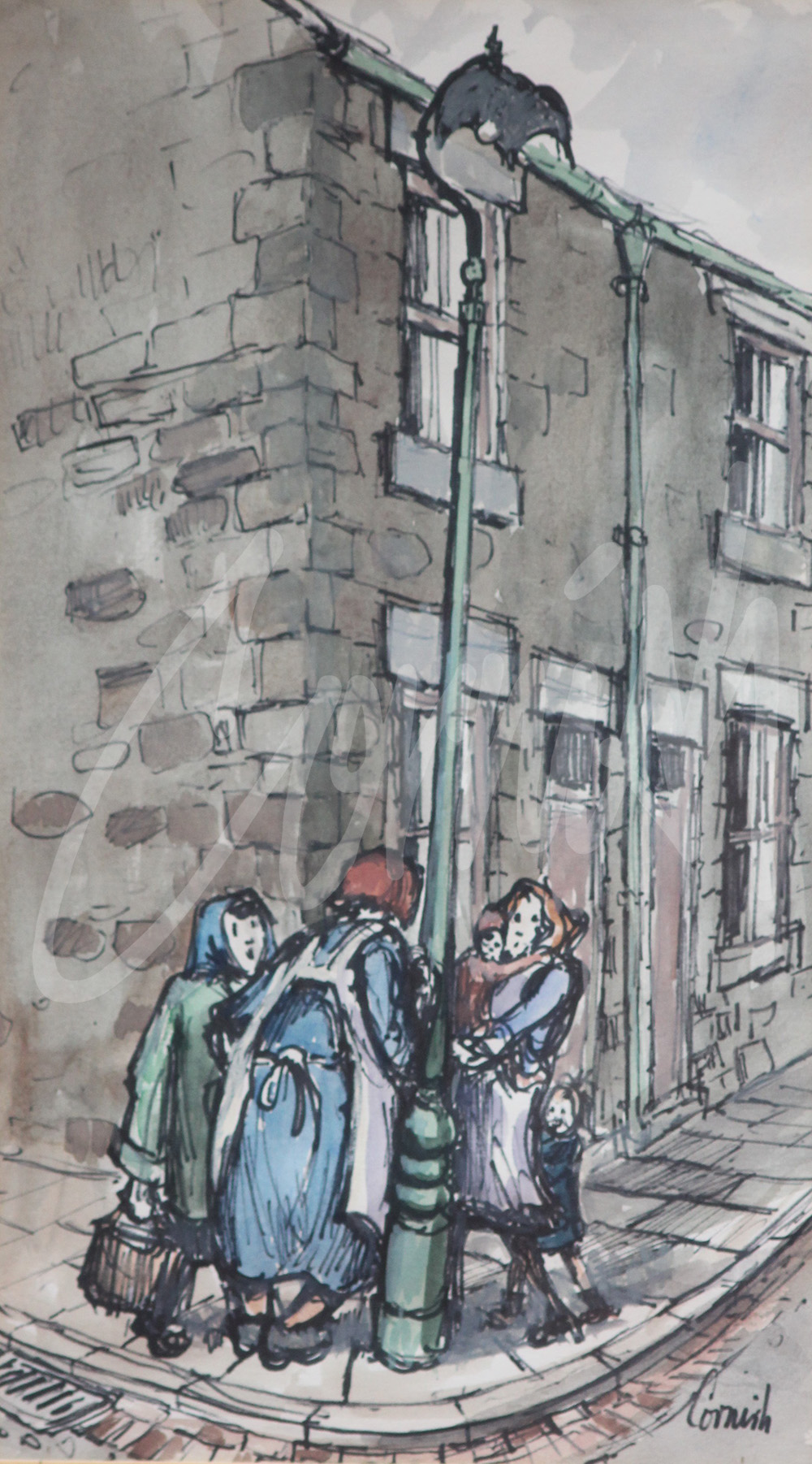

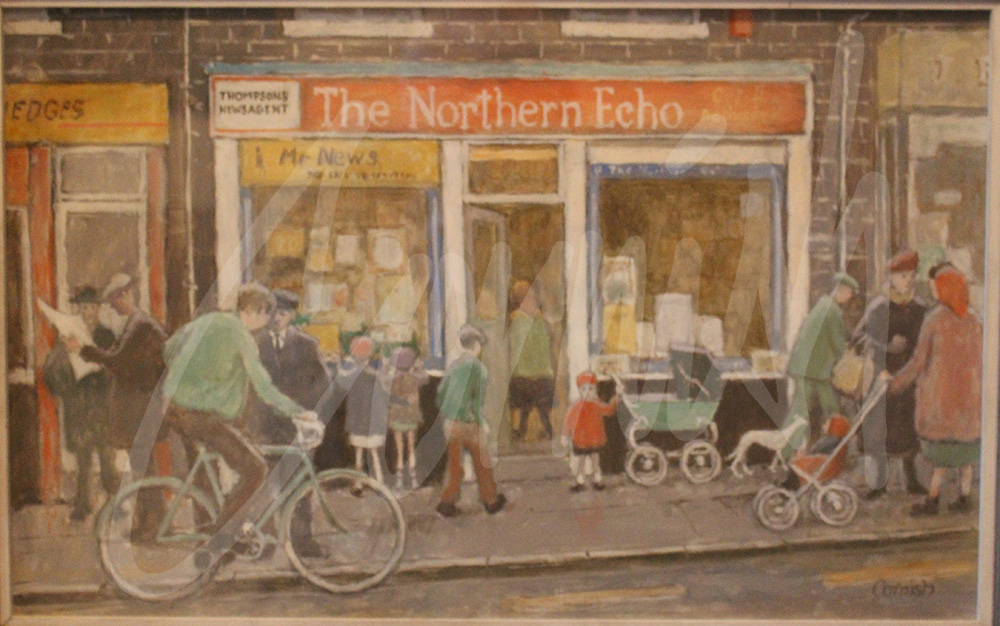

There are few people in the North East who would fail to instantly recognise the work of Norman Cornish. His evocative paintings and drawings provide an unrivalled social record as a Chronicler of an important era in English history. His observations of people and places are a window into a world which no longer exists outside but which Norman has immortalised for us all with its struggle, its beauty, its squalor and its dignity.

Cornish was born in 1919 in Spennymoor, County Durham, in a house with no bathroom or inside toilet, where he shared a room with his five brothers and one sister. He described living conditions as ‘primitive’ and he contracted diphtheria when seven years old. The only reading material at home was an American detective comic.

His journey from miner to professional artist, is a story of determination and resilience to overcome hardship and prejudice.

He joined the Spennymoor Settlement Sketching club aged 15 in 1934 after initially being turned away for being too young! The impact of the advice, activities and experience of being a member is well documented. His personal circumstances were more than challenging but he was determined to succeed despite the enormous barriers encountered daily.

Cornish’s modest income as a miner was a constraint upon the acquisition of materials and a further dilemma existed between his interest in art and aesthetics when faced with the hazards he found when working and surviving underground. ‘Treated like slaves, and spoken to like convicts,’ such was the reality of being a miner, which also had a significant impact upon his work and interpretation of his subjects. How on earth did he cope ?

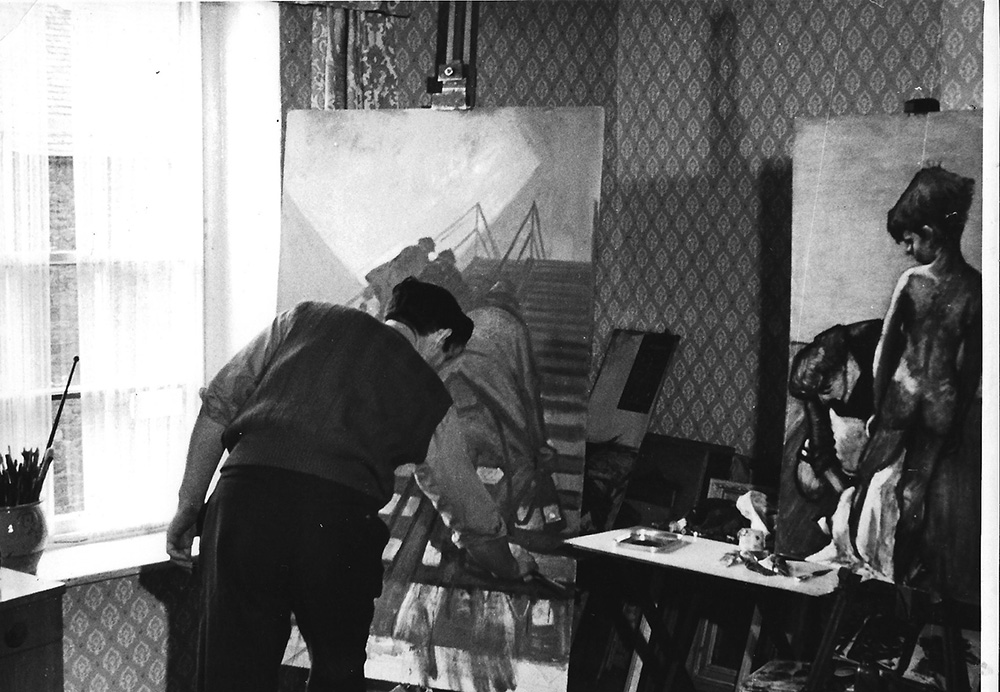

His first attempt at an oil painting ‘My Sister Ella’ (1940) was completed over three sessions in his parent’s bedroom. When Norman and Sarah moved to 33 Bishops Close Street in 1954 the only solution to create a space to work in was to move his easel and materials into their bedroom. Sarah was very tolerant and supportive under the circumstances. There were materials, canvas, sketchbooks, frames, ink for his Flo-master pens, boards, incomplete paintings, pastels and the smell of oil paints and Turps for cleaning brushes. The smell was often overpowering. When he was commissioned to paint the Mural one of the preliminary versions was scaled to 300cm and placed from the bedroom window sill to the top of the stairs via an open door. To climb into bed Sarah sometimes had to crawl over or under the bed!

The family moved to Whitworth Terrace in 1967 where there was sufficient space to convert a former Methodist Minister’s office into a studio, and this is what is displayed at Spennymoor Town Hall. The bedroom studio from Bishops Close Street has been re-created at Beamish Museum and it is an authentic replica but without the smell of oil paints and other materials. The paintings scattered in the corner of the room are reproductions of the original works.

Despite the obstacles to success a rare talent emerged in the post war years. He developed a burgeoning national reputation which placed further pressure on his future direction. Circumstances, and support from Sarah, enabled his progression to become a professional artist in 1966, a journey which was to span a further forty six years until he finally stopped working in 2012. He worked for more years as a professional artist than he did as a miner underground, a fact often overlooked. In the 21st century it is not uncommon to find talented young people working from their bedroom on their journey to future success.

Realism to Abstraction

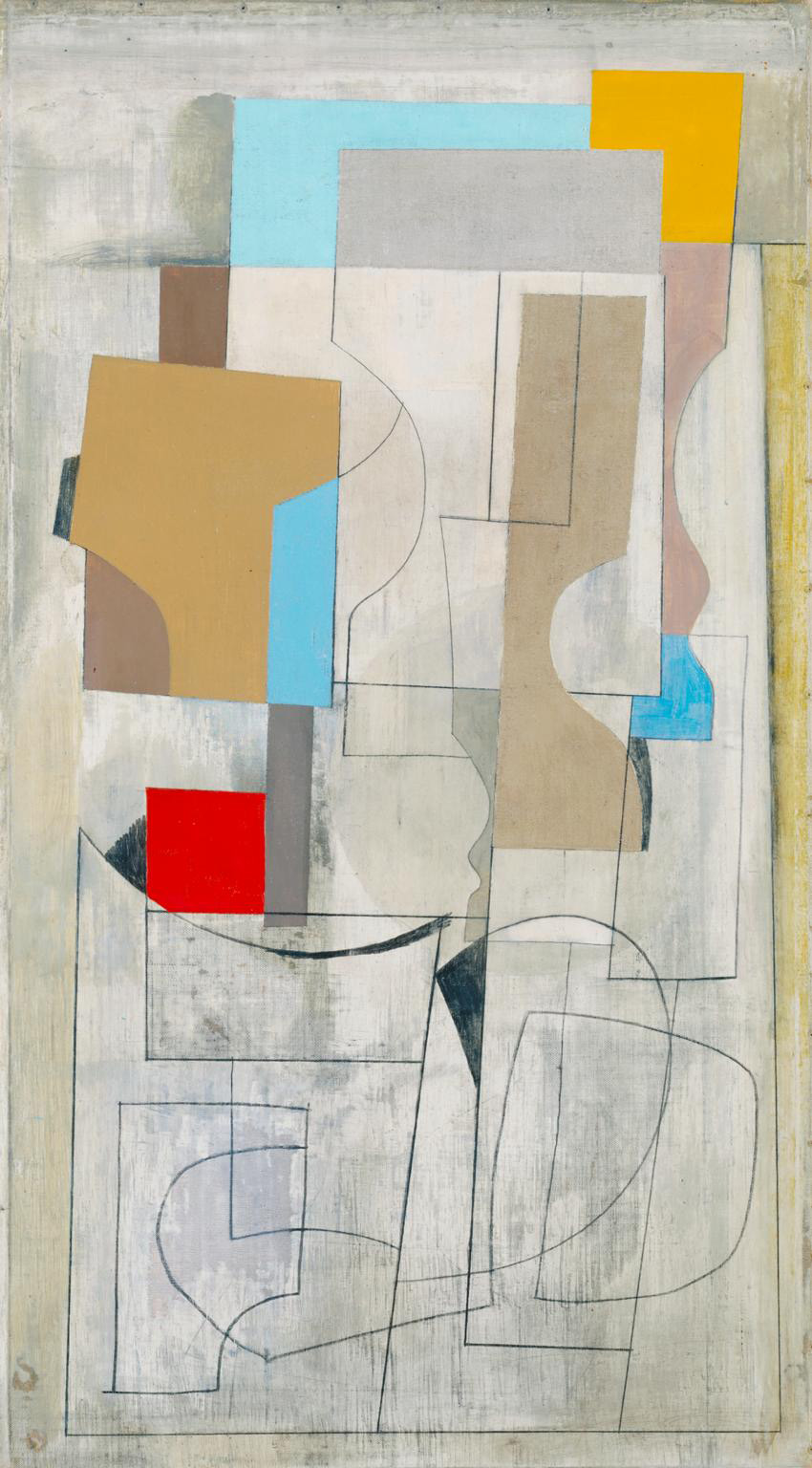

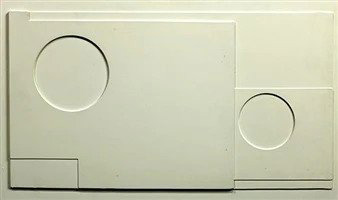

The recent return of the BBC programme ‘Fake or Fortune,’ episode 1, featured a recently discovered painting on the bedroom wall of a house in Surrey. The decision of the ‘experts’ revealed that it was most probably a collaborative piece by Ben Nicholson and Fred Murray. A number of geometric shapes and bright colours which were evident in Nicholson’s other works were depicted in this painting.

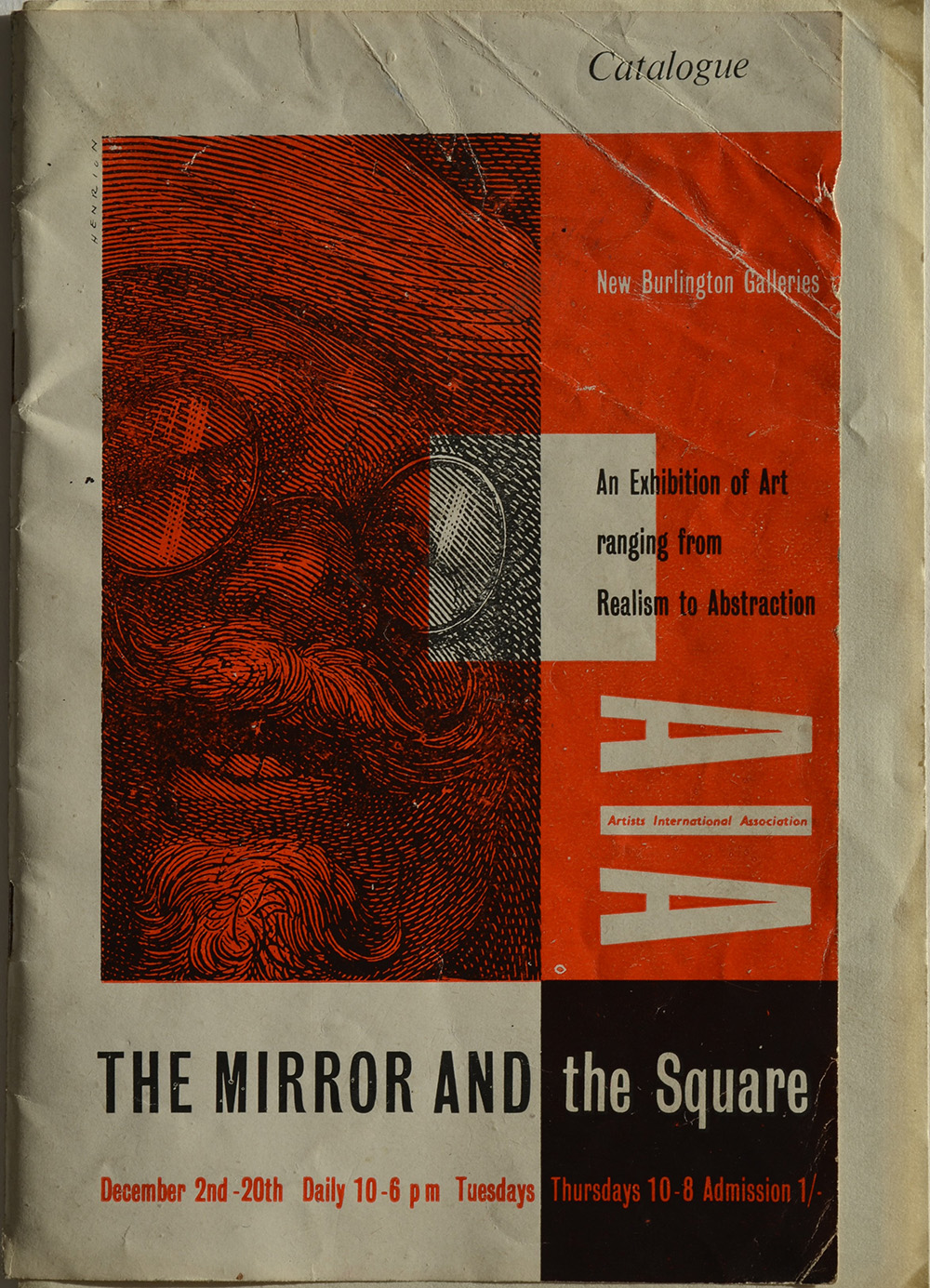

Paintings by Cornish and Nicholson actually featured together in two different exhibitions during the 1950s and 60s. The first occasion was in 1952 at ‘The New Barrington Galleries’ in London: ‘The Mirror and The Square- Realism to Abstraction.’ Other artists included LS Lowry, Stanley Spencer, Victor Pasmore, Graham Sutherland and Barbara Hepworth. Cornish exhibited ‘Miners Going in Bye’ and Nicholson exhibited ‘White Relief.’

The post- war era was a period of rapid social change and art movements such as Cubism, Fauvism and Surrealism to name but a few, continued to evolve. Cubism was an early 20th Century style and movement in which perspective with a single viewpoint was abandoned and use was made of simple geometric shapes, interlocking planes and later collage. Cornish was well aware of these developments but declined to follow the popular trends. However, any aspiring artist in art school unwilling to follow ‘the trend’ was often ostracised by lecturers. This was the experience of John Peace, a contemporary of Cornish. Meanwhile, Cornish and Lowry continued to develop their own distinctive styles based around social realism, and without veering towards abstraction.

The Stone Gallery Mixed exhibition in1967 included ‘The Cup’ by Ben Nicholson and ‘The Gantry’ by Cornish, an earlier version of which was purchased by Lowry in 1964.The journey by Cornish from miner to professional artist was a story of great determination and resilience to overcome hardship and prejudice. Cornish was denied a place at ‘The Slade School of Art’ in London due to the outbreak of World War 2 as mining was a reserved occupation. Nicholson, however, trained as an artist at ‘The Slade School of Art,’ 1910-11, although he apparently spent more time during his year at Slade playing billiards than painting or drawing. He later claimed that the changing relationship of the coloured balls were of more appeal to his aesthetic sense. Nicholson was married three times and produced six children. His second wife was the artist Barbara Hepworth.

During the 50s and 60s Cornish’s reputation continued to grow, not only as an artist of considerable talent but also as an authority on art history, aesthetics, literature, music and contemporary matters. He was often invited to TV and radio discussions, along with other eminent practitioners, and occasionally as a guest speaker at conferences and weekend workshops. One such event was held at Ormesby Hall on July 4th 1968 and was organised by the ‘Federation of Northern Arts,’ later to become Northern Arts and Arts Council North. He always conducted himself with great dignity and his lecture notes have recently been transcribed. His final statement to the invited audience is presented here for the first time and reveals his thoughts about the difference between decoration, illustration and art in a powerful summary.

‘If a painting carries nothing derived from life experiences it is sheer decoration. If on the other hand it merely copies life without translating such experiences into forms proper to its medium it is nothing more than illustration paler than life, and without the impact or the new experience implicit in any work to which we give the name of art.’

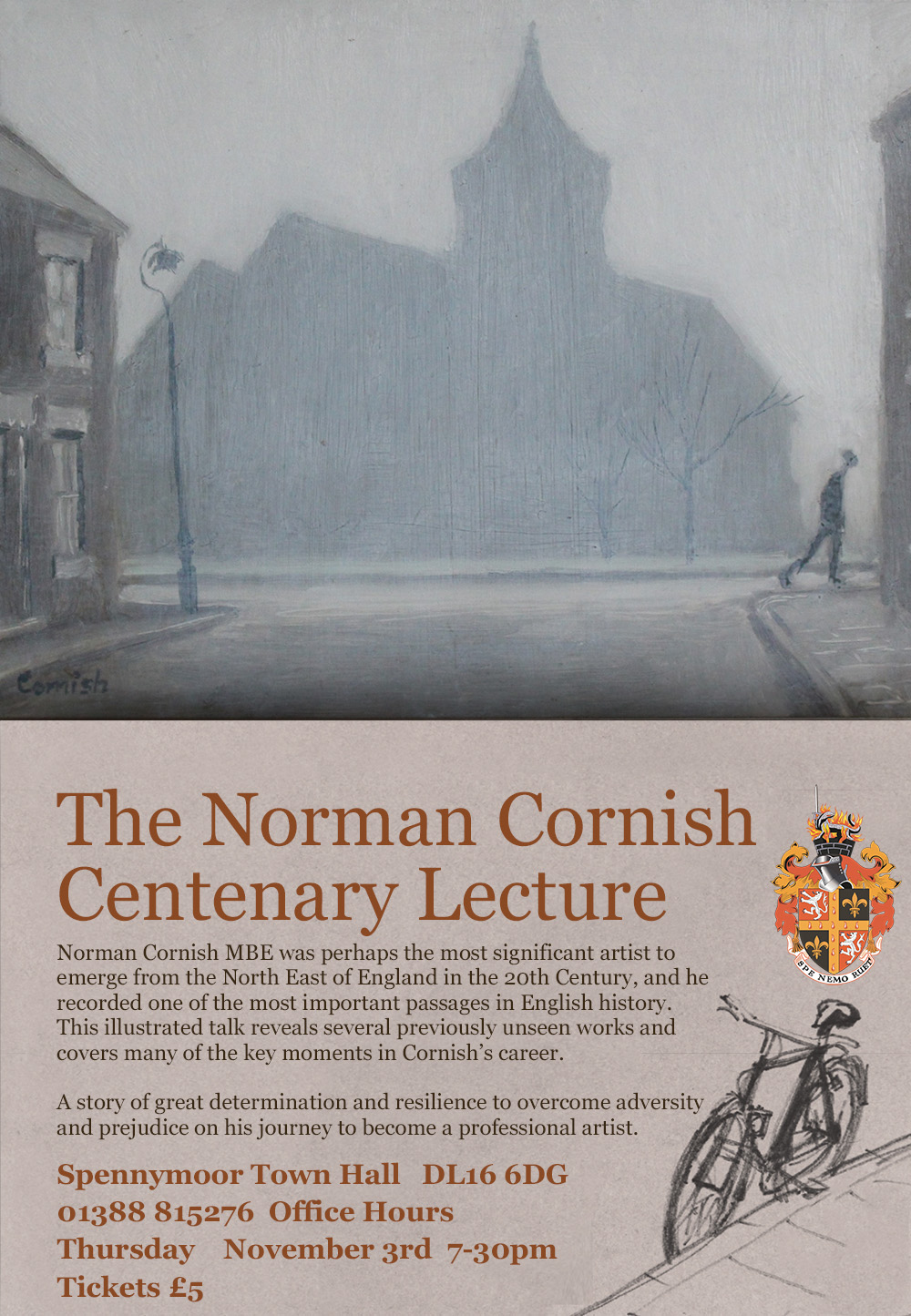

‘Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Centenary’ lecture 1919-2019

Spennymoor Town Hall 7-30pm Thursday November 3rd 2022 7-30pm

An illustrated talk by Norman Cornish’s son – in law Mike Thornton

Tickets £ 5 From Spennymoor Town Hall Reception and also available via telephone in normal office hours Monday to Friday - 01388 815276

Norman Cornish MBE was perhaps the most significant artist to emerge from the North East of England in the 20th Century, and he recorded one of the most important passages in English history. Revealing predominantly unseen works, the talk covers many of the key moments in Cornish’s career including commissions such as The Durham Miners’ Gala Mural in 1962, Cornish in Paris in 1967 and two commissions for The Port of Tyne Authority in 1982. The talk also includes images of life in his family home from the 50s and 60s in Spennymoor, which has been recreated as part of the 1950s town at Beamish Museum.

It is a story of great determination and resilience to overcome adversity and prejudice on his journey to become a professional artist.

Please arrive early. Doors open from 7pm.

The Bob Abley Gallery including the current ‘Coming Home’ exhibition and Norman Cornish studio will be open between 6pm and 9-30pm

Free parking behind the Spennymoor Town Hall

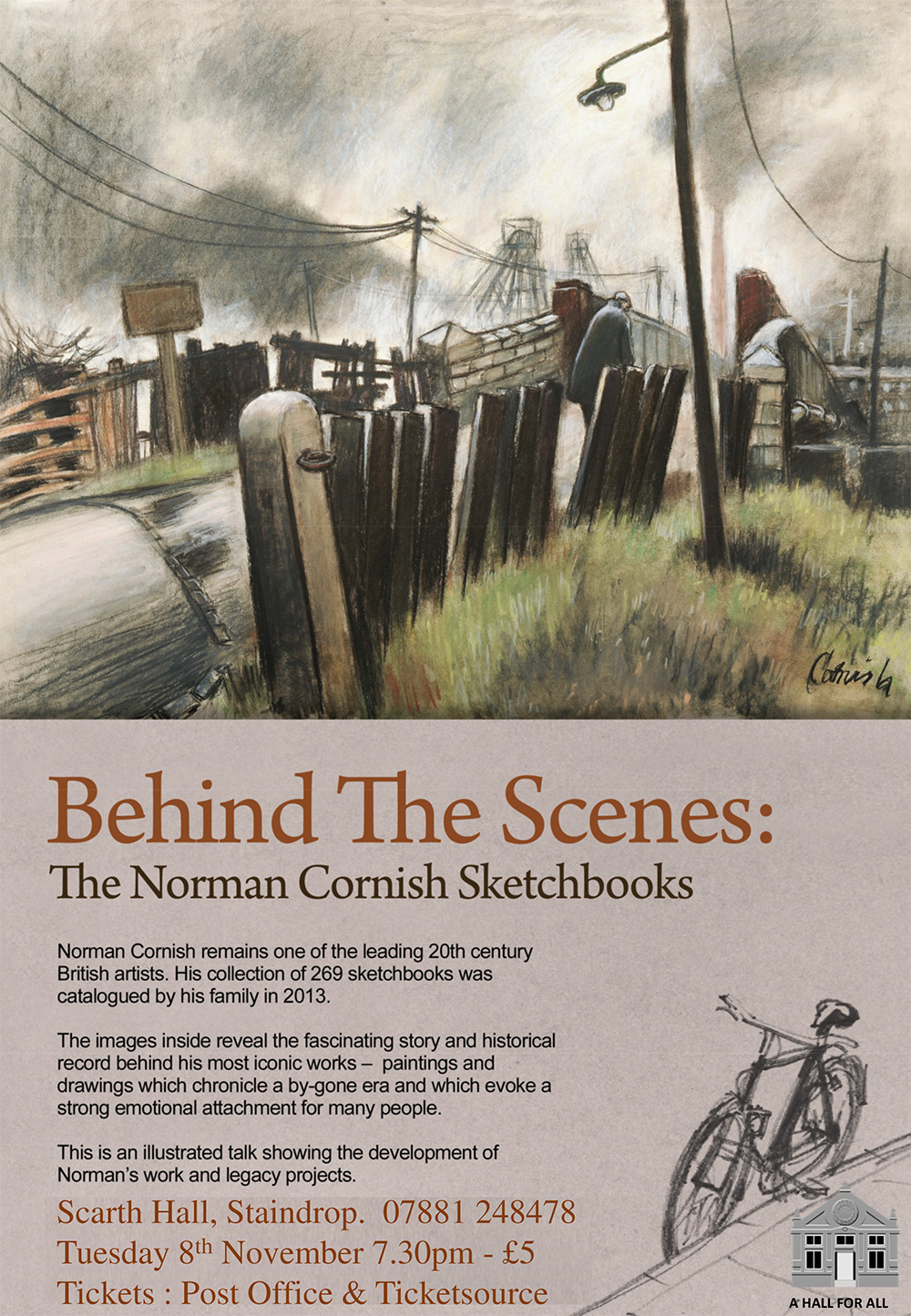

Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks at Scarth Hall

Scarth Hall, Staindrop, County Durham November 8th 7-30pm

An illustrated talk by Norman Cornish’s son – in law Mike Thornton

Tickets £ 5 available via: www.scarthhall.co.uk or ticketsource.co.uk

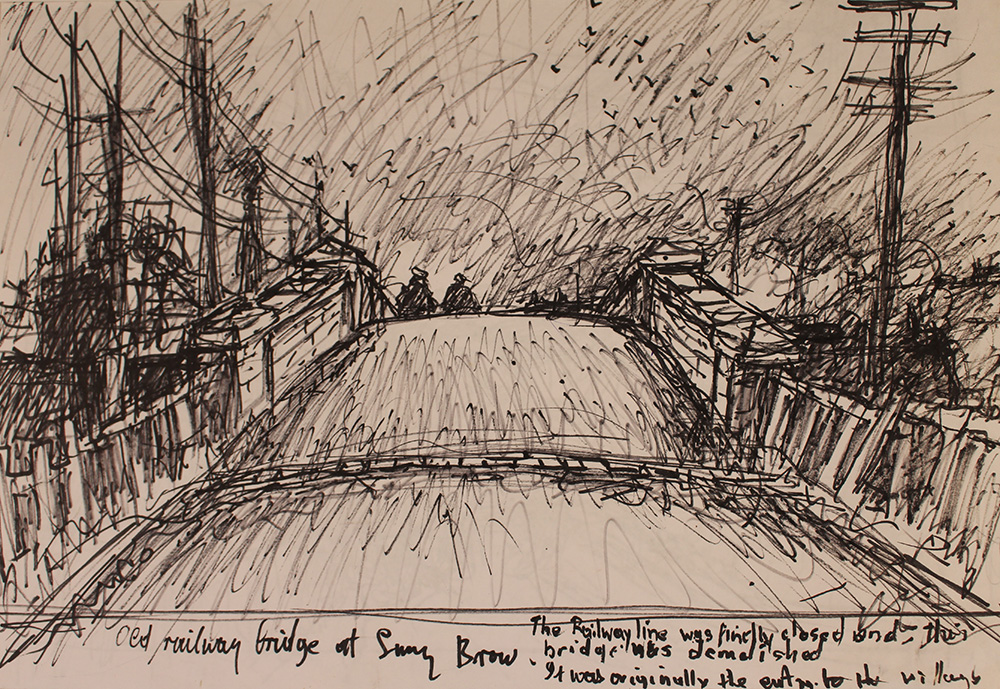

Norman Cornish MBE was perhaps the most significant artist to emerge from the North East of England in the 20th Century, and he recorded one of the most important passages in English history. Prior to his death in 2014 he requested that his 269 sketchbooks ‘should be available to the public to view, to teach people to look at things.'

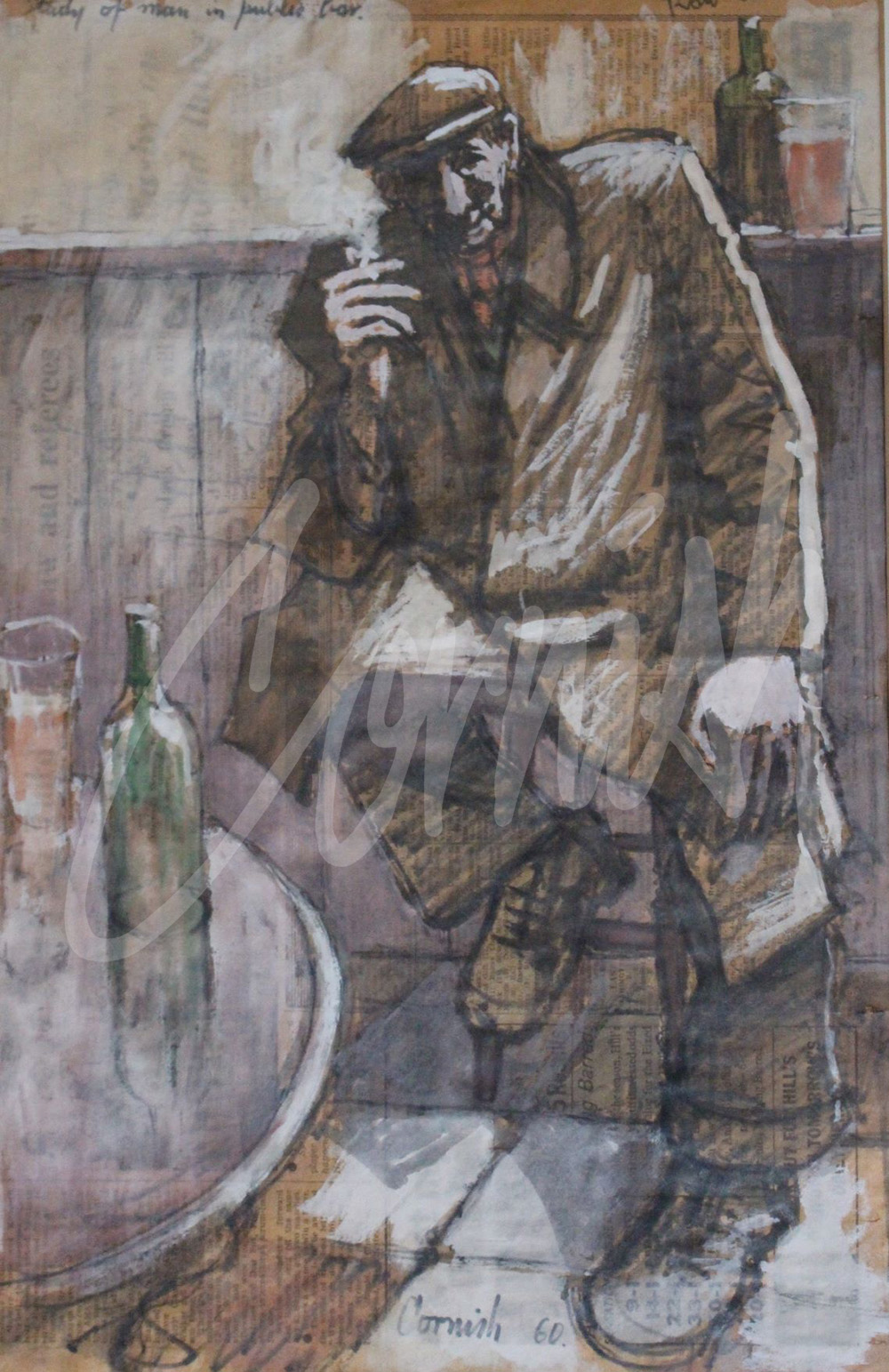

Cornish recorded a fascinating portrait of life in County Durham and his sketches reveal the creative process and historical record behind his iconic paintings of a bye-gone era. He portrays human relationships - the men engrossed in conversation at the bar, the women gossiping on the doorstep, and the children playing in the snow. Cornish was rarely without a sketchbook, using it to prepare for the scenes he painted. His sketches illustrate his obsessive commitment to recording life around him and were done occasionally on scraps of newspaper or whatever ‘was to hand.'

This illustrated talk highlights some of his most iconic works and also covers a selection of the legacy projects.

Please arrive early. Doors and bar open from 7pm.

The Unseen Works - ‘Did you know?’

The programme of lectures about the life and work of Norman Cornish commenced about five years ago following the launch of ‘Behind The Scenes: The Norman Cornish Sketchbooks.’ In 2019 the series of lectures continued around the theme of ‘The Norman Cornish Centenary Lecture’ and the public appetite for these illustrated talks remains as strong as ever.

There are two distinct settings for lectures and some take place for the members of societies and formal groups such as Local History Societies, U3A, Arts Groups, Women’s Institutes, Rotary Clubs, PROBUS and Friends of …… etc. These events support the benefit of membership of a wide range of community groups. In addition many Primary School groups in County Durham have also enjoyed the illustrated talks delivered by Dorothy and John Cornish as part of their curriculum experience.

Public lectures are slightly different in that they are available for any member of the public and a nominal ticket fee is charged which also helps the organisers plan for the anticipated numbers arriving. Public lectures have also taken place at Art Galleries, Arts Centres, Town Halls, Book Festivals, The Lit & Phil and Redhills .

One of the unintended outcomes at all of these venues has been at the end of lectures when members of the public make contact to announce that they own a ‘Cornish,’ or know someone who does own a picture. A conversation often starts with ‘Did you know?’ and without exception a whole range of fascinating anecdotes have been disclosed regarding Cornish, his work, his life, and historical relationships with other artists such as Sheila Fell, LS Lowry, John Peace and Ned Owen .

The pictures featured today were previously unseen and purchased during the Stone Gallery era in Newcastle. Details have been recorded for the ‘back catalogue’ in preparation at Northumbria University.

Two public lectures are planned for November and details will be published during the next two weeks. Hopefully some further conversations will ensue after the opening line, ‘Did you know?’ and perhaps some previously unseen works by Cornish may also emerge for the public benefit.